Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature

The MET

February 8 through May 11, 2025

In nature, the air feels different. While in the absence of man-made life, the sounds of rustling leaves are like a language your soul understands. Born in Greifswald near the Baltic Sea, Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840) was a German Romantic painter considered to be one of the most important artists of his time. Working primarily in landscapes, Friedrich studied in Copenhagen before settling in Dresden. His early works celebrated his deep Lutheran faith, while his later works explored themes of spirituality in nature, the beauty in contemplation, the hopeful promise of a new world order, and, eventually, the end of one’s living existence.

Caspar David Friedrich’s show The Soul of Nature, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 11th, begins its exhibition with early studies that show Friedrich mastering the art of layered compositions. Statue of the Madonna in the Mountains (1804) shows the Madonna and Child rising from an outcropping of rocks while a tiny figure kneels before it, dwarfed by the size of the figures and the tree that stands beside them. It serves as an early example of a landscape that presents its highest peaks in the foreground while the lower landmarks fade into the back; the surrounding sky has barely a hint of air or atmosphere yet dominates half the plane. Eastern Coast of Rügen with Shepherd (1805-6) condenses the landscape even further to the bottom quarter of the sheet, highlighting the closest elements of the composition while allowing the background to fade off, swallowed by the expanse of sky. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem The Shepard’s Lament, which may have inspired the piece, speaks of a longing for the intangible thing just out of reach while a shepherd tends to his flock “full sad the shepherd must be.”

Friedrich found his first success with The Cross in the Mountains (1806), seen in this exhibition as a study in ink and wash. Here we have Christ crucified, a lone figure surrounded by mist and trees. The finished painting was installed as an altarpiece with the gilded and carved frame created by his friend, Gottlob Christian Kühn (1780 – 1828). The painting sets the figure at dusk, with the last rays of the day’s light shining just behind the rocky outcropping that supports the wooden structure, casting a heavenly glow. Some critics decried the use of a landscape as an altarpiece, fearing that the worship of God could be conflated with a worship of nature.

Martin Luther, in his original teachings, spoke of a “Hidden God,” absent when sought, felt but not seen. Friedrich once wrote, “God is everywhere, even in a grain of sand,” reflecting on his reverence for the benevolence of God found in nature. In The Monk by the Sea (1808 – 1810), God’s presence is hinted rather than stated. The land here is a flat, sandy beach, interrupted only by a lone figure whose presence represents one’s devotion to God in lieu of a symbol of Their presence. The sea and the sky converge into a deep blue distance.

Caspar David Friedrich was an artist in Europe during a period of upheaval. The Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) not only brought conflict into his realm but created political change and introduced the concepts of economic mobility and nationalism. Chasseur in the Woods (1813), one of his few portrait-format compositions, shows a small figure in green and gold surrounded by an army of trees, foreboding in their presence, offering no respite or refuge. Behind him, a raven perches on two stumps; both the animal and the trees are symbols of death. Younger trees flank the figure while saplings attempt to fill the emptier spaces, the idea of German liberation as new growth. Completed a month before the Battle of Dresden, the last victory for Napoleon, the artist declined to openly reference the colors of the French army in the soldier’s suit, opting instead to inscribe “Arms yourselves, / people, for the new battle of German Men / Hail your weapons!“[1]

This upheaval inspired Friedrich to explore the ideas of home and its relationship to other places in the world. His once uninhabited seas began hosting ships representing trade and travel. Moonrise Over the Sea (1822) shows a trio watching the arrival of three ships coming into the harbor. Melancholic purples herald the day’s end and amplify the moon, full and rising, shifting from day to night; a metaphor for the transition from life to the other. Meadows Near Greifswald (1820 – 1822) returns the artist to his birthplace where he celebrates the pastoral life featured in the foreground, three horses graze and galavant in the lush greens with the skyline framed in the horizon. Friedrich’s mastery of graduated color is featured prominently in the skies and the meadow that surrounds them.

Woman in Front of the Setting (or Rising) Sun (1818) brings the figure to the foreground. A woman stands with her arms open to receive the light bouncing in the distance. Her back is turned away from the viewer, a Rückenfigur or literally, back figure, a device Friedrich employed often. It serves as an avatar for the viewer as it occupies the space in the painting in our stead. She is both a window to this world and an obstruction from entering. The piece is aglow with warm colors; vibrant hues of yellow and orange create a welcoming sky.

