Video walk-through of Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945 at the Whitney Museum of American Art

Feb 17, 2020 – Jan 31, 2021

All images courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art

This remarkable show of 200 works establishes a scholarly precedent for a great moment in the history of Mexican art, when, following the revolution (lasting from 1910 – 1920), the great triumvirate of Mexican artists–José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros–created a broad, often mural-based imagery that celebrated the working man after the country’s revolution in 1920. These major figurative painters not only benefited from the sweeping change that was occurring in Mexico; they also spent considerable time in the United States, benefitting from its progressive modernism in art, as well as its near apotheosis of the worker, often portrayed in the setting of industry. Barbara Haskell, the exhibition’s chief curator, has done an excellent job of portraying not only the great achievement of the major players but also the effects of the movement on artists from the United States, including Jackson Pollock whose seismic early figurative style, not yet developed into the expressive abstraction he would become famous for, owed much of its force to his experience with Siqueiros’s workshop in 1936 in New York. As the title of the show indicates, the three major Mexican artists exercised considerable influence on the American figurative painters of the time.

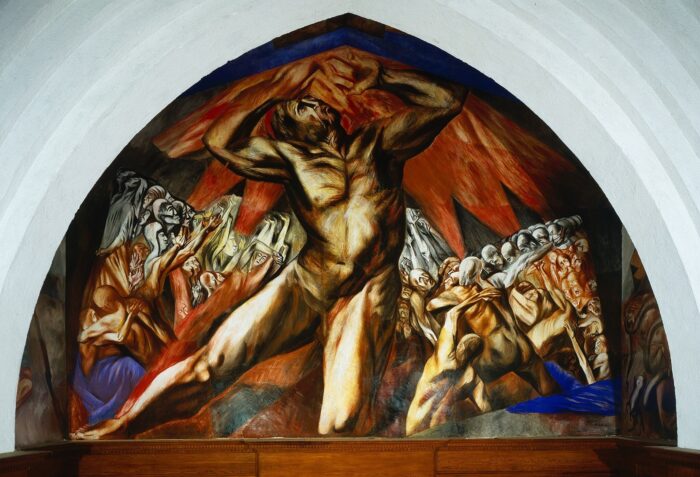

One of the chief pleasures of the show is seeing major works by each of the three most recognized Mexican painters. Orozco is particularly well represented; his turbulent, muscular style sets the stage for a visual rhetoric that must have seemed overwhelming at the time, even if today the expressiveness can seem slightly melodramatic. In his powerful painting Reproduction of Prometheus (1930), shows the naked mythic figure twisting his body in front of us. Behind him is an array of women with their heads covered by scarves. Prometheus is known as the mythic figure who brought fire to the world, and who was punished by Zeus for doing so. But what better metaphorical narrative could there be for an ongoing revolutionary stance? The fresco painting forcefully illustrates the torment of someone bringing a dangerous gift to human beings. Jackson Pollock’s extraordinarily expressive painting Untitled (Naked Man with Knife) (c. 1938-40) is filled with nearly blood-red naked bodies. One of the figures holds a sharp dagger angled downward in the top left of the painting. Like Orozco’s work, Naked Man with Knife is about representing transgressions whose consequences are large and disturbing.

The stated aim of the exhibition is the documentation of the muralists’ influence on American artists. The show makes this point extremely, successfully, including the works of artists as disparate at Thomas Hart Benton, Jacob Lawrence, and Philip Guston. “Vida American” also successfully presents the Mexican customs and homelife–a studied contrast in regard to the usual pursuit of European culture. One can see this in the painting Flower Festival: Feast of Santa Anita (1931) in which three younger girls, dressed in white and wearing colored headbands, kneel before a man hunched over by the green plants he shoulders before them. There is also the compelling, humorous self-portrait of Frida Kahlo, entitled Me and My Parrots (1941), in which the painter, with her trademark heavy eyebrows, faint mustache, and hair swept up in a bun, wears a peasant blouse. Two parrots rest on her shoulders, while two are in her arms, which rest on her lap. Part of the revolution’s cultural consequences was a shift from European to indigenous influences, as shown by Rivera and Kahlo. What has not been known so well, and what this very strong exhibition does most excellently, is to show how the Mexican work of the time heavily influenced many important American artists.