Joel Shapiro’s excellent art, mostly sculpture, has been with us for a long time. He is a sculptor of very high merit, whose abstractions usually also reference the human figure. The show now up indicates no further advances, but it does maintain the artist’s usual, achieved level of three-dimensional work, as well as ink-on-paper paintings that stay close to the abstract-expressionist tradition. But, despite the worth of the show, it must be said that this sort of abstraction, in both two or three dimensions, is itself a legacy by now–even though it continues to be treated as if it were new. Shapiro, who practices what amounts to historical insight on as achieved a level as is possible, would likely acknowledge that his work takes place within an established continuum of effort. Because of his efforts, or for example the paintings of an artist like Louise Fishman, it seems clear that such styles can still be unusually accomplished on the level of an individual, if also iterative, basis. Yet it is true enough that if art is to go forward, at least now in culture, it is necessary to abandon the past–this has been the mantra ever since Ezra Pound’s injunction “Make it new!” a cultural command he gave in 1935. That is more than a short time ago! Nonetheless, we continue to listen to these words, which may–or may not–still be valid in art.

The problem cannot be solved in a single artist’s work, which cannot but help reflect the atmosphere surrounding him–especially now, when both painting and sculpture feel like they have been overwhelmed by the past. In poetry, to move outside the art world, academic training has resulted in writing that is considerably competent without being inspired. Is the same true of the current visual imagination? It is hard to say; moreover, Shapiro is not in any way academic. But if we understand that Pound’s recommendation is itself a piece of the past, a part of the first third of the last century, it may well be true that his wish has been made invalid by the long trail of what has followed. Even if Shapiro’s show demonstrates more than proficiency in an inherited formal outlook–and it does–our present situation requires a transformed language, which might–or might not–owe its eloquence to previous effort. The large, untitled blue sculpture (2017-18) in the center of the gallery space twists and turns upward with nonchalance, echoing both the artist’s previous efforts and the outstanding history of geometric sculptural abstraction in America, starting with David Smith. The work provides its viewers with the comfort of an already established formalism, but it is also somehow innovative, which is what we terribly need. The sculpture’s height, just over 105 inches, enables Shapiro to elaborate on a theme of wedged planes that rise up and then a bit out over the floor. And the luminous deep blue of its surface, as well as the roughly rectangular, flat faces of its linked components, leads us to believe its orientation is also toward painting.

Photo: Steven Probert.

In the main gallery’s ink-on-painting pieces, Shapiro remains tied to lyric abstraction. These paintings, shown in small groups, repeat a speech whose contours we know well. Even so, it hardly matters, so beautifully handled are the forms. The three untitled works from 2015, done in black, red, yellow, and blue, consist of rounded, irregularly edged blots, which offer emotional, and also formal (and unshaped), eloquence. They declare themselves remarkably well, given their penchant for assertion. Like his audience, Shapiro must understand that this kind of work is somewhat superseded, if we acknowledge our contemporary need for change. At the same time, it is clear that, on seeing even Old Master drawings at the Met, there is a common language recognized not only as acceptable but necessary during a particular time. Younger artists are turning to new technologies to make art, but it is also true that mature artists develop well within criteria we have already seen. Shapiro’s mono-color ink drawings indicate so; they belong to the 2015 series titled “My Dear Friend.” They are as abstract expressionist as can be, which means they are considerably communicative of feeling. Their skill is also high.

© 2018 Joel Shapiro / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Photo: Steven Probert.

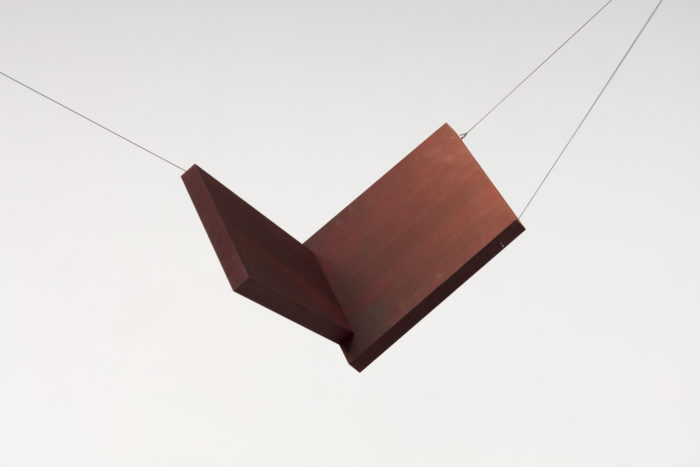

Two small sculptures round out this show: a small piece hung by line from the ceiling and a small wall relief. The first (untitled, 2013-18) is composed of two wooden planes, joined at an angle so that they result in a flying-V form above the viewer. The second (untitled, 2017) is a geometric work, created by four pieces of yellow wood, the bottom three yellow and the top blue. The components are determined by irregularly shaped, flat edges that fit together in a puzzle-like manner. Small in dimension, this work feels like it is a formal problem solved unusually well. In general, Shapiro’s sculptural art looks like a formal abstraction about to make the leap from nonobjective form into something more closely figurative, but this does not happen in the two works described. Here the shapes feel resolutely abstract and stay within abstraction. Now that we are so entirely accustomed to such art, in New York especially, we can read its formal and emotional offerings as if we were meeting an old friend. And so, we are.

Joel Shapiro at Paula Cooper Gallery

MARCH 24 – APRIL 28, 2018

521 W 21ST STREET

Jonathan Goodman

Photo: Steven Probert.

Photo: Steven Probert.