Is there much new that can be said about the great Swiss artist Giacometti? Born in Borgonovo, Switzerland, in 1901 and dying in 1966 in Chur, also in Switzerland, he lived most of his creative life in Paris. The artist contributed in important ways both to surrealism, the Freudian-influenced art and literature movement, and to the existentialist thinking that followed shortly after the Second World War, mostly in response to the writing of French philosophers such as Sartre and Camus. In both cases, Giacometti distinguished himself with a fine sense of artisanal purpose, as well as a remarkable affinity for and sensitivity to the ideas in these modes of thinking. As one of the strongest sculptors of the century, Giacometti made images indelibly stamped in our mind: Woman with Her Throat Cut in 1932 (cast in 1949), The Palace at 4 am in 1932, and The Chariot in 1950. These images manage to speak to the particular difficulties of a century that underwent the vicissitudes of two world wars. In ways that seem meaningfully iconic even now, after the 20th century and well into the beginnings of the 21st. Giacometti made it clear that the war years of extraordinary suffering and the inspired thinking that resulted needed an imagery that could heal the damage of historical events and support accompanying intellectual insights. The truth is that the artist did this extremely well–without submitting his skills to an overtly conceptual outlook.

Thinking of Giacometti, his admirers ask, What is it that has made the artist’s work so powerful, and so representative, a statement? It looks like he achieved his wonderful originality by paring down, reducing the works to their barest statement–indeed, the work made in Switzerland, while the Second World War was occurring, are terribly small. Drawing on a wide variety of cultures, mostly archaic, Giacometti found the visual language for a (Western) world population exhausted by the relentless violence of two global conflicts separated by only two decades. Sometimes the luck of working at the right historical moment(s) follows an artist–this seems to have happened for Giacometti, who managed to remain in the center of things, working with figuration in important ways even though most of his contemporaries were abstract artists. It was not a matter of Giacometti rebelling against the visual gods of the time; rather, working figuratively was a way of being true to himself–we remember that his father was an accomplished, if minor, post-Impressionist who tended to paint scenes of petit-bourgeois life. Giacometti refused to work in this way, but somewhere, deep inside himself, he likely understood that his very human interest in the loneliness of people’s lives would require figuration, rather than abstraction, to be portrayed.

The real issue facing a contemporary audience responding to Giacometti’s art is its relevance, stylistic and thematic, to our lives now. Should his work, as remarkable as it is, be seen as a historical moment at this point in time? Or does it have not only lasting significance in an artistic sense but also as a thematic and philosophical preoccupation? His humanism, tinged with darkness, holds true beyond the years he lived. Indeed, it may be that the darkness itself has made his vision ongoing–other, lesser artists usually do not confront the human condition so broadly. This means that the negative aspects of what Giacometti portrayed–aggressiveness toward women, stated briefly but clearly in a work like Woman with Her Throat Cut, and his unsentimental view of our isolation as individuals–both indicative of the time and, in a larger sense, generally demonstrative of human psychology–continue to pursue us decades after his death.

But thinking so broadly is dangerous: it leads to superficial psychic meanderings and emotionalism. The truth is that the contribution Giacometti made to culture occurred very much in the sphere of feeling, populating as he did the human disposition with a range of emotions that are that much stronger for their objective report. So, in addition to the emotional sphere Giacometti so accurately depicted, we can recognize his ability to show human life with an impartiality that borders on the remarkable in its accuracy. (Maybe much of this impartiality comes from the hidden nature of his psychological immediacies.) Somehow, the artist pulled away from the processes of his inner life in order to explore them as the constructs of everyone’s. Still, it must be remembered that this is hardly sentimental work–one of the greatnesses of the artist is his ability to measure, with unusual precision, the way we damage our idealism with aggression and negatively originating motives.

