Jacob Lawrence made it his life-long project to document the history, the struggles and the triumphs of human beings — and of the Black Diaspora in particular. Born in Atlantic City, NJ in 1917, Lawrence moved with his family to Harlem in 1930. There he met some of the driving forces behind the political and cultural renaissance that had bloomed there in the 1920s. He studied under artists Charles Henry Alston and Augusta Savage and mingled with the likes of poet Claude McKay. Historian Charles Seifert introduced Lawrence to his personal library of black writers and pointed him onward to the Arthur Schomburg collection at the 135th street branch of the public library — what later became the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

In 1938, a young Lawrence completed “The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture,” a dramatic series of 41 paintings and accompanying text which together provide a vivid biographical account of Haiti’s famed liberator. This narrative series was the first of several that would spotlight personal and collective endeavors toward liberty, justice and a happier way of life: “The Life of Frederick Douglass” (1938-1939); “The Life of Harriet Tubman” (1939-1940); “The Legend of John Brown” (1941); Lawrence’s break-out work, “The Migration of the Negro” (1940-41), now known as “The Migration Series”; and “Struggle … From the History of American People” (1954-1956).

Later in life, Lawrence adapted a number of his early paintings into silk screen prints, including 15 from the original “Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture” series. All 15 of these prints, created between 1986 and 1997, are now on view at DC Moore Gallery in “Jacob Lawrence: The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture.”

In keeping with his larger body of work, these prints exhibit a color palette that is limited, uniform and evocative. Earthy greens, browns and black dominate, yet are interrupted by large blocks of white and splashes of primary red, blue and yellow. A motif of flourishing crop fields can be seen throughout the series. Simplified and angular, Lawrence’s images express both modernity and elements of the ancient African art in which, as Lawrence would later lecture, modern art was rooted.

“The Birth of Toussaint L’Ouverture” (1986) is striking in its intimacy. Just two figures make up the nativity scene of Haiti’s future leader. The rustic, wood-beamed interior in which mother cradles child appears to both shelter and cage. A minimal view outside through a small, square opening is dominated by tall crops.

“The Coachman” (1990) marks Toussaint’s ascension to this post on the plantation where he was enslaved. In the foreground, costumed and perched on his seat, Toussaint steers two horses through the fields. Below in the distance, other slaves cut the crops, their sharp tools depicted prominently. In contrast, “Dondon” (1992), which marks General L’Ouverture’s capture of that city, places L’Ouverture in the fields with his people. Just steps from him, a group of women lift their hands as he solemnly rides by on his white horse.

“General Toussaint L’Ouverture” (1986) is based on a lithograph by Nicolas Maurin that was originally published by F S Delpech in “Iconographie des contemporains depuis 1789 jusqu’à 1829.” Despite L’Ouverture’s son’s assertion that it looked nothing like his father, this portrait was widely circulated and was long the prevailing representation of the Haitian general. “St. Marc” (1994) draws inspiration from another popular image of L’Ouverture seen in an etching by John Kay from 1802. Unlike “General Toussaint L’Ouverture,” which remains fairly true to Maurin’s lithograph, Lawrence conspicuously strays from Kay’s etching with “St. Marc.” He removes the lifted sword from L’Ouverture’s right hand, placing there his horse instead, and replaces rows of soldiers and military tents with a solid block of dark, teal blue.

In “The March” (1995), land and soldiers appear to merge into a beautifully choreographed, revolutionary dance in keeping with L’Ouverture’s use of guerilla tactics. Dense rows of hoisted rifles mirror thriving fields as L’Ouverture’s forces press forward. In contrast, “Flotilla” (1996), which depicts the approach of Napoleon’s forces in a flotilla of ships marked by French flags, recalls both France’s threat and its inherent separation from the Haitian land.

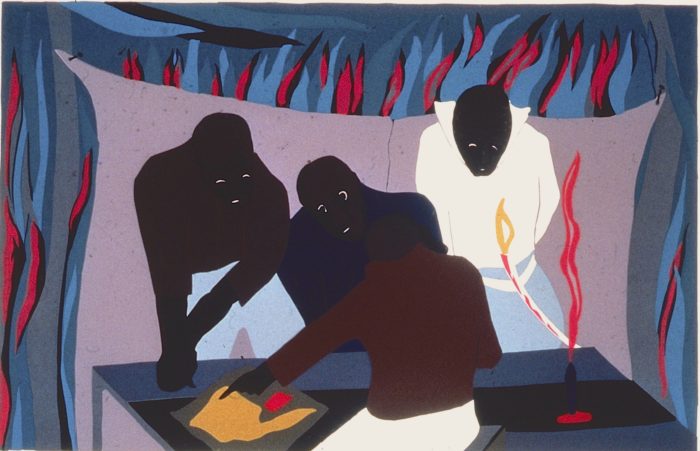

“Strategy” (1994) and “Deception” (1997) bear a similarity in composition as the figures in each are positioned around a single focal point. In “Strategy,” three early chiefs of the Haitian slave rebellion — Jean Francois, Georges Biassou and Jeannot — are joined by Toussaint, at this time aide-de-camp to Biassou, as they huddle around a strategic document. In “Deception,” L’Ouverture has become the focal point. French General Charles Leclerc and his men, armed with swords, surround and capture L’Ouverture before he is taken to the French prison where he dies, leaving the Haitian people to take up arms and victoriously maintain control of their country and their own freedom.

Throughout his career, Lawrence was equally captivated by personal journeys and social movements and sewed them to each other to provide us with a truly global perspective on human society. He looked long and hard at history that textbooks overlooked and diligently and dramatically retold it. He recognized and celebrated struggles for freedom, civil rights and a better way of life. And, as with “The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture,” he imbued black people with honor, strength and pride.

Jacob Lawrence: The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture

January 31 – March 2, 2019

DC Moore Gallery

535 W. 22nd St.

New York, NY 10011

Photographs courtesy of DC Moore Gallery