Hassan Sharif was born in Iran in 1951, and died in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, in 2016. In the 1980s he studied in London, mostly at the Byam Shaw School of Art (now St. Martins), where he came under the influence of Kenneth Martin, a Constructivist artist. In 1971, Martin produced the well-regarded “Chance and Order” series, which consisted of grids on paper, whose points were connected by lines dictated by chance. Influenced by this kind of art, Sharif produced his own ‘Semi-Systems” procedure, in which he both embraced and moved away from abstraction and form produced by accident. The current show at Alexander Gray Associates focuses on Sharif’s interests in the grid, geometry, and repetitive gesture. The artworks have a long span–from 1982 to 2016, the year the artist died. Overall, the exhibition clearly demonstrates Sharif’s remarkable gifts–both in a technical sense and a conceptual one. Fusing a calligraphic hand with a highly developed intellectual method, the artist produced a body of work memorable for its cohesion and creative acuity. This kind of art, as developed by someone whose practice occurred in Western Asia, distant from Western culture, but who was educated in London, is wonderfully nuanced. It demonstrates the ability of contemporary art to extend its insights to a global platform, where its methods can be used, more or less impartially, by artists all over the world.

But whether the internationalization of art will be viewed as a strength or a weakness is something for future historians to decide. My guess is that the loss of cultural specificity will ultimately be seen as problematic; we are trading, worldwide, insights whose conceptual, seemingly culturally neutral origins may allow a wide array of artists to develop but which also seem too rootless to support work that will last. Even so, excellent work occurs now, as this exhibition of Sharif’s art shows. Sharif came from far away to learn about working with grids and coincidence, and he worked with them without bringing his own background into visible play. This looks like it was not a deliberately conscious decision so much as it was an inevitable consequence of time and the resulting decline of art based on a specific legacy. Gifted artists from everywhere now make work whose beginnings are conceptual–because of this, it looks like artistic developments do not have a particular site. But the idea is complex: most in the art world–people in the West–have believed that new art theory has developed in the West, and then taken up by outsider artists from other cultures who had access to contemporary thinking. Yet this view can be challenged: a worldwide conceptualism, beginning in the 1950s, was shown to have taken place in the informative exhibition “Global Conceptualism” at the Queens Museum in 1999, almost twenty years ago.

So Sharif, who was born in the middle of the last century, at a considerable distance from the West, used his education in Britain thirty years later to produce a body of work particular in its expressiveness but not necessarily in its cultural affiliations. His art illustrates our present penchant for shaping practice according to ideas rather than historical legacy. Can it be said that art’s intellectualization has resulted in efforts that are singularly expressive? This would seem to be a contradiction in terms, but in Sharif’s case, it has worked. His drawings feel and look like an abstracted calligraphy; however, they are structured by thought. Because the opposition has both strengths and weaknesses, what really matters is whether the idea underpinning the artwork is effectively realized as art–not thought (no matter how much we think about art, its final form is inevitably understood as visual).

