Siah Armajani is a major public artist, someone whose public sculpture deserves the highest praise. He is a prolific artist, as the much more than one hundred objects in the Met Breuer show, “Follow This Line,” attest. Unfortunately, the exhibition on Madison Avenue does not convey the instant excitement we feel even in the face of the public art slides on view at the show (they are only pictures, but, even so, they convey the architectural magic of Armajani’s work sited in different cities). The Met Breuer has been putting on some of the most interesting exhibitions in New York for a few years now, and it should be praised for paying attention to an artist who is such an active–and political–creative inventor. But there is too much to see, crowded into a single floor of the building. Additionally, these mostly small works–the major exceptions are the remarkable calligraphy drawings that stretch a good length along the gallery walls–end up feeling repetitive and seemingly too emulative of each other, when they well may be not. Usually, the installations at the Met Breuer are sparser and enable its audience to study the work with greater perception. But here one is overwhelmed by numbers–or at least I was.

Armajani has always been taken with politics. The earliest works shown, as we see in Dictionary of Numbers and Fairytale (both from 1958), concerns the Shah’s regime, and are filled with political writing and arcane symbols referring to the problems. It is interesting to see how he has continued his penchant for social commentary; one piece in the show, dedicated to Henry David Thoreau, America’s great nature writer, calls him our “first anarchist.” Armajani clearly is a man of considerable public assertion, and his voice re-establishes a moral base for art–a point of view we find lacking now in American artworks. Like many outstanding artists who have left their homes to establish lives and careers in the United States, his success is based at least in part on the discipline he brought along with him from his origins. Not all of the work addresses politics, but he has a decided tendency to pronounce on issues through the public application of his creativity. At the same time, some of his most strongly contemporary works go back historically to ancient times–as happens in the remarkable large calligraphic drawings that sometimes incorporate simple realist imagery like houses. Even if we don’t understand the Farsi he uses and whose forms he seems to abstract, at the same time the black patterning on white looks sufficiently different for us to appreciate its nonobjective impact. These are finished pieces, notably tied to the artist’s personal and historical past, even if his overall compositions in these large fields convince us that we are looking at contemporary art.

Less compelling, if not less achieved, are the groups of small sculptures, mostly in wood and architecturally driven. Arranged so that they form small.

Assemblies, they are striking models and maquettes in their own right, although their completion in a greater size would lend them the massive gravitas found in the very large public structures Armajani has had built. But Open Porch (no date) and Door Between Windows (no date), nearly like dollhouse furniture in their diminished size, looks like footnotes to a greater achievement and fail to fully encompass their purpose as art. One can appreciate the skill that went into their making, but a larger picture, literally and figuratively, would have weighted the works in the direction of greater range and commitment. (But that statement can be challenged. In contemporary art, size trumps almost everything, but subtlety is lost–and Armajani is a sculptor of remarkable subtlety.) And the problem of there being too many objects doesn’t go away–vitrines and waist-high presentation tables clutter the space, with the additional difficulty of Armajani’s audience being unable to concentrate on so many small works of art. One doesn’t see the show so much as study it, although we do remember that there is a scholarly bookishness to much of the small work.

