At the end of Pierre Huyghe’s (2010) film The Host and the Cloud a white rabbit, presumably the avatar for the artist, places a light mask over his face and disappears through a doorway and into the void of darkness. Nearly fifteen years later Huyghe’s current exhibition, “Liminal” in Venice, seems to pick up where that film left off as we enter the dark cavernous space of the Punta della Dogana. Co-curated with Anne Stenne, the artist has transformed the old custom house into a sentient and mysterious world populated with works, old and new.

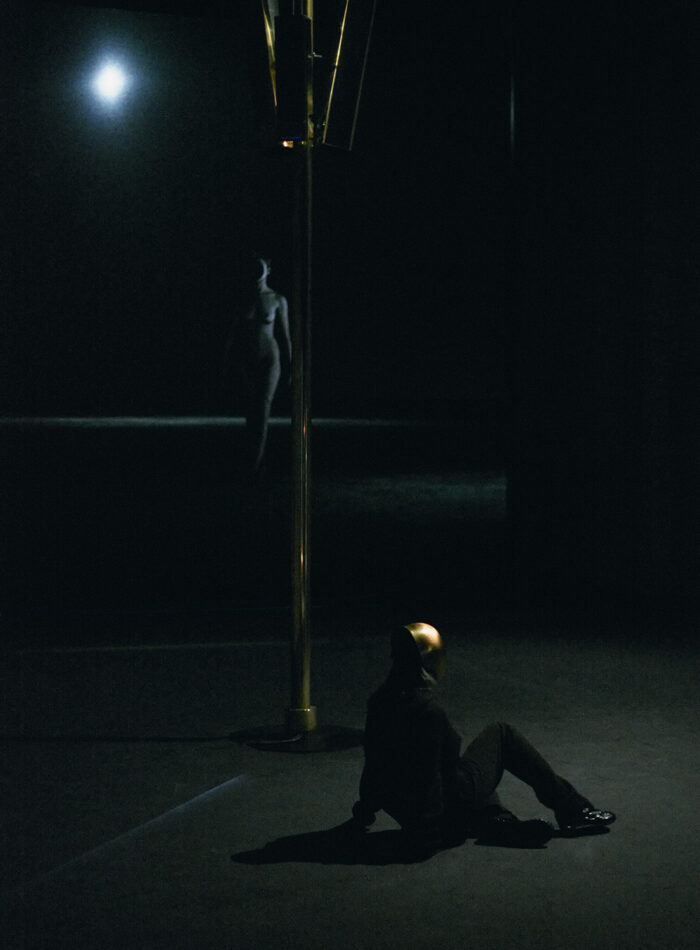

The entrance is dark, so dark that many visitors got out their phones so as not to trip or bump into one another. There one encounters a nude woman, “Liminal”(2024), her face emptied to just a black sphere, gliding sometimes in fits and spurts across an enormous screen, apparently in a transitional state responding to stimuli captured by sensors wired throughout the dimly lit space, which she shares with a tower “Portal” (2024), a brass pole with sensors, as well as “Estalarium”(2024), the imprint of a pregnant belly, cast in basalt. Technology plays such a central role in this exhibition that even the data servers themselves are on display in an upstairs glass enclosure.

When asked about The Host and The Cloud the artist explained that the avatar was reentering the mind, a non-corporeal state – a place of thought and imagination. In that project, filmed over a year in an abandoned ethnographic museum outside Paris, the lines were blurred between fact and fiction – what is scripted and not? who are the performers? and what is left to contingency and chance? In 2010, maybe because he did not yet have AI technology, the artist was still very present, deciding what to film and how to edit. And while there was a grim reaper often lurking in the background, it was still lively with parties, orgies, a fashion show, music, a Michael Jackson impersonator, and a magician. It could be at times sad and melancholic, but also fun, and ironic. Somewhere along the line, all that has all gone and the liminal space we experience now, though still intellectually intense, aesthetically mesmerizing and even poetic is devoid of any frivolity or playfulness, even light.

The notion of liminality indicates an ephemeral space. A term most associated with the British anthropologist Victor Turner, it refers to a transitory state; through seclusion and ritual, an individual emerges into a new self – usually relating to birth, adulthood, marriage and death. In this case the emergence is unknown, even to the artist himself. And that is what he prefers. He does not like to plan the outcome: he sets various elements into motion, which then interact, leak, and bleed into one another. The whole exhibition is arguably about re-birth – what could have been or what still might be.