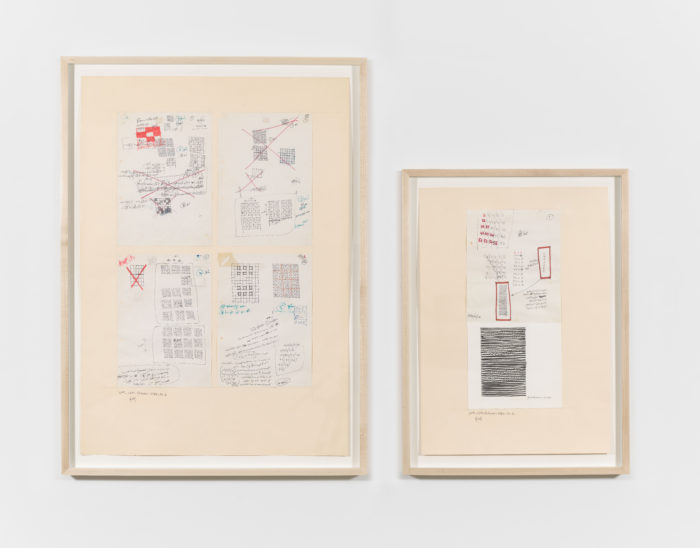

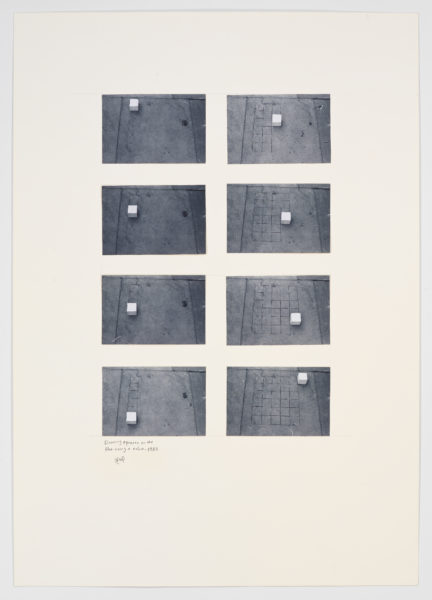

Sharif was excellent in a technical sense, and thus his skill was adumbrated–and, most important, made new–by intellectual insights he internalized thousands of miles away from the United Arab Emirates. One can see this in the early 1982 project, Drawing Squares on the Floor Using a Cube, in which Sharif documents, in eight photographs, his placement of a white cube on the ground. The cube’s footprint was then traced on the ground, forming a grid. The photographs act as a visual device in their own right and also has records of physical activity. So the work is both a visual piece and a document of performance at the same time. The work is extremely smart, and despite the simple repetitions of the image–the only thing that changes is the placement of the white cube–optically compelling. At the same time, though, we can be slightly wary about its intellectual foundations. The piece’s conceptual frame quietly gives it both form and meaning; a work of art cannot come from nowhere. Instead of an artistic precedent, Sharif is using an idea to bring the work about. Doing so frees him from his artistic tradition in the Middle East, but it also pushes the photos into a rarified air of abstraction. This kind of art requires considerable conceptual intelligence to understand.

In America, we have been intent on democratizing culture for some time. A broader audience and greater recognition in art for people from all backgrounds are excellent things–this goes without saying. But contemporary art of the kind made by Sharif inevitably has a limited public; the work is simply too removed, in an intellectual sense, to attract viewers outside the insular (but now international!) coterie following contemporary culture. The result of our attempt to even out and expand art’s audience inevitably becomes something populist, and populism is inherently anti-intellectual. Sharif’s art, which is as good as contemporary art gets, follows a line of increasing distance from a broad audience, something that has developed inexorably from modernism, which pursued abstraction for its own sake. This freed art to examine its own paradigms, but it also means moving more than a bit into abstruseness and losing whatever small contact it might have had with an extended public. Given that many artists remain attracted to the left, the dichotomy between their works’ recondite nature and the wish to build interest among people uninitiated into art’s specialized realm not only seems large but also looks very much like a (deliberate?) betrayal of political principles. Even so, it looks like the gap separating our intentions to cross over to a broadened public will stay. Sharif’s art is so very intelligent, it is clear that it cannot become part of mainstream culture. Maybe this was never possible, but I find that the problem is particularly pressing now when efforts are being made to force art into a more accessible idiom for an unspecialized audience.

But the attempt to democratize culture can only be taken so far. When our backgrounds were not so historically and geographically and culturally complex, it was far easier to reach a greater number of people across class and background. Now, even though the practice of an artist like Sharif indicates that the contemporary thought processes involving art are open to and followed by anyone alive, artists exist in the sad recognition that our audience remains the same–even if it is worldwide, it stays parochial. The kind of intellectual and visual abstraction we find in Sharif’s art requires not only a specialized education, it also needs both analytic and creative intelligence. Because these necessities are rarified, the practice of art has moved to the university–not necessarily desirable, either practically or metaphysically. But this is what has happened. It now feels very true that art schools are providing an art education that teaches students to talk, rather than to develop a high level of skill.

