As contemporary art sees it, ceramics and glass art here doesn’t quite fit into the general scheme of things—this despite the fact that such major American artists as Dale Chihuly and Josiah McElheny are experiencing great popular and critical express. In particular, the career of Japanese-American Toshiko Takaezu, the American ceramicist, and painter, stands out; she taught at Princeton University for 25 years, and the school awarded her an honorary doctorate. But in cultures other than America’s, ceramic art has never had the problem of existing outside the pale, especially in China, where the genre has reached remarkable heights. Even though ceramics in America exists today on a low profile, and has been relegated to the status of decorative work, if we look closely at historical ceramic art, in America we also have examples of outstanding ceramics. Ceramic work was even made by Tiffany Studios, although it was never fully taken up by the company, which concentrated on glass. Thus, the acceptance of ceramics in the American world of art and design has been ambiguous for some time. But in China ceramic work continues as high art—and is understood as high culture. The noted New York sculptor Ming Fay, originally from Shanghai, created the Garden of Xian in 1998, in which he recreated a Chinese garden with stunning originality in the then-active Philip Morris space across the street from Grand Central. He offered visitors an outstanding re-interpretation of the Chinese decorative tradition.

Unfortunately, Ming Fay’s show did not receive the full attention it deserved; and this neglect points out an ongoing problem in New York art culture: its indifference to the efforts of artists from other cultures. Even though we have more than a few museums devoted to art of particular backgrounds—the Jewish Museum, the Studio Museum, and the Asia Society quickly come to mind—our reception of the art from other geographies and non-majority identities tends to be indifferent. But there is now a tradition in Mainland China that encourages students to study abroad; ceramic sculptor Zheng Dongmei, the subject of this essay, spent a year at West Virginia University in 2006. There, she explains in a written interview: “I learned how to think for myself and keep a critical spirit all the time.” Even if we allow for Zheng’s curiosity in Western culture, she is very much the product of Chinese tradition and education. Born in 1979 in Liaoning, she received both her BFA and her MFA from the Central Art Academy in Beijing. Since 2009, she has been a teacher of sculpture—Zhen is recognized in China as an artist rather than as an artisan—at the Jingdezhen Ceramic University. It is clear that her extensive Chinese education has not prevented her from developing an international outlook. In response to my questions, she gave thoughtful answers, quoting writers as diverse as Pascal, Hegel, Chuang-Tzu, and Blake! So Zhen is remarkably well read, and her intellectual interests elevate her style. She does not find conflict in her job as a professor, asserting that “the current job suits me well because I mainly teach creative courses. In the process of talking with students on creating, I constantly advanced and improved in my thinking…. If one stops thinking and continuously learning, whether as a teacher or a professional artist, one’s position is extremely lamentable.”

When facing the intricate and involved flowers made by Zheng, the real question for the Western art writer or the Western audience turns on our ability to experience the sculptures as possessing a visual integrity beyond that of mere decoration. I don’t think that we are as comfortable with the decorative as the Chinese—hence our tendency to identify it as a minor genre. But the situation is more complicated than that. First, there are times when supposedly minor genres or lesser artists can rise above the limits of the creativity available to the category of art or the person. Second, hierarchies of mediums are increasingly questioned today, in ways that raise the levels of supposedly secondary work. While the assertion that there is no difference in accomplishment or value between greater and lesser genres can be debated, it is clear that ceramics has been taken more seriously here for some time. As for decoration, we merely need to look back at the pattern paintings of the feminist artist Miriam Schapiro, whose work re-evaluated the decorative as a form of originality. Zheng’s art, which is deeply feminine, looks to a way of seeing that is not inherently political. At the same time, she offers no excuses for making work that begins with decoration but moves forward into a world of inspired artifice.

