Joseph Olisaemeka Wilson: Wali’s Farm at Derek Eller Gallery

July 6 – August 25

Images courtesy Derek Eller Gallery

When I saw Joseph Olisaemeka Wilson’s solo exhibition at Derek Eller Gallery for the first time, I was immediately reminded of the Paddington Bear book series. There is something weirdly fascinating about navigating an undisturbed simulacrum through the quotidian narrative of a fictional character—fictional, or at least so I thought.

The tale’s overarching worldview is diagrammatically presented in the show’s title piece, Wali’s Farm (2023): a hen house, Wali’s enchanted well, a central barn with a cat hideout, and crop fields. The farm is tucked away amid an unfamiliar landscape, which, according to the artist’s Instagram bio, is Fennario where he grew up. Recurring motifs such as animal headdresses, farming tools, railway tracks, and derricks communicate a folkloric way of life randomized by succinctly post-industrial grievances.

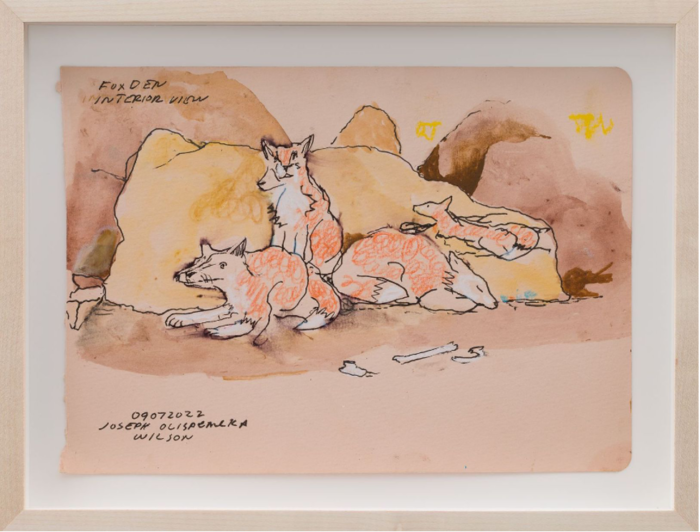

The exhibition consists of oil paintings and mixed media works on paper, all of which zoom in and out of the landscape in quirky ways. Using lighter and more saturated colors, many of the drawings playfully protagonize farm animals such as foxes, pigs, and horses. In the oil paintings, the muddy and earthy palette is punctuated by the bright streaks of colors that highlight the canvases like satellites. Thin washes of warm umber are overlaid with assertive strokes of olive green. Wilson’s technique is impeccable. It resembles a fusion of Basquiat’s motion-filled lines and Soutine’s painterly touch. There is so much to look at, all at once: toy-like mementos, phantom figures, circulation lines, and cryptographic buttons. My eyes fear missing out on information that might contribute to a proper, coherent reading of this narrative.

Therefore, the cardinal question becomes: What is this narrative exactly? The show’s press release includes the artist’s own explanation, Wali’s Prophetic Dream: “Wali sits by the well, whispering to himself a sad song which I don’t remember the title of but I know it is by Rihanna, she’s so convincing in the way she sings her popular songs.” While Wilson refers to Wali using the third-person pronoun “himself,” the artist’s own first-person awareness is almost always phantasmically present. Who is Wali again? At times, Wali seems to be an impersonation of the artist. He could be the man who wears a “W” badge on his chest, laboring on both the farm and the canvas, assuming the role of a creator. He could be a monopolizer of sorts, having the W logo printed on even ham packaging. Wali could also just be an innocent boy caught up in an uncanny dream.

The artist’s writing also complicates the issue of temporality. In addition to the contemporary reference to Rihanna, other historical figures such as Henry David Thoreau and Jean-François Millet enter into this stream of consciousness, pulling Wali’s story into linear historical time. Visually, Wilson also cites art historical precedents such as the Chardinesque rabbit in Butcher at the meat market (2023), or An evening at The Good Love Inn (2023) which hearkens back to van Gogh’s The Drinkers (1890). In these ways, the development of Wali’s story is foregrounded in a kind of realism that alienates the utopian influence of pastoral imagination.

The tale of Wali constructs a post-humanist metaverse, or in this case, picto-verse. Through the “suspension of disbelief,” this immersive world-building urges the viewer to reflect upon identity and subjectivity—can we just pick a character and see this poetic world, foreign and stimulating, through their eyes? Are we to believe that we are Wali, the maker of this dream? Or are we allowed to remain casual spectators and suppress the desire to locate ourselves in the storyline? Emergent, evocative, and enacted, history (historia) plays with the double entendre of chronology and tale. Therefore, Wali’s Farm not only invites contemplation of a visually intricate world but also evokes reflections on the boundaries of reality and imagination. It compels viewers to embrace their roles as observers and participants, as someone else and as themselves.