Namjoo Kim is a mid-career Korean-born painter who studied at the highly regarded Hong-Ik University in Seoul before moving to the Greater New York Area to pursue careers in design and painting. This show presents the artist at her best: her selection of small to moderate-size paintings in translucent inks. Kim’s work offers a fine sense of organic abstraction, made lyrical by the colored inks. Often, the visual language results in spheres and circles that are suggestive of nature. At the same time, we encounter more profound aspects of relatively recent Western abstraction. Her style looks at the New York School but has, at the same time, an ephemeral quality. This suggests an Asian esthetic.

Now, we are living, as artists, in an age of pluralism, which enables people to follow their instincts. Kim’s art reflects the cultural complexity of her current experience, its mix of Korean and American attributes. Additionally, abstraction has been an international idiom since the beginning of the 20th century. It is no longer associated with Western culture alone. Also, the titles of the works point out that classical Western music means a great deal to Kim, who assigns passages of music to listen to while her audience studies individual paintings.

The paintings owe a lot to lyric abstraction. However, Kim’s geographical and cultural affiliations are not easy to read. Kim needs a balance between her experience of two major cultures.

Adagio is a powerful abstract work that is created by several overlays of ink. As noted, Kim has set up classical music excerpts to match individual paintings. Synchronizing the music with the art is rather difficult. There is enough depth in the painting that it doesn’t have to be strengthened by another genre of art.

Adagio offers a blue passage as the first of several layers of ink. Beneath it are green transparent splashes of ink. There is an off-white section at the bottom of the blue area. There is nothing figurative about the painting. Forms suggesting actual things surface, but they are as much imagined as real. But that moment is barely more than that. Kim is working within an abstract language.

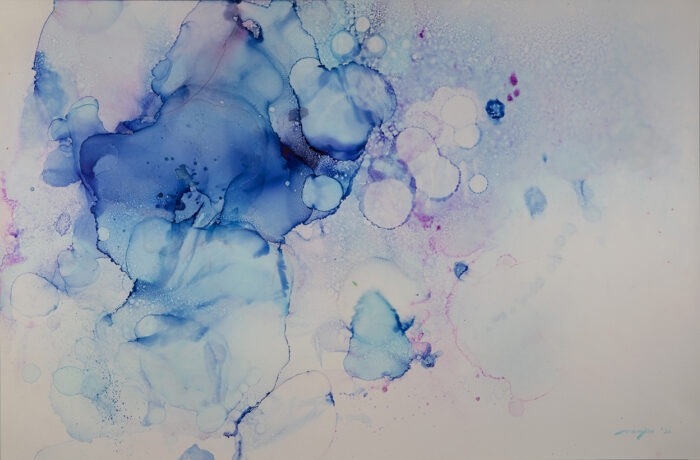

Largo–all the titles are versions of musical terms–is a work dominated by emptiness on the left, and on the right, an area of blue, embellished on several sides by bubbles. The intelligence and structure of the works argue for a self-sustaining vision on Kim’s part.

Kim’s job is to remain as independent as possible. If her social contacts are primarily Korean, the work is not. What counts is the integrity of the art. Kim’s work maintains integrity in the face of two allegiances.

Dante’s Rose is a self-portrait created by mirrors with roses painted on them. The top part, a narrow, oval mirror, corresponds to Kim’s head. A more extensive middle mirror stands in for her torso. The bottom glass, an abstracted version of Kim’s lower body, represents her legs.

The Rose of Dante, meant to represent the mystical aspect of Christ in the poet’s Divine Comedy, is not a Western image alone—Koreans are known for their participation in Christianity. But the roses painted on the mirrors are subtle, difficult to read. They embody the notion of Christ as pure metaphor.

Christ’s symbolic value is equivalent to an imaginative concept, mainly understood in symbolic terms. Yet Kim also described the mirror work as a

self-portrait; regarding her spirituality, she acknowledged she had been active in church but was not presently so.

The roses, painted with subtlety, can be seen as a suggestion: an emblem of Christ that stands between the person and her reflection in the mirror. Perhaps Kim is suggesting that the vanity of the mirrors can be obscured by the presence of the rose, a flower symbolic of spirituality in Western devotional history. Kim’s intimation of self is made literal by the mirrors. What matters is that self-love is transcended.

Camtabile is a triptych of mostly gray, embryonic shapes, with touches of blue, against a three-part, gray paper background. It is a powerfully contemporary work of art. The imagery suggests a heap of stones. This painting suggests nature. Its linear energy, moving over three sheets of paper, can be seen as an abstract narrative.

Maybe this is the best way to think about Kim’s work. We can see it as a still image taken from a story developed by form alone. While the picture does not say anything in the way words do, Kim can still convey depths of feeling. Art depends on feeling. Kim is ethereally inclined, but she works purely in abstraction, a decision doing away with figuration. The tension between art, which is purely of the imagination, and one that mimics recognizable forms keeps Kim’s audience involved; the balance is never entirely in one direction or the other. Kim leans mainly toward abstraction, but her impulse can imitate realism. She excels in fabricating a language that looks to form for its stake. But she knows that such a point of view is a contradiction that is hard to achieve. Kim is primarily interested in emotion, as her titles titles make clear. The connection between specific passages of music and Kim’s visuals also makes that clear.