Lygia Pape’s remarkable show at the Met Breuer underscores this venue’s commitment to a program showcasing artists who are mostly outside the purview of conventional American interest. Recently, the Met Breuer put up the outstanding overview of Arte Povera artist Marisa Merz, wife of the major sculptor Mario Merz. As the show made clear, Marisa Merz is an important artist in her own right. In the current show of Lygia Pape, we meet a forceful practitioner of modernism, more specifically the art of Neo-Concretism, which emphasized art’s interaction with life, moving away from the narrower formalism of Concretism, its precursor. This short-lived movement, from the late 1950s to 1961, ultimately derived from Russian Constructivism, but more accurately was a spin-off from the more conservative Concretist artists in Sao Paulo. The artists practicing Neo-Concretism produced art that also looked closely at the modernists working far away from Brazil and translated it into something far more improvisatory, and interactive than the work that influenced it, even as it retained a formal orientation toward geometric abstraction. The three major artists in this movement, called Grupo Frente, were Lygia Clark, Helio Oiticica, and Pape herself. Pape’s work preceding this movement, art made mostly in the middle 1950s, presents schematic, abstract designs that reflected the influence of modernism outside her culture. These smallish works are striking for their intelligent exploration of advances known internationally. Most of the compositions are notably simple—squares and straight lines arranged in awkward relation to each other.

These works feel like attempts to establish a vocabulary and style that would re-introduce geometric abstraction to Brazil’s art community on its own terms. Certainly, as time went on, Pape would not only continue in this vein but also, during the dictatorial rule of the 1960s (and beyond) in Brazil, confront governmental excess. In addition, Pape’s originality would lead her in the direction of viewer participation, for example, the huge cloth sculpture, a kind of garment with multiple openings for participants to push their heads through, thereby enabling a physically unified community. At the same time, it was an assertion of community in the face of a repressive government. This moment in Brazil was remarkably exciting and not so well known until recently here. One of the big mistakes made in the American art culture is its myopia in regard to transnational accomplishments—often superficial attention is paid to the artists visiting New York from far away, but there is no real attempt to understanding the art on its own terms. (Most recently this happened with Mainland Chinese art in New York, which was enthusiastically embraced for roughly 15 years—from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s—before the artists from Beijing and Shanghai returned to China, disappearing from the scene.) More recently, perhaps because of a greater Latin American presence in New York, there has been an attempt by museums to rectify the neglect. But important artists like Pape, and Oiticica and Clark, are still indifferently received, although Pape’s show at the Met Breuer is a big step in the right direction.

The real question to be faced in looking at Pape’s confident and original re-visioning of art from historically dominant cultures is whether her work can stand on its own. As the show makes abundantly clear, Pape is a major artist in contact with the world art that was prominent at the time. It is important to remember that Brazil was hardly an artistic backwater at this time; instead, its best artists stand at the top of any world survey of the period. Unfortunately, and perhaps inevitably, their achievements have remained slightly obscure in the American landscape. But, as I have commented, things are changing. Unfortunately, because of the market, the New York art world continues to rehash Ab-Ex achievements that occurred decades ago Such an emphasis has made it difficult for foreign-born artists or minority artists to break in. This is a big mistake, for the future will have to acknowledge the increasing complexity of an art world that has already become vastly diverse. New York truly needs to show as many different kinds of art as possible—and to stop adulating the art of decades ago. This must be done in order to let the next generation contribute to the ongoing discussion. Pape’s show demonstrates the high standards of the artists working with Neo-Concretism, even as her art silently acknowledges the influence of cultures outside of her own. This is, of course, inevitable: When has art not made use of other cultures? The practice goes back way before Picasso’s appropriation of African art; cultural exchanges are being documented all the time, even in notably archaic periods. In fact, Neo-Concretism was swiftly followed by experimentation in conceptual art in Brazil—decades before the same impulse took place in New York!.

The kind of art Pape made early in her career demonstrates more than a small acquaintance of geometric abstraction. Such work carries with it very little cultural baggage except for the recent example of modernism, which championed the style. The work feels both rational and experimental at the same time. Indeed, one of the strengths of this show is its difference from the cloying excesses of Abstract Expressionism. Yet we remember at the same time that geometric abstraction shared part of the 20th-century art spectrum. The simplicity and regularity of the forms establish a narrow but striking idiom, in which the often similar forms are arranged and re-arranged for the sake of sequential interest. Several collages on cardboard, from the mid-1950s, work out a schematic organization that remains compelling some three generations after they were made. Study for “Relevo (Relief)” (1954-1956), a collage on cardboard, consists of a black square with a row of small white squares descending from left to right. Its straightforward composition is echoed in Study for “Pintura (Painting)” (1955), another collage on cardboard. Here a black square, angled on its side, is found above three red, diagonal stripes with a small red square beneath them. The latter work looks Constructivist, but we must remember the gap in time between the Russian innovations, brought about by the first artists to work with the language seen in Pape’s efforts, and the art of the Brazilians.