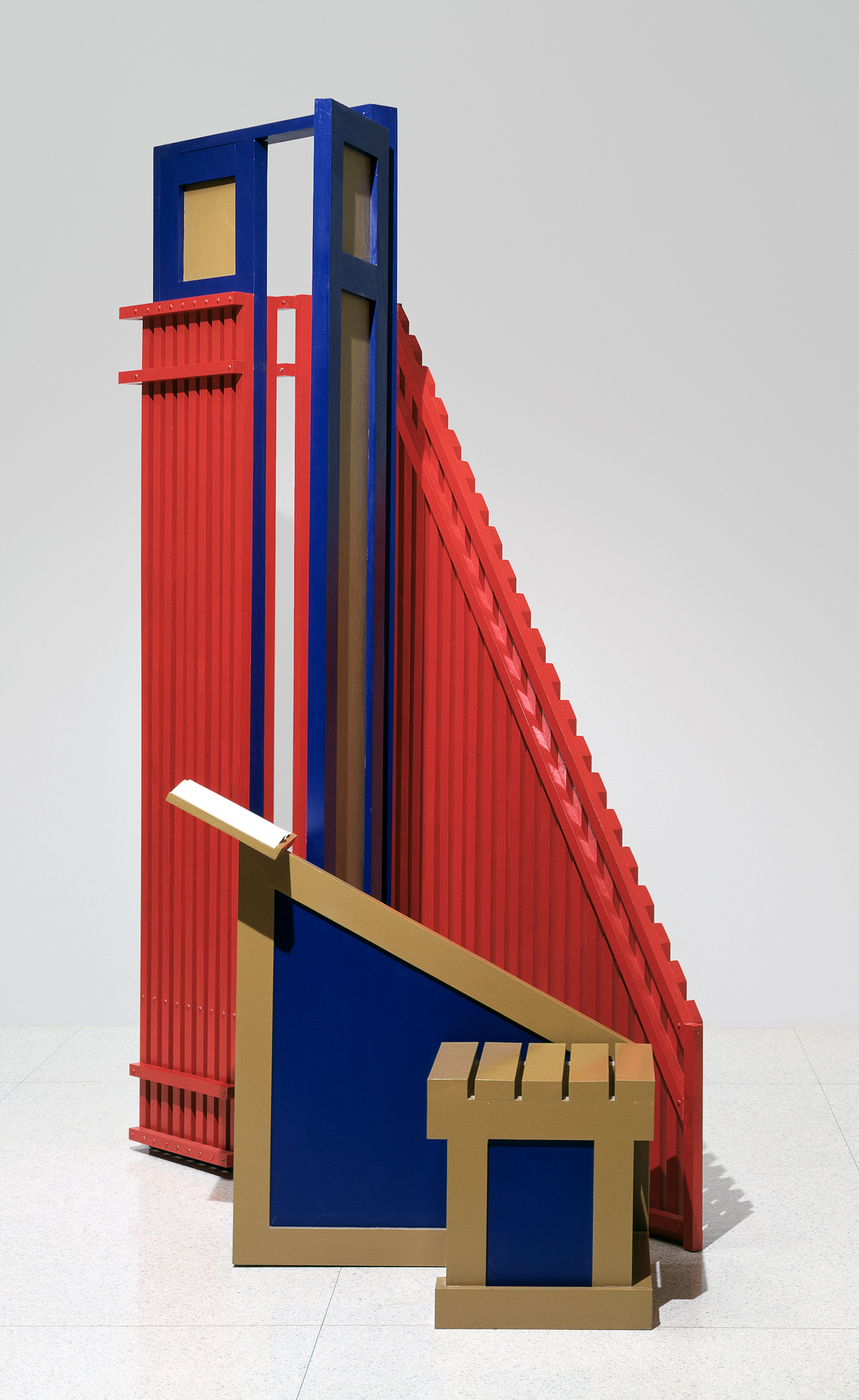

Nearly eighty, Armajani needs now to be seen in light of his impressively varied output, which ranges from the diminutive to the epically sized. The latter is not present much at all in the show; we do see the work called The

Dictionary for Building: The Garden Gate (1982-83), a slightly larger than human size wooden work, which establishes an ascending presence by means of a number of red and blue panels, with a sharply angled gate-like series of slats. A stool connected to the work sits on the floor, with a reader’s pedestal in front of it. It offers the architectural language the artist handles so well in bigger works of art. Often in Armajani’s work there is the need to move around the artwork, and this is the case in the work just described. This happens especially when, as occurs regularly in much of the sculptor’s work, sculpture meets architecture. Armajani’s emphasis on the latter also pushes him toward a highly social vision, in which the politics of democracy are supported by the candor and directness of his thinking. The problem is how to make this known in a show, which seeks to describe rather than enact the point of view an artist like Armajani is taking. Of course, such an attitude is learned rather than artistic; those of us who have encountered his larger bridges–the smaller, wooden maquettes are available in the exhibition–know that the physical action needed to encounter the sculptures mimics the social action he silently prescribes.