It should also be recalled that, while it is fair to emphasize Giacometti’s presentation of both feelings and ideas, during his years in Paris, from 1922, when he studied, to 1934, when he ended his involvement with surrealism, he not only referred to inner life as explored by Freud in his art, he also internalized the formal constraints of cubism, resulting in sculptures–heads in particular–that featured the angular planes associated with the movement. The combination of these two qualities led to a body of work that maintained a remarkable formal cohesiveness even as it suggested a world of feeling. While Head of a Woman (Flora Mayo) (1926) doesn’t evince an open cubism, its squarish construction pushes it in the direction of abstract imagery. Painted, with red lips, blue-green eyes, and brown hair, the head had a distinctly flat face–another stylistic arrangement in the direction of nonobjective art.

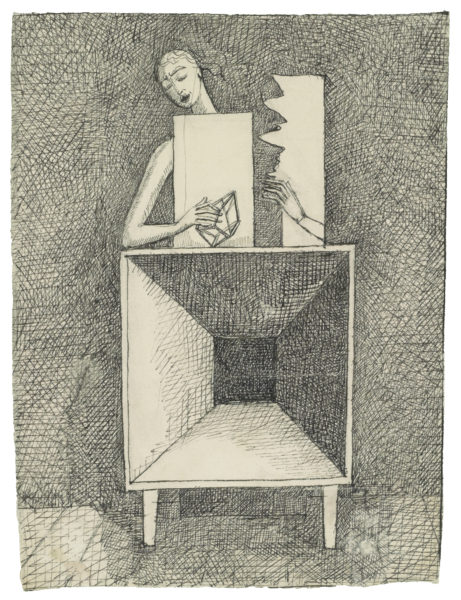

Still, the head is figurative, unlike the remarkable bronze titled Spoon Woman (1927, cast 1954), whose abdomen, deliberately large and concave, looks very much like the hollow of a spoon–but also relates to abstraction. The small head, separated from the belly by a pair of short, rectangular arms, adds to the figurative experience of this work, but it is also true that the overall shape leans in the direction of abstract form. Unlike Giacometti’s later efforts, in which the figure is recognizably realist, and speaks to a universal reading of people, Spoon Woman manages to invoke cubism and the influence of African tribal sculpture at once. Maybe Giacometti’s strength as an artist came from his ability to eclectically assimilate different styles–at least in this period. Surrealist Composition (1933) is an ink-on-paper work in which we see a lipsticked woman whose right arm and hand hold a small cubist sculpture. Her torso is hidden by a flat rectangular white plane, which rests on a table of sorts. A transparent left arm and hand encompasses another plane with a jagged left edge, also resting on the table, which has an open interior leading to empty space. Despite the disparate, unrelated visual references, it is an unusually cohesive image in its entirety.

But none of the compositional imagery of the drawing makes real sense except in the kind of intuition we dwell on in a dream. In Woman with Her Throat Cut, the image moves into the realm of nightmare–the aggression of the image is overwhelming. A work of moderate size, it lies on the surface of its support–the work looks as much like a crustacean from the ocean as it does the skeleton of a woman overwhelmed by violence. Whatever it may resemble exactly, the sculpture is entirely disagreeable in its aura–an ode to negative feeling toward women. We might be tempted to bring in Giacometti’s personal life–his involvements with women–at this point, but it would be a mistake; unless art is openly autobiographical, it is best understood in light of a close reading, one that emphasizes the work and not the artist responsible for it. Highly interesting in a formal sense, it looks very much like a skeletal study–the neck, stripped of flesh, and the ribs are clearly visible. But the components of the composition are clearly separate from each other. One’s overall impression is that of a body in parts. It seems fair to generalize about the piece in a psychological sense; it is a difficult and troubling comment on the antagonism women have experienced for centuries.