During the middle 1950s, Pape paid considerable attention to reliefs, painting with gouache and tempera on fiberboard on wood. These works are low reliefs, usually extending from the picture plane by a little more than two inches. Again the vocabulary of the works is simple, relying primarily on elements that are geometrically derived. In one Relevo (Relief) (1954-56), thin stripes of black and yellow rise from each of each of the four corners of the work, moving toward the middle of the relief but not touching. On the right edge, there is a long, slightly dark yellow line that extends down the length of the wooden surface. The cultural content is reduced to a minimum in this kind of work, which presupposes a sharp eye rather than a knowledge of culture for appreciation. Still, at this point, this kind of work has a history of its own, one stretching back to the early twentieth century, when it had a decidedly political bias. Nothing can be discussed completely out of context, although this kind of work was a genuine innovation for Pape and her colleagues at the time in Brazil. In the mid to late 1950s, the “Tesselares” appeared—a group of woodcuts on paper. These designs were not so hard edged, expressing instead to an organic vocabulary, which softened the effect of the art’s elements. Is it possible to move away from a purely formal description of abstract art in general, and Pape’s art in particular? It is hard to say. Certainly a Constructivist artist like Malevich made work whose associations were political; however, the content of his art remains inherently nonpartisan in the sense that no direct reference to Marxism is made. Pape, whose art would be oppositional to the dictatorship in Brazil in the late 1960s, embraced a style that resonated with progressive precedents, despite the lack of an openly political assertion evidenced in the geometric work.

At the same time, it is wise not to press a political reading too deeply. These works by Pape show that design was strong, as can be seen in the editorial ephemera—books, other printed materials, etc.—that were part of the movement. It is true enough that the group emphasized the connection between art and life, a bias eschewed by many of the formalists working in American and Europe. Yet this emphasis is one of the most engaging particulars of Pape’s career. The artists involved with Neo-Concretism, whose activities were inevitably associated with Rio de Janeiro, eventually separated in 1959 from the Sao Paolo movement, ostensibly for artistic reasons. In general, Neo-Concretist art in Brazil retains a focus on life. In asserting the closeness of art to experience. Even formally they were prescient, as evidenced in Pape’s drawings and the “Teclares” series of prints, which worked with precisely defined forms that still now as if they had been created yesterday. Geometric abstraction continues to be practiced today, but it is a relatively minor activity. For Papes, though, it was a true creative opening. In one work, she even precedes Frank Stella, with a Tecelar from 1956. Although Pape’s work is a woodcut and not a painting like Stella’s, she is prescient in her image of a black background with lines superimposed in rectangular patterns. It becomes clear with the 1950s works that Pape was searching for her own idiom, one that would reflect Neo-Concretism’s predilection for geometric abstraction. Her drawings, as well as the Tecelares, are vigorous and inventive. One might surmise from the sophistication of Pape’s art, despite the fact that Brazil was, at the time, not a participant in an internationalist esthetic, that there are times when creativity rises out of a set of circumstances we would not associate with innovatory art. But Clark, Oiticica, and Pape, the heroes of the time, developed original and often participatory artworks that still look up to date. And it may also be true that they better informed about world art than is assumed.

Divisor (Divider), a 1968 work made use of in a 1990 performance at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio, is a huge piece of cloth with openings for the head. One supposes that the piece, recorded in the show on video, acts to join people together, unified by wearing a garment that brings a large group of people into close proximity. In America, we are used to performance art, but such work usually does not involve the audience. In Brazil, the opposite has occurred: art is made to reach out to viewers and indeed to bring them into the performance itself. At the same time, viewers must remember that the performance, which took place a number of times in Rio in the 1960s, was a not-so-veiled metaphor for the inability of people to set themselves free from a harsh government. But Pape was not always socially motivated. In The Egg, a performance by Pape on a Rio beach, two photographic prints portray, first, a pristine white cube close to the surf, and then, in the second image, a view of the artist breaking through the cube, emerging unscathed from the primal experience. The images are powerful, especially the second of the two prints, and precedes developments outside Brazil in which performance was used to depict life-changing events. In another particularly innovative performance piece, entitled Roda dos Prazeres (Wheel of Pleasures), a group of cups are arranged in a circle on the museum floor. Each porcelain vessel is filled with different colored water treated with food coloring and flavorings. Visitors to the Met Breuer were encouraged to taste the liquids on certain days of the week. Here is another example of interactive art, a genre that Pape developed with considerable imagination.