In fact, one of the most wonderful rebirths might be that of Annlee, the anime character Huyghe purchased in 1999, and famously signed over rights to the image herself, sending the character off in a hail of fireworks, presumably never to be seen again. Yet, in 2012, for his exhibition “Uumwelt” at the Serpentine Gallery, Huyghe showed images to individuals connected to FMRI machines, capturing their thoughts and projecting them directly onto a large screen. In 2021, he found a way to rematerialize the thoughts into sculptures using 3D printers and biotic and abiotic materials. For this exhibition, one of those mental images, is Annlee herself, her distinctive large sad eyes peering from the molded, slug-like embryo on the floor.

There are many familiar works on view, brought together in this new context in which they too are given a new life. The Human Mask (2014), a film eerily set in post-tsunami Fukushima, Japan, depicts a monkey in a wig, white mask and dress. As the rain pours outside, the sad creature continues its domestic kitchen duties as it had done before the disaster, as if caught up in some unalterable time-loop. Aesthetically located between still life and sculpture, Huyghe’s monochrome grey aquariums featuring crabs and urchins, blind fish and rocks and sculpture, and notably a hermit crab in a Brancusi mask shell, alternatively light up and then darken. They are perhaps a reflection of the host city’s Carnival performance as well as its environmental challenges, with its sinking depths and threats to one day become completely submerged. The light boxes of L’Expédition scintillante (2002), with ambient music of Eric Satie, are on view in one of the upstairs rooms where one might find one of several “Idioms” roaming about.

The “Idioms” (2024) are new works. They are real people dressed in black and wearing Bottega Veneta-designed golden bronze masks. A modern take on the LED light masks of The Host and the Cloud, these Idioms are in the process of creating a new language – one not bound by human voice and lexicon but developed over time as the sensors interact with the world, living and nonliving, human and nonhuman alike. The Idioms, are in a way like children who have not been formally trained, or a starling bird or parrot who imitates what they hear; they absorb all sounds and learn by repetition. Masks play a central role in the exhibition – the Idioms, the Human Mask, the fish tank with the hermit crab in a Brancusi head, the woman whose face is emptied. It is a way of acknowledging the multiple selves we inhabit. In different contexts and circumstances, we are strangers sometimes even to ourselves.

The artist originally toyed with the idea of calling the Idioms, “Dorians”, a literary nod to Dorian Grey, the Oscar Wilde story in which an artist paints a portrait, a clone of the original, which absorbing all life’s hardships and the evils of the world, thus initially spares the subject the pain of aging, remaining forever young, at least for a while, until the gruesome confrontation at the end.

Yet time nevertheless marches on, sometimes preserved in archeological artifacts which bear witness to the past, such as in the film De-extinction (2014) in which mating insects are suspended in amber is also on view. Camata (2024), a new film work created for this exhibition, consumes the entire room from floor to ceiling – so large it dwarfs anyone passing by. It shows the real skeletal remains of a migrant who tried to cross the Atacama desert. An area notorious for death, it is one of the driest and darkest places on earth. It is also home to one of the largest space telescopes in the world – the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT), which continuously studies the cosmic radiation echoing from the Big Bang, thus offering insights into the early evolution of the universe. The film, shot over five days, shows the skeleton in its final resting place, now overseen by a camera and robotic arm, carefully picking up and placing objects, including metallic spheres, alongside the body in a constant funeral-like ritual. The footage is shown in a fascinating, never ending, yet always changing loop, edited by AI.

Huyghe’s exhibitions, this one in particular, have become increasingly foreboding and heavy over the past decade. Perhaps this exhibition is just a product of our time. We have lost the ability to communicate with one another – misunderstandings about politics, place and words, and a planet that has reached unsustainable limits; maybe it is time to try again. If we can go back in time, we can better understand and possibly even change the course of history. As Huyghe is always prone to point out, things could have been, and still can be, “otherwise” so in that case, there remains an element of hopefulness.

After enduring the dark narrative of all eight rooms of the exhibition, one exits back out the building the same way one came in. Once outdoors, eyes adjusting to the daylight you can’t help but breathe in, and embrace again the life and smells and flowing expanse of the ancient city of Venice and its glorious Grand Canal.

(Punta della Dogana, Photo by K. Roome)

“Liminal” is on view at the Punta della Dogana, Dorsoduro 2, Venice, March 17, 2024 – November 24, 2024.

Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana are open every day, except on Tuesday, from 10 am to 7 pm. For more information: Information call: +39 041 2401 308

The exhibition has been produced in partnership with the Leeum Museum in Seoul, which will present it in February 2025.

I love this review, which makes sense of an often baffling and complex show. Huyghe’s world is not always a welcoming one and his work can seem impenetrable – wilfully so at times – but Kristine Roome’s thoughtful and beautifully-written piece shows how it can be approached and strands of meaning teased out.

Thanks for the comment.

Thanks.