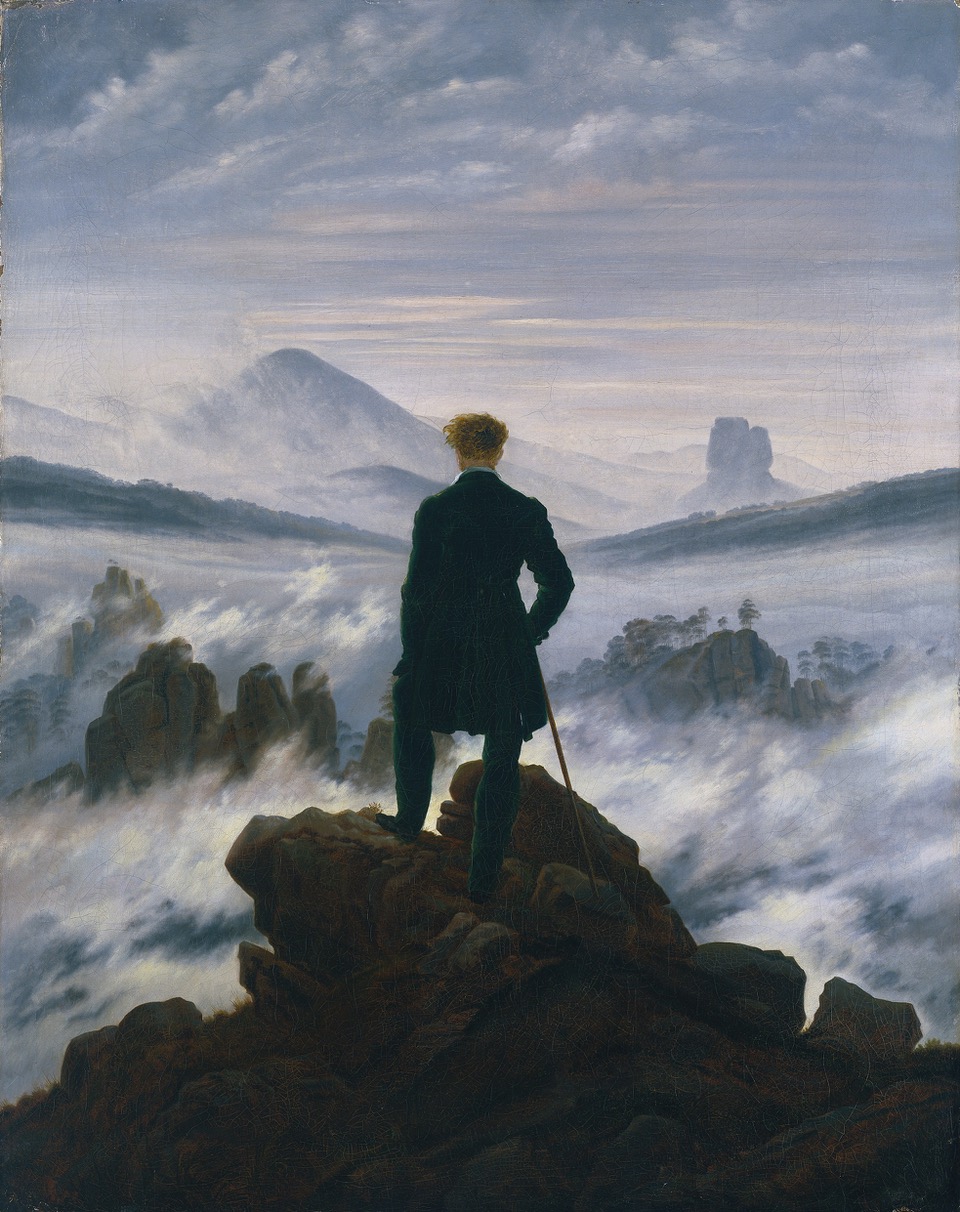

The Wanderer Above a Sea of Mist (1817/1819), Friedrich’s most iconic work, shows a figure rising above rocky peaks and hazy uncertainty, immune from danger in a contemplative perch. The landscape here is an amalgamation of things and different studies pieced together to create a place of feeling, uncertainty, longing, and pensive thought. A pinnacle piece of Romantic art, the mountains in the distance embody the tenets of the movement: power, history, and mystery. The Wanderer stands in command with a leg in a forward pose, active in his engagement with the infinity and uncertainty of the fog that surrounds him. Where Woman in Front of the Setting (or Rising) Sun represents the yin, The Wanderer represents the yang, more active than passive in its approach.

The Wanderer perfectly encapsulates the idea of the Romantic sublime: awestruck by the beauty of nature, confrontational yet fearsome of its unknown depths. While Friedrich explored the ideas of home and away in earlier works, this painting brings both together. We exist in the present, in known surroundings. At home, we are content. In nature, we see the changes as they happen. Day turns to night, and summer turns to winter. The vicissitudes of weather are a metaphor for existence. A fog of uncertainty rolls in, and we are left to decide how to move forward.

Fir Trees in the Snow (1828) and Trees and Bushes in the Snow (1828) are smaller works depicting unremarkable subjects made important by their careful documentation. Friedrich takes care by painting each leaf and branch in detail, and the bushes and trees fill the composition. In these two companion pieces, seen together for the first time in years, he shifts the focus from the hazy sky we’ve begun to associate with Friedrich’s work. Trees are almost abstract, with their dark branches in stark contrast with their surroundings, and the twists and angles of the bush ricochet the viewer’s eye around the painting.

Later works show a masterclass in light and color, a clear confidence in color transition, layering, and line. Friedrich returns to the washes he favored in his early career, but the subject matter is shrouded in themes of winter and death. Graveyard in Moonlight (1834) was created before his stroke in 1835 while his health was deteriorating. Here, we meet an owl perched on a shovel by a freshly dug grave, while three posts are flogged by drapery in the background, the center post revealing a cross. Friedrich had a lifelong obsession with death, creating funerary scenes early in his career. With the grave in the foreground, Friedrich asks his viewer to contemplate the great unknown in his life and theirs.

An early critic noted of his works stated, “No life dwells here but that of air and light,” but the unattended spaces in Friedrich’s works contain multitudes. The artist confronts the Artistolean idea of horror vacui, the fear of nothingness, that “nature abhors an empty space.” By leaving the details of his works in the minds of his viewers to contemplate, imagine, and reflect, we connect with these pieces centuries later as we continue to occupy ourselves with the idea of the unknown.

“When a scene is shrouded in mist, it seems greater, nobler, and heightens the viewers’ imaginative powers, increasing expectation – like a veiled girl. Generally, the eye and the imagination are more readily drawn by nebulous distance than by what is perfectly plain for all to see.”

[1] Grummt 2011, vol. 2, p. 657.