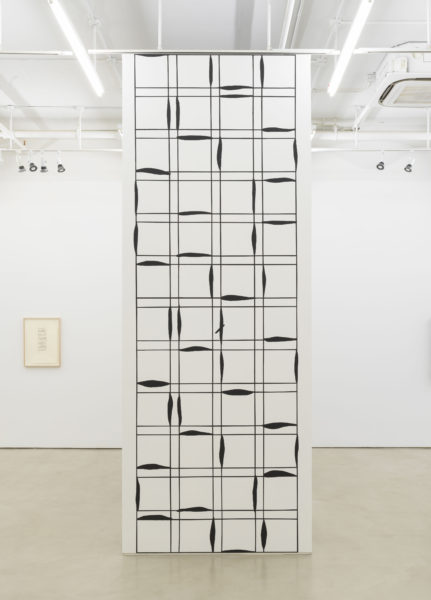

In his own work, Sharif escapes this problem by fusing his conceptual training with remarkable abilities. In his drawings, his hand is wonderfully fluid–you can see his unusual abilities in a couple of drawings in the show: Diagonal Line No. 19 (2008) and One to Thirteen (2008). The first drawing consists of nine rows of small rectangles created by diagonal lines that run upward from the left to the right. These rows construct a vertical rectangle overall. In the second drawing, another vertically aligned rectangle is built by rows of thin horizontal strokes, four to a line. A number of lines are broken up by an apostrophe-like mark, which is substituted for one of the four bands. The whole piece looks rather like a letter rendered abstractly with lines, with inserted apostrophes or commas punctuating the lines. Both drawings evidence skill of a very high order. Given that they feel as ordered as they are as expressive, viewers may regard them as balancing two ways of thinking, rational and emotional. The contradiction strengthens rather than weakens the art.

dimensions variable, courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, © 2018 Estate of Hassan Sharif.

Sharif’s gifts were broader than conceptual projects and calligraphic drawings. He was also a remarkable sculptor. One piece, first thought of and executed by art students–Sharif taught throughout his life–is called Clockwise No. 1 (2008.17); this work was re-created for the current exhibition. In its presentation in the gallery, the image cannot be separated from its support, which is columnar. The piece consists of 12 rows of painted cubes, four to a row. Each cube has a single edge emphasized with a black, slightly bulging line, but the presentation of the lines is random and follow no exact order from row to row. Once again, we have the existence of considerable reason and, at the same time, the visual depiction of chance within that reason. The results, expressed on a 12-foot column in the middle of the second floor gallery, are visually compelling. It is a very beautiful but entirely abstract work of art–here Sharif completely sacrifices his hand, in the sense that the work has been done by others, in favor of an idea-based manufacture. In consequence of this decision, one can assume art can be constructed entirely on the basis of an idea, or from directions given by the artist to his assistants–as happens in the remarkable paintings of Sol LeWitt. Such art is highly exciting in its anonymous determination, but it must be said that the paintings of both Sharif and LeWitt are signed off on the artists themselves–and not the anonymous students and assistants who produced them. It is known that the relations between the artist and his production have become complex and somewhat degraded, in the sense that more than a few well-known artists today have become managers of their creativity, leaving its fabrication to others (Jeff Koons and Zhang Huan come immediately to mind). It is true that workshops have always existed–Renaissance artistic practice was usually based on workshops. Today, in light of current advance, it seems fair to accept such production, no matter whether it is occurring in a small way, as happens in Sharif’s case, or a large. Several of the sculptures in this outstanding show were made in 2016, the year Sharif died. Three sculptures, entirely abstractions, are made of light-colored wooden spars a couple of inches wide. Attached to the wall, the three sculptures offer simple overall configurations–simple to the point of nearly losing their artistic presence. But Sharif wanted here to render commonly employed materials useless as a way of socializing the esthetics of his art. He decided that the wood used for these three works is removed from an everyday context and given a new life as art.

225h x 85w x 18d cm, courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York

© 2018 Estate of Hassan Sharif.

The same thing happens in Copper No. 35 (2016), a work in which eight lengths of coiled copper wire, each of differing measure, hang from the wall. The sculpture is beautiful, but that doesn’t seem to be the point. According to the press release, Sharif understood materials as inherently political. In this piece, he takes a widely available material and turns it into something more than substance alone. As a work of art, it is more or less absurdly simple. But if we see the work as a political contextualization, based on a socialized transformation of the copper wire Sharif has decided to use, it makes sense by means of what it implies. The work thus establishes a precedent for radicalizing materials–this is extremely hard to do! We never associate materials with politics, but Sharif has been able to do so. But the only way we can know this has been accomplished is through our knowledge of the artist’s stand. Like so much art being made today, Sharif’s output demands an understanding of a conceptual and political commitment that he does not directly refer to. Abstract art can only be socialized indirectly; it cannot offer the historical specificity of figuration. Sharif embraced the artistic methods of contemporary art with tenacity and high intelligence, even when these methods pushed him in the direction of an intellectualism that appeals to a very limited audience. The politics originating the very late sculptures are not visually available, but that does not mean they do not exist. As a result, his art is transformed by methodologies and principles that compel us to think and to act with social awareness–qualities we normally do not associate with simple looking. So the work possesses the complexity of a philosophical and ethical command. Finally, though, art is a visual experience above all else. Sharif knew this in his bones, and communicated his knowledge with high expertise.

Hassan Sharif: Semi-Systems at Alexander Grey Associates

January 4 – February 10, 2018

Jonathan Goodman