The question of social awareness in art has been split between excessively personal regard–the identity art that is so popular now–and social abstractions, work stemming from Joseph Beuys, which leaves very little trace of the human. Armajani, thankfully, is somewhere in the middle. Architecture and sculpture lose their effectiveness if they gravitate toward a monumentality that disregards the size of human presence. One senses that this never happens in Armajani’s art. In the smaller models, part of the sequence entitled “Dictionary for Building,” the language of a responsible architecture, expressed here on a sculptural level, is being developed in a remarkably varying fashion. Windows and stairs are ubiquitous; there is even a sense of humor in the miniature organization of components. At the same time, we realize that these works of art are formally cognizant of the very big public structures. I still question the installation, which is unusually busy; on the other hand, the many objects on view give viewers the chance to see a mind in action. Sometimes, though, the works simply don’t succeed–for example, the computer drawings, done around 1970, incorporate white numbers on black paper. They don’t survive the infancy of this technology and seem arbitrary and artificial. One senses that, in the best work, which is very good indeed, Armajani is working out an idiom that begins in the far-lost past and moves very much into the present. One also intuits that he is determined not to give up the political perceptions that caused him to reject his country. This decision is found in his perceptive literary allusions to Americans in his titles.

It is strange that a foreign-born artist would be the person keeping alive a radical understanding of American democracy, but Armajani has done just that. American art is increasingly in the hands of big money, and it needs exactly the corrective Armajani provides. Sculpture, never easily hung over a sofa, has been pushed to the margins. Yet it is the oldest of the arts. The slide presentation of Armajani’s public work made it clear just how gifted a practitioner of large-scale works he is. In piece after piece, the art demonstrated an uncanny ability to fit into a physical scale that somehow remains sculptural even as it participates in the lives of people making their way across streets, into buildings, or up stairs. These are the structures of public life, and Armajani understands their function instinctively. It is impossible in a show like this to communicate their grandeur as structures; they are huge, outdoor endeavors. But that is hardly the fault of the assiduous curators, who have endeavored to give us almost everything else. This show is needed badly; somehow, Armajani has been slightly under the radar–maybe because he still lives in Minnesota. The political populism of that state has not been lost on him; he shows us a language that communicates well to everyone, as sculpture should. This does not mean, though, that he is anti-intellectual. The work is too precise and too deeply sited for us to call his point of view random or merely an amalgamation of discrete objects. He has a unified point of view.

So Armajani’s ability to move from one culture–one very different from our own–into circumstances like ours results in an art that is freer than usual from the influences his audience might expect from him. Yes, the early work is fraught with references to Iran, and yes, calligraphy has played a role in the art he made in America. But he seems to have found himself as a vehicle for a kind of American thinking we don’t see much here anymore. Contemporary art has lost its sense of place among an overcrowded populace, absurd ambition, and an obsession of money. These are major problems, but neither can we return to a Renaissance humanism–this is not possible. Visionary tactics cannot be sustained by a group, only by individuals like Armajani. He remembers a time when the American dream was not driven only by materialism. He remembers a time when great American writers and thinkers were working out the structure and consequences of democracy, in a pure sense. There is no reason why we cannot return to such an idealism; Armajani’s point of view takes us to a place where good art adumbrates a social sensitivity that borders on the inspired–even if “Follow This Line” does not fully explain the breadth of his vision. It is important to note that the artist is not an easy populist; that his work remains in the forefront of intellectual intelligence and difficult commitment. Armajani is so good that he communicates this vision even in the small works on view. We can only praise his determination and moral persistence at a time when these qualities seem lost.

Writing via press release and photographs courtesy of Siah Armajani at the Met Breuer.