This means that the pictures we see, usually but not entirely abstract in nature, are linked by a more than human methodology, in which the fine art conveys the magic of an unknown creative tool behind it. As a result “By Any Means” promotes a discussion of the role of random events as evidence of an inquiring contemporary creativity. One can wonder whether such methodologies have become slightly conventional in their own right; the history of such efforts goes back further then one might think, likely beginning with the origins of modernism more than a century ago. Even if that date is a bit extended, it is true that we are, by now, more than familiar with the process of impersonal creation. This show indicates to what extent such creativity has been internalized and put to excellent use by artist who were working and are still working, likely in their prime.

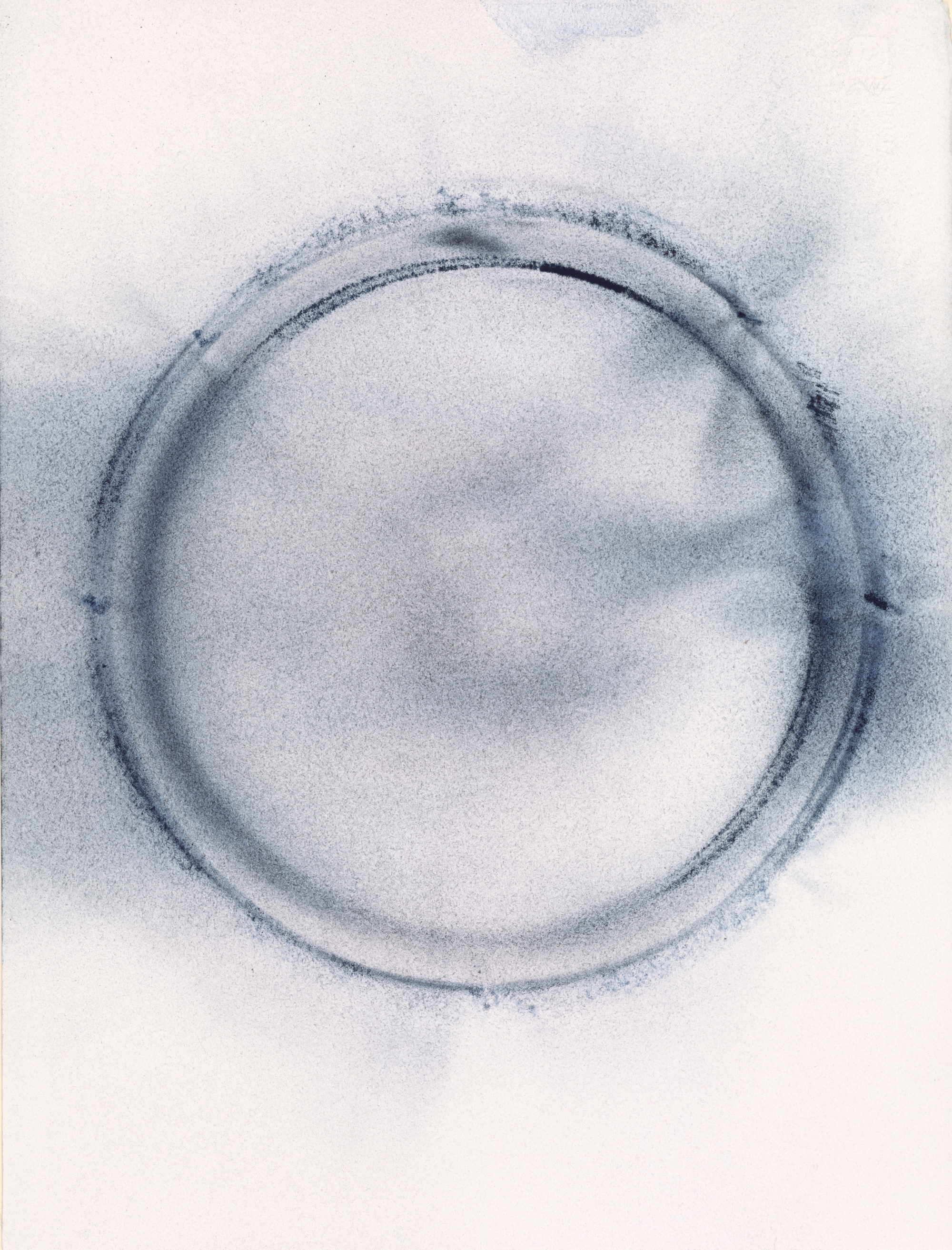

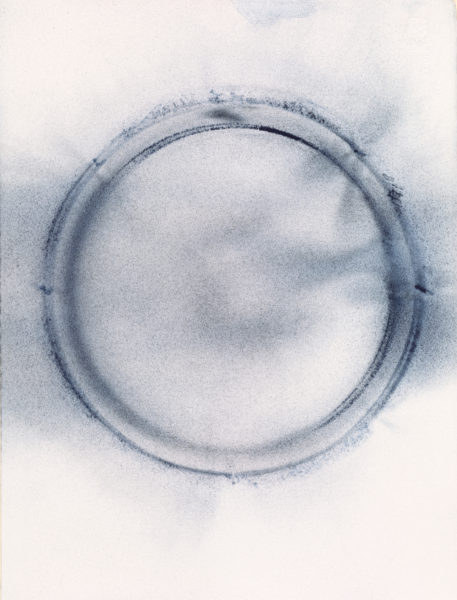

Stephen Vitiello, born in 1964, is responsible for the beautiful Speaker Drawing (22.06), made entirely by the vibrations of a music speaker whose circular rim was coated in slate-blue pigment. The image was transferred onto a sheet of paper by the motion of the speaker as it played music so that the work was produced without any physical intervention on the part of the artist. The round band is darker in some parts than in others, with some color entering into the open middle space and the areas outside the double circle. Amazingly, it looks refined and subtle and even delicate, despite the industrial aspect of its facture. At the same time, the circular image, for millennia a symbol of completeness and perfection, seems to reiterate its emblematic history, although it cannot in any way be viewed as an ancient work of art. Interestingly, Vitiello has constructed a bridge between the clear contemporaneity of his drawing and similar imagery that preceded it. Its simplicity creates something compelling, larger and more complicated than our vision of it–even if our awareness must be informed if we are to fully appreciate what we see.

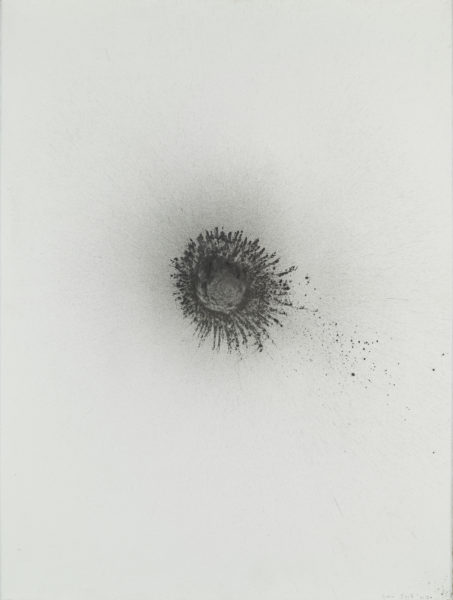