Giacometti broke with the surrealists in the mid-1930s; when the Second World War broke out, he was forced to leave Paris and live in a hotel in Switzerland until the conflict ended. His work, now entirely figurative, was also remarkably small–three inches or less–and fit comfortably in a matchbox. Perhaps the diminutive dimensions of the works were a psychic response to the war on his part; it is hard to say. Returning to Paris once the war was over, he responded to its violence with the pieces depicting isolated people–the works he is likely best known for. City Square (1948) is a group of six passersby who are impossibly thin, placed in close proximity but at different angles on a thick pedestal of bronze. The figures are too small to read their faces for emotion, but the overall scene is one of near total disconnectedness. It is a scene of impartially observed alienation–the kind of psychological distancing often seen in the wake of extreme experience, in this case, the hostilities that had overtaken Europe. One cannot speak too highly of this work of art; its dimensions, small to moderate, contain a pathos that is large beyond words.

The Nose (1949, cast in 1964) is a striking work of art that is, like much of Giacometti’s work, unsettling at the same time. It consists of a man with an improbably long, large, pointed nose that extends through the open cube of its frame, put together with very thin columns of steel supported by small, rounded supports. The expression of the male head is agonized, with an open mouth. The pathos of the work is genuine, but it is not so much realistically psychological as it is caricatured. Giacometti was a master of implied psychic trouble, something that comes through very clearly in the sculpture, whose aura and frame suggest displacement, loss, imprisonment. It is a work of major gravitas but moves beyond gravitas into a statement of open pain. The frame centers the head and nose and also cages the bust, which hangs in its difficulties–whatever they may be!–open to the often indifferent gaze of the audience, who inevitably remain distant from the emotional hardship on view. Dog (1951, cast 1957), another abject image, is an absurdly thin sculpture of an animal whose vulnerability remains in our mind. Its head lowered nearly to the ground, its lower body fragmented and raked, the dog represents creature life at its lowest ebb. There is no salvation here–only the persistence of a ragged life.

A final work to be discussed, Standing Nude on a Cubic Base (1953), is done in painted plaster. Moderately sized, it consists of a relatively conventional female figure marked with brown paint. Its arms are impossibly long, and its head terribly thin and small in relation to the whole body. It has the gravity, but not the terror or the anguish, we associate with Giacometti’s work, being a straightforward presentation of a person. Some of this centered sensitivity, available in the sculpture, finds its place in the drawings and paintings of the artist; his portraits of Sartre and Genet remain powerful, moving chronicles of two of France’s best 20th-century writers. His style in these works is agitated, slightly messy, and slightly obscure–in both a stylistic and thematic sense. They offer a way of looking that complements the sculpture; the two-dimensional works feel stylistically tortured, as well as seeming as if their atmosphere was compressed to the point of having actual weight. Giacometti’s world was one of distinct pain, relieved only by the sensuous, if also minimal, style of his art.

To repeat the question that began this essay: How can we push ahead a new reading of the great artist? It seems to me that he is the outstanding poet of desolate loneliness, an alienation not even art can relieve, even as the art shows us so well what such solitude feels like. This places him in a category of universalists, artists who report with high precision on suffering, a quality no one in his audience would be able to evade; perhaps Camus is the corresponding figure in literature. He took a mood, one indicative of the pain following the Second World War, and turned it into something tangible and real. This kind of insight, rendered in a realist approach to people, comes into play very rarely. In the face of the decades intervening between Giacometti and his current viewers, we must see how his art not only relays a position toward public–and private–suffering, it also silently shows us how to face inner struggles by acknowledging their endemic force. This is not so much drama as it is existentially posed. Thus, Giacometti’s vision remains both high and effective, despite its plaintiveness. He must be understood and recognized as both a synthesizer and reporter of great achievement. His subject, our pain, in all its historical and erotic wilfulness, cannot be transformed so much as it must be lived with. Better than almost any other artist in the 20th century, he showed us both our condition and how we must recognize it, given the greatness of his art.

Giacometti at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Jun 8, 2018 – Sep 12, 2018

Jonathan Goodman

Images courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum