A large group show, mostly of sculptures, curated by China-born, New York -based art consultant Lily Candler, “Sculptor Dimensions” may have been conceived here in New York, but was actually shown in Jingdezhen, a city bordering Anhui in the north. The show, supported by the China Central Academy of Fine Arts, the China Sculpture Research Center, and the Jingdezhen Ceramic Cultural Tourist Group, clearly had been given support from the highest Chinese auspices, who hoped, as they tend to do, to make of this grouping of fifteen artists (eight Chinese artists and seven American artists) a highly regarded composite of Sino-American art relations. Shows like these tend to get buried under official good will, but Candler, who has years of experience with both Chinese and American artists, was able to make the best of the very good art she had at hand. Sculpture, still the poor relative at the family dinner party, deserves more than a cursory glance. It is, as a medium, a major leader of innovation, especially now, when painting seems to have reached an impasse. But the implications of the show are greater than a dedicated social event. It is an exercise in bringing about cultural fulfillment, in which artists from both worlds mingle and merge, finding affinities in artistic places and objects not usually thought of as conducive to cultural connectedness.

A large group show, mostly of sculptures, curated by China-born, New York -based art consultant Lily Candler, “Sculptor Dimensions” may have been conceived here in New York, but was actually shown in Jingdezhen, a city bordering Anhui in the north. The show, supported by the China Central Academy of Fine Arts, the China Sculpture Research Center, and the Jingdezhen Ceramic Cultural Tourist Group, clearly had been given support from the highest Chinese auspices, who hoped, as they tend to do, to make of this grouping of fifteen artists (eight Chinese artists and seven American artists) a highly regarded composite of Sino-American art relations. Shows like these tend to get buried under official good will, but Candler, who has years of experience with both Chinese and American artists, was able to make the best of the very good art she had at hand. Sculpture, still the poor relative at the family dinner party, deserves more than a cursory glance. It is, as a medium, a major leader of innovation, especially now, when painting seems to have reached an impasse. But the implications of the show are greater than a dedicated social event. It is an exercise in bringing about cultural fulfillment, in which artists from both worlds mingle and merge, finding affinities in artistic places and objects not usually thought of as conducive to cultural connectedness.

Actually, these kinds of shows take place often in China, usually under the umbrella of the participating governments and academic centers. China is nothing if not determined to present its cultural openness, evidence of an equally open political process, although Ai WeiWei’s story and those of other artists not so well known indicate something else. In any case, whatever the motives for the Chinese acceptance of the show, it is clear Candler showed the artists very well and to everyone’s advantage. Perhaps not as highly esteemed as painting in Chinese art history, sculptures from the start nonetheless were used to perform rituals and embody esoteric knowledge still not fully understood by scholars. The point remains, though, that it has never truly lost its memorializing function as art. Even in Beijing, there are huge government-supported spaces for life-size Marquette’s of grand memorial sculptures—say, a war memorial—to be worked on in preparation for the actual piece. Unfortunately, art of this kind tends to be impersonal and grandiose, the very opposite of taste in sculpture today (and, we can say, in direct contrast to the best of Chinese classical sculpture). But thanks to Candler’s sharp eye, a group of highly talented, socially engaged sculptors were able to present work more or less figurative in design; the sculptures were beautifully made and incorporated a melancholy that felt as ancient as it was new. The elegiac twist, a transparent longing for a better time, is what makes much of the work feel contemporary.

The age-old penchant for edification, even didacticism in Chinese art was present. You can see this in the severe female figures by Li Zhan, whose bodies, usually truncated in the waist, often emanate a melancholy restraint that suggests a classical reading, although this would be hard to prove. But their gravitas is not to be denied. As figurative carvings in wood, these cultures are remarkably good; their reserved, somber presence actually intimates both feelings and a way of behaving most of the world has long rejected. In Don’t Say Goodbye (2014), which is roughly 80 inches high, a woman in a dark red dress with a blank gaze and an emotionless expression, returns our interest in the starkest terms. Her hands are in a strange position in relation to her body. One hand, brought up against her chest, contorts itself in an ungainly fashion. The other hand, wide open, holds its pose at the side of the woman’s body. The work is an exercise in self-sufficient idiosyncrasy, but the eccentricity is neither self-involved nor aggressive; instead, it speaks to that small bit of strangeness we all carry within us, but disguise by following acceptable behaviors. Li Zhan is an outstanding sculptor, someone capable of developing an attitude at a far remove from the expressionistic enthusiasm that characterizes modern life. Even if the work is not consciously classical, something of its restraint has entered into the life of the figures, giving them a dignity we don’t often see in contemporary art.

