The exhibition “74 million million million tons,” brought as its name suggests much weight and meaning. But like a lot of Conceptual work, what I saw was not always what it appeared to be. A jumble of cell phones and wires spread on a low platform on the floor, and a vending machine filled with strange looking grey bars were just some of the installations I encountered on entering the front gallery of SculptureCenter where the show is on view.

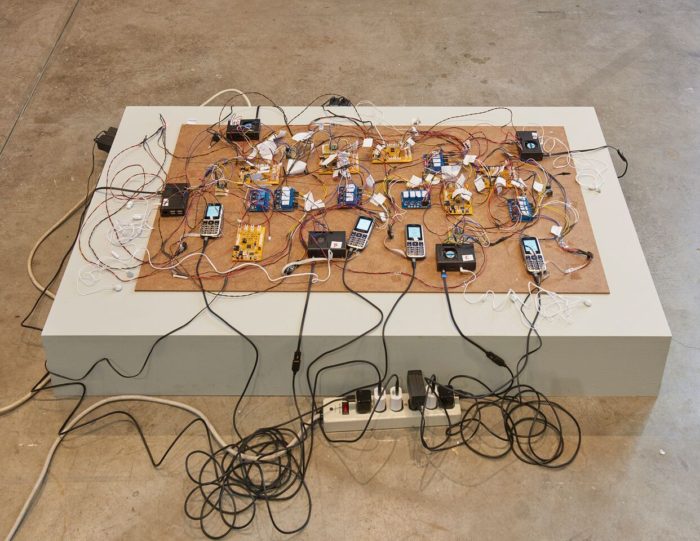

Curated by Ruba Katrib and Lawrence Abu Hamdan, ten international artists parsed a variety of subject matters to investigate liminal states of visibility. By this, as was stated in the press release, the occurrence of certain events or shifts in socio-political and technological realities, whose consequences are outside our immediate “perception and detectability,” become crucial to the artists’ investigative process and aesthetic lexicon. Hence Shadi Habib Allah’s accumulation of cell phones in “Did you see me this time, with your own eyes?,” 2018, represented how Bedouin smugglers use 2G cellular networks to communicate surreptitiously. For these long-oppressed nomadic tribesmen from the North Sinai Peninsula in Egypt known to smuggle goods from Egypt into neighboring Palestine and Israel, coded signaling is key to avoid any confrontation with the authorities. The tangled cell phones and cryptic recordings, which the artist obtained, became symbolic of a space and world situated on the periphery of legality and one that is hard to access or penetrate.

But just as I felt that Allah’s explanation of his attempts to decode the recordings during the press conference was far more intriguing than his somewhat prosaic display, Susan Schuppli’s video series “Nature Represents Itself,” 2018, about British Petroleum’s (BP) Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico suffered no such schism. While the actual explosion of the drilling rig was shown on a small non-descript monitor in the main gallery, a larger screen in a back room captured the mesmerizing movements of the waves filled with iridescent colors that reflected off the oil floating on the water. As the shifting rainbow palette in the ocean captivated me, Schuppli’s extensively researched and informative voiceover explained the repercussions of the massive damage to coral reefs, water patterns, birds, and sea life that had conveniently been obfuscated by BP. In this way, Schuppli’s images of the oil spill created a marvelous double-edged aesthetic vocabulary. Questions about human culpability and the unforeseen long-term effect of such catastrophes were deeply embedded in the alluring map of colors on the screen.

A similar kind of probing about the precariousness of truth could be seen in Hiwa K’s video “A View from Above,” 2017. Detailed computer generated street maps of a bombed city derived from real life statements are memorized by M, a Kurdish refugee in the video. M like other refugees from northern Iraq (Kurdistan) deemed to be a “safe zone” by the UN must claim to belong to the reconstructed “unsafe” war zone in the video in order to gain asylum to the Schengen countries. Here Hiwa K does not depict reality as much as he insinuates the violent effects of war, trauma of refugees, and the inhumanity of government officials. Like most memorable hybrid works that combine fact and fiction, the video’s impact laid in the way it opened up a larger reality comprising of tragedy and farce.

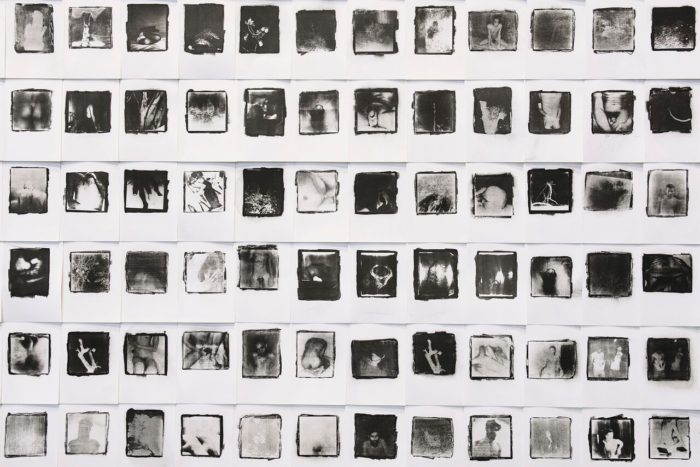

If good conceptual art might be defined by the way it suggests its central idea to the viewer, George Awde’s 2016 untitled series of photographs taken in Lebanon raised complex issues regarding the male body, identity, and voyeurism. In this installation, seemingly abstract images obscured with gum arabic and graphite revealed forbidden clandestine male relationships on closer inspection and hinted at the ongoing tension between artifice and reality in the works and in the Middle East.

In this way, the best works in the exhibition explored spaces and opened worlds that one doesn’t normally encounter. Whether it was Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s brilliant animated farcical video “EVA v3.0: No right way 2 cum,” 2015, made in response to a recent ban on female ejaculation in UK produced pornography, the artists deftly invented new lexicons of ideas and aesthetics. Even if some works like Sean Raspet’s environmentally conscious Nonfood algae-based line available in the vending machines didn’t seem particularly enticing, I was spurred to keep searching for answers to the questions planted in my mind.

Participating Artists: Shadi Habib Allah, George Awde, Carolina Fusilier, Sidsel Meineche Hansen, Hiwa K, Nicholas Mangan, Sean Raspet and Nonfood, Susan Schuppli, Daniel R. Small, Hong-Kai Wang.

74 million million million tons at SculptureCenter

April 30th – July 30th, 2018

Writing by Bansie Vasvani

Photographs courtesy of SculptureCenter