Born in 1980, Wu Jian’an has been an associate professor of experimental art

at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. While in graduate school

there, Wu studied paper-cutting techniques, eventually devising an

innovatory process, in which the complicated cut pieces of paper would be

placed on a single monochromatic sheet. These sheets would be layered

on top of one another until the work attained the form of low relief. The

themes of such work involved Chinese mythology. But 500 Strokes, the

show’s title, offers a different kind of art. For this body of work, Wu invited

participants to choose a particular kind of brush from his collection, as well

as the density and color of the ink used; the person would then create a

single brushstroke, without referencing either a recognizable image or

calligraphic stroke. Strokes by many participants in Wu’s studio game are

then collaged onto a larger piece of paper, in a way that is so subtle as to

appear seamless, without layering.

The works themselves reference modernist and contemporary painters

from the West, including such artists as Mark Tobey and Brice Marden. As

for the strokes themselves, they may be either “good” or “bad” according to

the Chinese view, but their placement in a single composition allows Wu to

work with a range of effects, which to someone living in New York City,

looks very much like a new version of abstract expressionism. 500

Brushstrokes #73 (all the works in the show are dated from 2021) consist

of broad, black curving brushstrokes on the topmost layer, underneath

which we see a large, bulbous black form. Underneath this rounded shape

is a green band following the black form closely. On the right, there are

three masses of black, two of them made of thin, individual strokes allowing

the lightness of the paper to show through, and the other, purely black.

Beneath the last mass is a group of light pastel colors: pale peach, light

green, and a bit of pink. The piece exists at a good distance from traditional

Chinese painting, although its facture, in particular the attachment of the

brushstrokes in such a way that they feel like seamless passages of color

rather than collages, is deeply Chinese. Still, the painting strikes the viewer

as more Western than Asian.

Brushstrokes #78 is nearly a caricature of abstract expressionist form. With

a major, black curling stroke on the left, and an equally sinuous, curving

yellow-green stroke on the right, the composition announces its allegiance

to contemporary abstract art, created by more than a small number of

people. On the bottom left quadrant is a series of jade green/gray vertical

strokes, while on the bottom right, there is a series of thick strokes

gray/black in color. At the top, across the width of the composition, is a

complex array of mostly black, highly abstract effects, including an organic

mass of curvilinear black lines. The piece examples no evidence of

Chinese manufacture. It seems to tie in much more closely with Western

painting of the last fifty years.

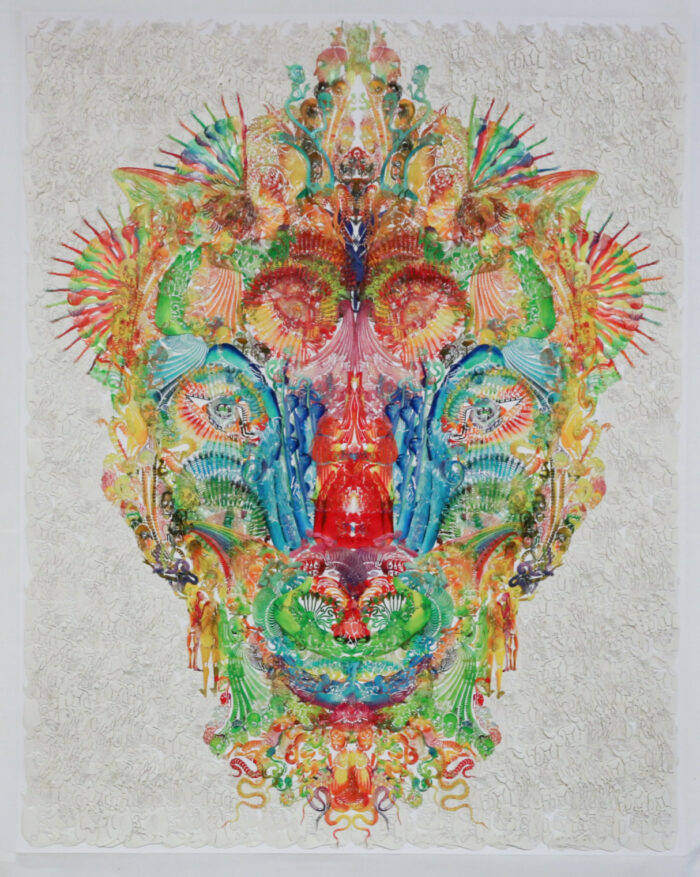

The final piece, Shapeshifting Deity, is a Hand dyed and waxed paper-cut of astonishing

complexity. The head looks very much like that of a tiger’s, and the colors,

too numerous to mention, express themselves in a detailed fashion, filling

narrow shapes and forms. Hand-dyed papercuts detail a bright red nose,

eyes of animal-like intensity, and a series of bulbous, multi-colored masses

on the head, from which protrude thin spikes. Clearly representational,

despite they myriad small forms it consists of, the deity comes across as a

vehicle of ferocity, capable of changing form from one moment to the next.

As a paper cut, this piece dates back to earlier efforts by Jian’an. The show

throughout demonstrates remarkable skill and also an awareness not only

of earlier traditions but also of much newer art. Wu has produced a

compelling body of work, incorporating not only technical skills but also

conceptual advances, which make him a notable artist.