The age-old penchant for edification, even didacticism in Chinese art was present. You can see this in the severe female figures by Li Zhan, whose bodies, usually truncated in the waist, often emanate a melancholy restraint that suggests a classical reading, although this would be hard to prove. But their gravitas is not to be denied. As figurative carvings in wood, these cultures are remarkably good; their reserved, somber presence actually intimates both feelings and a way of behaving most of the world has long rejected. In Don’t Say Goodbye (2014), which is roughly 80 inches high, a woman in a dark red dress with a blank gaze and an emotionless expression, returns our interest in the starkest terms. Her hands are in a strange position in relation to her body. One hand, brought up against her chest, contorts itself in an ungainly fashion. The other hand, wide open, holds its pose at the side of the woman’s body. The work is an exercise in self-sufficient idiosyncrasy, but the eccentricity is neither self-involved nor aggressive; instead, it speaks to that small bit of strangeness we all carry within us, but disguise by following acceptable behaviors. Li Zhan is an outstanding sculptor, someone capable of developing an attitude at a far remove from the expressionistic enthusiasm that characterizes modern life. Even if the work is not consciously classical, something of its restraint has entered into the life of the figures, giving them a dignity we don’t often see in contemporary art.

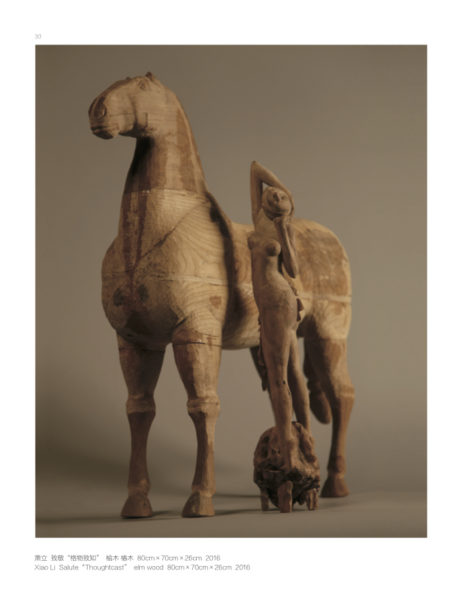

The extraordinary wooden carvings by Xiao Li also intimate the past, both in their atmosphere and their facture, an ongoing interest in classical Chinese sculpture. It is impossible to describe the aura of an art object, but the artist does make decisions whose consequences resonate in unspoken ways. In Thoughtcast (2016) a broad-chested horse with cropped ears stands upright, in proud if anonymous demeanor. Its outlines are exquisite; it is composed of elm wood. Standing next to the horse is a naked woman, whose feet rest on some sort of strange rock-like ball. The woman’s hands cradle her face, which exists at a bizarre angle—it is as if her head had been turned upside down. This bit of eccentricity, coupled with the extraordinary beauty of the horse, results in a classical tableau with the equivalent of a small crack, in the form of the nude woman’s awkward presence, undermining the work’s historical dignity and presence. Such a reading is perhaps inevitable, given the current need to find flaws, deep ones at that, in the sublime. As the two sculptors show, it is possible—extremely difficult but possible—to revive forms and feelings we associate with China’s classical past. A few individuals may not translate into a movement, but the point is clear: art follows a linear history, but our experience of it is immediate and ahistorical and filled with surprise. The moment outlasts the legacy.

The extraordinary wooden carvings by Xiao Li also intimate the past, both in their atmosphere and their facture, an ongoing interest in classical Chinese sculpture. It is impossible to describe the aura of an art object, but the artist does make decisions whose consequences resonate in unspoken ways. In Thoughtcast (2016) a broad-chested horse with cropped ears stands upright, in proud if anonymous demeanor. Its outlines are exquisite; it is composed of elm wood. Standing next to the horse is a naked woman, whose feet rest on some sort of strange rock-like ball. The woman’s hands cradle her face, which exists at a bizarre angle—it is as if her head had been turned upside down. This bit of eccentricity, coupled with the extraordinary beauty of the horse, results in a classical tableau with the equivalent of a small crack, in the form of the nude woman’s awkward presence, undermining the work’s historical dignity and presence. Such a reading is perhaps inevitable, given the current need to find flaws, deep ones at that, in the sublime. As the two sculptors show, it is possible—extremely difficult but possible—to revive forms and feelings we associate with China’s classical past. A few individuals may not translate into a movement, but the point is clear: art follows a linear history, but our experience of it is immediate and ahistorical and filled with surprise. The moment outlasts the legacy.

