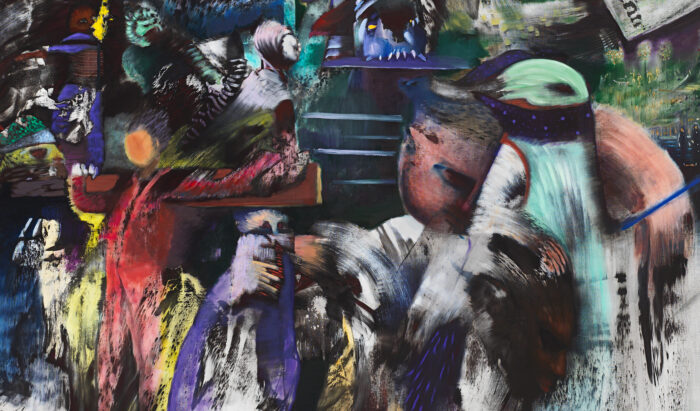

Ali Banisadr’s first solo exhibition with Perrotin, titled Fortune Teller, is a series of visions about human civilization brought forth from his Brooklyn studio to the gallery’s Shanghai location. The eleven paintings operate in a language directly between Baroque narrative and allover Abstract Expressionism. Each work gyrates with an ancient motion that, if audible, might sound like the deep chords of a haunted church organ—an instrument resonating so long that it has shed the weight of insignificant details. Luscious tonal gestures sweep evenly across each visual field, like a De Kooning or Pollock; but granted the attention they deserve, the storm clouds of bold painterly marks reveal an interior geometric structure, informed by historical compositional methods and architectural forms. For the patient viewer, Banisadr’s classical education is on full display.

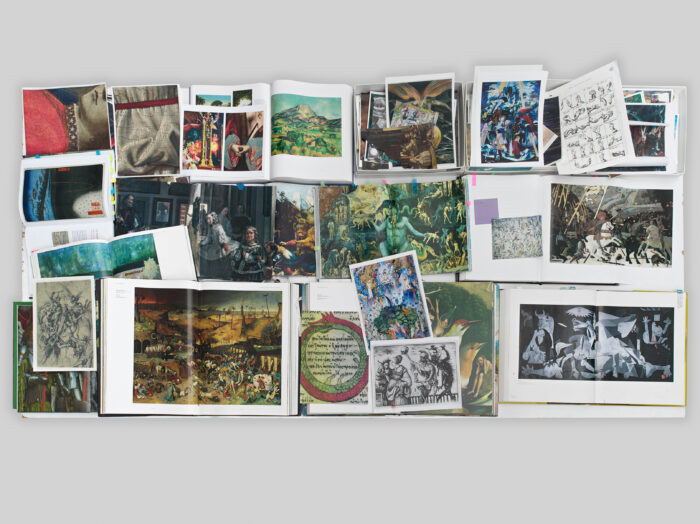

The artist creates his paintings one at a time, laying out art book pages on a large reference table—a palette of ideas. On this table, Picasso sits beside Velázquez and Cézanne beside Bosch. He begins his work by mixing and tubing paint to establish a tonal range of bluish-blacks and five distinct whites. After contemplating the canvas and its compositional energy, Banisadr applies these premixed tubes to create Rorschach-like stains of shadow and light, forming a vital groundwork capable of evoking ideas in the artwork. Slowly, apparitions of dreamy Chagall-like color, expressive figuration, and ambiguous narratives emerge.

The geometric anatomy of these paintings allows the picture plane to function like a stage set. Viewers can explore smaller, self-contained scenes within the larger production or step up to the nosebleeds for a wider perspective. The Mirror World is an example, filled with motifs and strange characters holding or peering into mirrors. These figures’ faces are often turned away, leaving their reflections as the only clue to their identities. The mirrors suggest allegories for the technological looking glasses of our era—devices in our pockets or shoulder bags—but Banisadr’s choice of timeless mirrors over contemporary screens is indicative of his visual language’s universal core.

In The Land of Miracles, rectilinear frames within the more extensive composition recall Jan van Eyck’s principle that a painting should comprise smaller paintings. Banisadr has embraced this way of thinking throughout his new body of work to enhance the simultaneity and indeterminacy we experience when interacting with the images’ narratives. With a title like Time Collapse, the artist is clearly invested in intensifying the temporal dissolution fundamental to two-dimensional art.

Banisadr has carefully worked toward the collapse of time by designing interaction zones within the larger compositions. These zones act as portals wherein figures and their narrative relationships emerge in small touches of paint from the sweeping gestural groundwork but also fragment into other possible figures and interactions. Those fragmentations open us to new narrative pathways and move us toward a sense of the human experience unencumbered by time. Ambiguity creates multivalent possibilities and multidirectional movement. We become travelers within his compositional framework of time, space, and anatomy, untethered from the certainty of clearly defined facial structures, narrative plotlines, or specific social contexts of human history.

What is special about Banisadr is that, unlike many contemporary painters working in the figurative tradition, he decidedly stops short of delivering us subject matter. His dense, complex, and fragmented narrative structures render the images impossible to experience as mere content. While his biography is necessarily referenced in every elevator pitch about his work, what the artist is opening us to doesn’t fit into a quick story about his life or even the elevator shaft. There is potential for a vast contemplation about the human experience inside each one of these paintings, but it asks for a focused search that is in short supply within the mirror world. With these works, however, we have an opportunity. Like a long take in a 20th-century film, a deeper feeling waits for the pilgrim looking to come unstuck from time. To achieve it, we are asked to wade slowly into these gyres of shadow and light, discover our relationship to each narrative possibility we are given within the picture, and gradually build those possibilities toward a real experience.

Ali BANISADR: The Fortune Teller

Perrotin Gallery, Shanghai

November 6 – December 21, 2024