Rosette (2013), by Gavin Turk, was created by exhaust emission onto paper mounted on linen. The dark-gray image is small, centered in the field of composition. It looks like a photo of what happens when a drop of milk hits a level liquid surface: the circular center is slightly depressed, with a coronet of thin, narrow beads surrounding–the consequences of the overflow of the exhaust. A rosette is understood to be a rose-shaped decoration, sometimes uses as a badge of merit, a recognition for winning a competition. Turk, now in his early fifties, is a Young British Artist who is no longer young. But Rosette is youthful in its form, spirit, and methodology. Like Vitiello, he wants the work of creation to be achieved by forces other than his own. This is a complicated process; it emphasizes the endless possibilities of a creative industry beyond human touch, which may–or may not!–be a good thing. But in the case of both images, the visual experience seems at least as human as it is mechanical; we can only speculate, if we do not know the origins of their making, the extent to which the works reflect Vitiello and Turk’s hand.

The emphasis on abstraction in art in the second half of the 20th century and through the present moment may well have pushed image-making into the direction of greater and great impersonality. Doing so shifts the discussion from a personal reading of the artist’s sensibility to an awareness that art can be treated in a way that minimizes human presence, even as it develops a visual cohesiveness that is highly attractive generally to people. Abstraction has always existed in art, but it is only in the last hundred years that it has been isolated and treated as an imaginatively compelling style in its own right. Not all of the work in “By Any Means” is abstract, but a lot of it is, signaling to its audience the preference of many artists for work that refers to form alone, beyond and outside the human body. Paul Jenkins, the American abstract expressionist painter living in the twentieth century and working both in Paris and New York, contributes a smallish, untitled ink-on-paper work from 1954. It is a model example of the kinds of effects we expect from an artist working in this style: tonal modalities ranging from gray to black, forms that defy a linear outline, no obvious connection to anything recognizable.