At the same time, the Chinese, whose greatness in painting and poetry has been brought about with a relative minimum of rhetoric, would be able to sympathize with Zheng’s Rococo vision. Her flowers are based on both natural observation and imaginative re-visioning. Asked about her focus on flowers, Zheng describes her background: “Since I was born in a poor family, I had no toys. The happiest activity available to me was going into the lonely countryside, listening to the dialogue between the wind and the trees. I observed the small and fragile wild flowers, and an unspoken happiness took over my soul.” Additionally, the high sense of craft that informs Zheng’s art also originated in childhood, when she encountered the artisanal work done by her mother: “My mother’s embroidery of the curtain on the door, the pillowcase, and the household appliance covers influenced my esthetic and developed my love of ordinary life.” But Zheng is quick to downplay any exaggerated sense of her efforts as belonging to the Chinese legacy of ceramic sculpture, most especially in a historical sense: “In fact, my creative work is not closely related to Chinese traditional ceramics, even though there are many flower themes in traditional ceramic art. The wild flowers and the vegetable flowers I have made remain examples of personal preference.” This would mean that while Zheng cannot help being part of the culture she grew up in, at the same time, she rightly makes her independence clear. In fact, the work does not look traditionally Chinese, but functions rather as an idiosyncratic interpretation of an instinctive understanding of her cultural past. All artists in all cultures both internalize and reject their influences; it is only natural that they do so, given their need to push forward what they already know. Zheng is no different in this case.

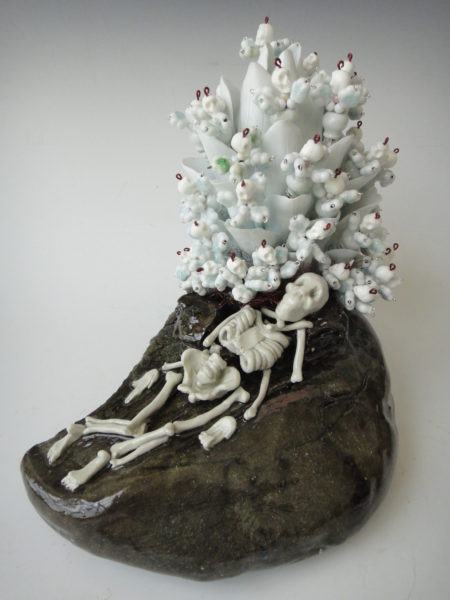

As for the flowers themselves, they embody the exquisite sensitivity that Zheng brings to bear on her art. Again, Zheng’s version of conventional interpretations of her art as decorative is sharply independent. She comments: “Decoration is not the main purpose of my art practice, although many people see this in my works. In fact, I tend more to express my inner feelings about beauty. So my work looks beautiful from the outside. It’s creative motive is clean and simple.” But Zheng also knows the current Chinese art scene, which is, as she describes it, “very contradictory and complex.” The very broad range of art now being made in China—from traditional ink painting to abstract sculpture to conceptual art to performance work—makes Zheng’s art look slightly old-fashioned. But after study of her clay and glass sculptures, the viewer has to rethink Zheng’s motivation and technique. One work done as part of the series One Smile, One World (2013), is 50 centimeters tall and made of ceramic (the flower itself), copper (the stem), and wood (the base). The flower is composed of small white blossoms and green tubes with brown nubs sticking out beneath them. Red berries intermix with the white blossoms. The overall effect is one of exquisite craft and a strict perception of the particulars of nature. It is a work of unusual beauty, although some might claim that the artwork is slightly mannered in its excessive attention to detail.

But that view is actually a mistake. Zheng’s reading of nature is specific, but also romantic, stemming from the early outings in the fields described above. In New York today, where romanticism is hardly embraced as an inspiring outlook, this work would not be easily appreciated. The deliberately beautiful tends to remain within the domain of Asian art, although there are major exceptions (think of noted artist Xu Bing’s grand sculpture of a phoenix created entirely from garbage). But the esthetic of the Chinese, even in art made now, veers in the direction of deliberate beauty. Zheng is a strong artist in the sense that she chooses to move beyond current stereotypes of artistic focus. But she also remains true in some unconscious way to the stylistic attitude of her origins. Yet Zheng takes the risk that her decisions will not receive a full audience, not only in the West but even in China. Mainland Chinese artists in the last two decades have made a habit of being educated in the West; as we know, Zheng herself spent a year in America, during which she actively visited museums and galleries. This might well push them in the direction of a conceptual bias. In China, where the traditional and the contemporary exist alongside each other, both points of view are treated as valid, although the audiences are likely completely different. In regard to the place of ceramics in contemporary Chinese culture, Sheng says the following: “Modern ceramic art has moved from the edge toward a more central position in contemporary art in China, but it is still not part of the mainstream.” This, she says, is true despite the fact that a famous artist like Ai Weiwei has done a highly regarded installation composed of millions of painted ceramic seeds.