Serena Bocchino is best known for her abstract expressionist drawings and paintings, but for this show she included two sculptures, both made of wire and clay and wood. Soundbox (2016) is an open square held up by a single support rising from a pedestal; inside the square are a series of abstract painterly gestures rendered in three-dimensions. Soundbox thus is a sculpture that is actually more of a painting. The American esthetic in sculpture could not be more different from the ideas inspiring Chinese three-dimensional art. It is expressive, concerned with energy and freedom, and takes little interest in what precedes it. Bocchino belongs to a generation relatively close in time to the first practitioners of the New York School, so her style relies in on a combination of verve and emotional intensity. In Soundbox, whose overall outlook reminds us pretty closely of David Smith’s landscapes set up within a frame, the artist uses sculpture to idealize the major legacy abstract expressionism has become. But it is not merely a homage; it is also a glowing work in its own right. The plastic effectiveness of the work shows us that it really doesn’t matter from which period we borrow, near or far away. But we must transform our appropriation into something new.

Chakaya Booker, a black artist long established in the American art world, offered a ribbon like, untitled piece made in 2012. Constructed from tires and braced by wood, the work has a lyric grace that begins with and then extends beyond its urban materials. Booker’s ongoing usage of the rubber has resulted in a considerable facility based on an entirely urban outlook. There is no direct reference to black American experience, but the used rubber, a fall-out of driving and city life, is so persuasively an urban element that we quickly identify it as part of African-American arts. The color of the rubber, inexorably black, also refers to Booker’s culture.

American painter Nola Zirin is best known for her painterly abstractions, but for this show she offered Detroit Debris (2017), a series of found objects covered with an enamel gold spray supported by a flat pedestal. A homage to the bizarre attraction of kitsch, Detroit Debris establishes a highly sculptural space, with parts of hardly recognizable objects jutting out from the main core of the sculpture. One thinks a bit of John Chamberlain’s car parts, soldered together to create new forms, which nonetheless maintain their independence as discrete elements. Zirin, a veteran artist, here moves away from some of the linear discipline we experience in her paintings, establishing instead an object of inspired kitsch, beholden to no audience or movement.

Sculptor Dimensions is too small to serve as an overview, but it is big enough to encourage a few generalizations. For generations now, there has been no particular way to make art. National identifications are gone, and the creeping internationalization of a contemporary art style is firmly established. But that doesn’t mean we are unable to find, here and there, traces of legacies that enliven and even dignify an esthetic dependent on the moment. This is easier to do in China, where the air itself seems weighted with past, than to accomplish in New York, determined as we are to forget everything but the present moment. It is also fair to say these comments are by now the residue of a discussion that has gone on for decades, without real clarity. Candler’s decision to contrast and compare styles and cultures within the medium of sculpture has the achievement of stimulating points of view that hopeful will invest contemporary art with the small bit of the past that it needs. We can not live only in the present or look to the future; sometimes looking backwards enables us to see clearly again. Sculpture, the oldest of the arts, can be seen as an object entirely free of influence or, more truthfully, as a work inevitably laden with previous efforts. It makes sense that we acknowledge the validity of both.

Sculptor Dimensions is too small to serve as an overview, but it is big enough to encourage a few generalizations. For generations now, there has been no particular way to make art. National identifications are gone, and the creeping internationalization of a contemporary art style is firmly established. But that doesn’t mean we are unable to find, here and there, traces of legacies that enliven and even dignify an esthetic dependent on the moment. This is easier to do in China, where the air itself seems weighted with past, than to accomplish in New York, determined as we are to forget everything but the present moment. It is also fair to say these comments are by now the residue of a discussion that has gone on for decades, without real clarity. Candler’s decision to contrast and compare styles and cultures within the medium of sculpture has the achievement of stimulating points of view that hopeful will invest contemporary art with the small bit of the past that it needs. We can not live only in the present or look to the future; sometimes looking backwards enables us to see clearly again. Sculpture, the oldest of the arts, can be seen as an object entirely free of influence or, more truthfully, as a work inevitably laden with previous efforts. It makes sense that we acknowledge the validity of both.

-Jonathan Goodman

photographs provided by the gallery