Jenkins’ piece epitomizes the free-form, emotionally direct quality so popular in the last century and still today. The drawing is highly dramatic, with a series of vertical pole-like forms, most with rough edging, jutting upward while being surrounded by amorphous washes that are darker toward the bottom than they are on the sides. There is no figuration being suggested in the composition, which is really about the visual effect of form alone, outside known reference, as well as the tonal complexities achievable with ink by itself. Jenkins may not be as well known as his other New York School colleagues, but an image such as this argues for a permanent place among them. Another deliberately informal, deliberately messy image, Untitled (mm16.31) (2016) by the Swiss-born, Brooklyn-based artist Christine Hiebert, is constructed from blue tape, ochre, and graphite on watercolor paper. The imagery is various: on the lower left, there are two thin, vertical ribbons of blue tape; in the middle, on the right, are horizontal forms ochre in hue; and in the upper right, we see ascending smudges of graphite. The image is random, messy to the point of caricature, but its original forms, colors, and materials make it strikingly interesting. Hiebert shows that the New York School is alive and well, if perhaps a bit idiosyncratic due to its long existence.

The late Jannis Kounellis, the founder of Arte Povera, a movement resisting Italy’s post-war rise to affluence, is represented with an unusual untitled drawing from 1979, which presents scratches on a ground of crushed charcoal. It examples the show’s interest in unusual materials construction as well as objective manufacture. The white scratches, ranging from small blotches to thin lines oriented in all directions, can be likened, as the artist commented, to drawing on water. There is a surreal, earth- (or, rather, carbon-) based orientation in this and most of Kounellis’s art, which attempted to salvage the place of gravitas in a world society increasingly commanded by heavy industry and capital. This work, while not overtly political, indicates an intuitive understanding of the process that is akin to the way we can say nature operates. The random marks amount to a re-ordering of–even a rebellion against–hierarchical ordering: another way of circumnavigating the problem of excessively linear thinking. White lines on a black background reverse the expectation of black on white, and in working like this, Kounellis once again voices an opposition to convention. Even if the drawing is not a major work of art, it is an exceedingly fine example of a great artist’s esthetic.

It might be of interest to consider, for a moment, the vitality of this work in comparison to art made before the outbreak of modernism. Much of the work in this show examples methodologies and materials not available earlier, as well as a preoccupation with a chance esthetic that is only a couple of generations old. We think of Rauschenberg’s long-established work with random events in his work, or John Cage’s use of the I Ching to influence, order, or even entirely determine the forms of his art. Now that we are free of representation as a dominant mode of artistic expression, we have become free in our approach to creative methods. But it is also true that this procedural freedom now possesses a history beyond several generations–a longevity that inevitably results in its own constraints and rulings. Is it possible that the chance-driven works we see here will take on an aura of anachronism in the future–or can we assume that procedural innovations established a long time ago can remain as fresh and new as they were when they were originated? It is a difficult question to answer, although, to some, the results of process-oriented art that is heavily influenced by the haphazard incident may be, at this point in time, technically redundant. “By Any Means” brings this question to the fore.

Robert Rauschenberg, a leading exponent of chance in art, is evident with his untitled drawing from 1973. Done with opaque paint, watercolor, and graphite on brown paper, the image consists of two shapes on the left and three on the right, all five of them painted with white paint, through which the brown paper shows. On the upper left, we see a horizontally aligned rectangle, beneath which is a small group of white smudges. On the right, the three images include, at the top, a vertically placed rectangle; in the middle, another rectangle with an appendix that looks like a peninsula on its bottom right; and beneath the middle image, a rectangular parallelogram. The outer edges and the middle of the paper are unadorned. This work, like many in the show, is highly improvisatory and informal; it denies any hope of organization. But that does not mean it is not accomplished. Rauschenberg was a master of the extemporary, which means that he knew how to make images in the same way the great musicians of the 1950s made jazz. We don’t know now where this automatic creativity will proceed, and we remember that more than a few images in this show are by artists no longer alive. Still, that hardly means that art made by accident is moribund. “By Any Means” shows us that imagery determined by incident is more than historical; it is alive and well in the works we see brought about by late and living artists. We can only hope that the process will not exhaust itself, given that the art in the show is not only memorable but also salient to the way we live now.

Jonathan Goodman