As Zheng remarks, there are many official art organizations in China, and local organizations regularly produce ceramics exhibits. But the artist cautions that there is still a long way to go. Another work from the series One Smile One World (2013), made of ceramics, glass, and wood, shows a largish flowering plant that is topped by five transparent glass flowers. The flowers are surrounded by small white bead-like forms, with a heavy naked woman sitting in front of it, on the wooden stand supporting the sculpture. The nude figure has her eyes closed and seems to be dreaming so that the entire composition becomes an exercise in fantasy. Like most of Zhen’s work, this piece approaches caricature in its insistence on the sublime—both of manufacture and theme. This is fine, but is there an audience educated and sensitive enough to appreciate its accomplishment? One worries in general about the art sector’s difficulties surviving a lack of audience; this is true worldwide but especially in America, where very few people outside the art world actively support its activities. In China, though, there is considerable respect for art, even that drawing upon a classical tradition, which is not so easily understood. Even so, the work hardly takes place in a paradise of sympathy. As Zheng explains, “It is well known that China has experienced several cultural catastrophes in its history [including the Cultural Revolution], which has caused local cultural crises, moral crises, and spiritual crises. The generation that grew up in this unstable soil lost its self-confidence. So the cultural and artistic purity of current art needs to be proven.”

One Smile, One World No. 99 (2014) is a very large installation of one hundred ceramic and grass flowers growing out of a sand pile, with a nude woman standing in the middle of the forest of blossoms. It is a work distinguished for its idiosyncrasy and symbolism—as Zheng comments “Carefully look at each flower; they are seemingly countless ceramic frames, echoing the unclothed woman standing in their midst. The work reflects a moment in life.” Obviously, an ambitious work, No. 99 at the same time quietly maintains a disciplined sense of measure that sharply contrasts with much recent Chinese art. Its size is notably large, but the elements making up the installation are small so that the work retains a degree of intimacy despite its grand dimensions. The installation shows us what it means to build a large structure through the repetition of small parts. This has been done elsewhere, but No. 99 remains striking for its maintenance of a tradition that is Chinese—despite Zheng’s insistence on the independence of her imagination (that, though, does not necessarily mean that she is free of outside influence). If it is true that her work is, in fact, independent and personal, it remains accurate to describe this effort as a variation on the great Chinese theme of nature. We can only speculate whether the work relates closely to that theme as the Chinese see it, but the very choice of flowers and natural tableaus such as No. 99 demonstrates the effect of Zheng’s experience in nature as a child, which can be taken as private in kind. As for her art’s public significance, it results from still active ties to nature among contemporary Chinese artists, even though we know the country has severe problems with pollution.

Lotus Tree (2016), a work consisting of two jade-colored ceramic stalks with tightly woven leaves building upward, is purely handmade. Zhen comments that the tree does not exist in real life, but looks instead like a combination of a vegetable and tree. Zheng compares the process of building the circle of leaves to creating a mandala; additionally, we know the lotus has significant religious meaning in Buddhist thought. As the artists say of the two individual components, “There is an inherent healing effect” in both the form and the idea of the two-part sculpture. It may well be fitting to end this essay on works that suggest a religious influence on Zheng’s art. Even though there is no direct reference to spiritual life in her art, its experience intimates a familiarity with nature, a commitment to craft, and a deeply felt intuition for innate beauty in form and materials. While these qualities do not assert piety in any direct fashion, they nonetheless demonstrate a concern for the way the world, and art, is made. This is probably as religious as the Chinese tradition gets. At one point in the interview, Zheng quotes the philosopher Chuang-Tzu: “Heaven and earth proceed in the most admirable way, but they say nothing about them [their processes]; the four seasons observe the clearest laws but they do not discuss them.” This is a sophisticated, Asian version of the Western advice about showing but not telling in art. What Zheng has managed to do is to transform her long acquaintance with Chinese ceramic art, so that her work makes clear a vision of nature and culture that is her own, even if it is not directly communicated. The decorative element in her work contributes to the idea that no matter how intricate the art may be formally, it allows for a view that includes historical awareness, personal originality, and a commitment to nature. This outlook helps Zheng to transcend criticism of her work as “too” beautiful, and brings her efforts truly up to date.

-Jonathan Goodman

Photographs by GUARSH ART.