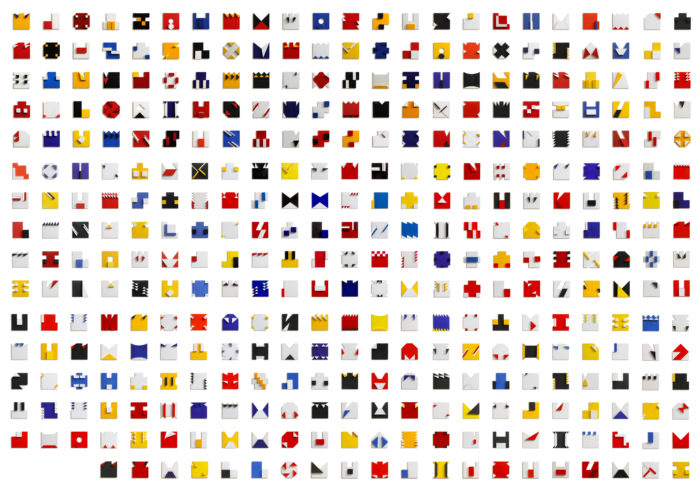

Copies of small interactive sculptures, in both metal and paper, were accessible to the show’s viewers, who could manipulate the pieces of the work in different ways. Again, Pape’s democratic vision maintains itself in work that remains involving as art and, by implication, serves to bring people together. This is a far cry from the protected objects we look at, usually from a distance, in most museum shows! Pape continued to grow as a mature artist; two of her major efforts, Livro de Tiempo (Book of Time) and Ttéia, come later in her career—1961-63 and 1976-2004, respectively. The Book of Time consists of 365 small wooden reliefs, in yellow, blue, and red, that comprises a diary of a single year. The painted squares of wood are sharply different compositionally; they present angular designs that suggest the variations of one day to the next even as they belong to a larger group, which enacts a highly original vision of time. Arranged on one wall in the museum, the group of brightly colored painted blocks developed a visual equivalent of the passage of time—surely something hard to achieve in fine art. Finally, Ttéia, the extensive installation, made extraordinary use of its materials: copper wires arranged in diagonal rows extending from the ceiling to the floor. Looking very much like light descending from the heavens, the groups of wires cross each other as the viewer moves across the floor. It is a work both of sumptuous beauty and ethereal spirituality and is resolutely abstract. No doctrine would explain this investigation on the artist’s part into a realm hardly intimated by her earlier work. But part of Pape’s achievement was her ability to invent new forms to meets the particular needs of the time. Perhaps, too, Ttéia indicates a recognition of religious feeling, as it was a work completed late in her life.

It is important—very important—not to underestimate the extent and depth of Pape’s career. As part of the Grupo Frente, and as someone who had embraced the Concrete Art movement very early in her life, the artist showed a remarkable ability to intuit the most progressive art efforts being made in her culture. When the Neo-Concretists split from their more austere counterparts in Sao Paulo, Pape embraced not only the freedom that the change offered. Not truly a formalist at heart, she showed interest in bringing her creativity into dialogue with people outside the art world. Additionally, she courageously opposed a dictatorship that ruled during decades of her career. In America, we tend to forget just how important it is to make sure that human rights are not eroded by either politics or culture. Although Pape was not an obviously political artist, she actively participated in criticism of the government when this was needed. We cannot push her into the single category of politics, though. It is more accurate to describe Pape as an artistic progressive whose innovations became part of the fabric of her culture. Hers was not a career so much as a calling; her imagination, while not isolated completely (the list of Neo-Concretism practitioners is not short), did assert an independence and a will to change. Both the exploratory forms of the art she was involved in and the presence of political circumstances that desperately needed remediation occupied her extensive creativity. I don’t want to overemphasize the political aspect Pape’s life; she was most truly an artist working out a new idiom for her time. But her social awareness was part of her creativity, surely a sign of her integrity as well as her imagination.

Lygia Pape: A Multitude of Forms was on view at The MET Breuer from March 21–July 23, 2017.

-Jonathan Goodman

Photographs provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art