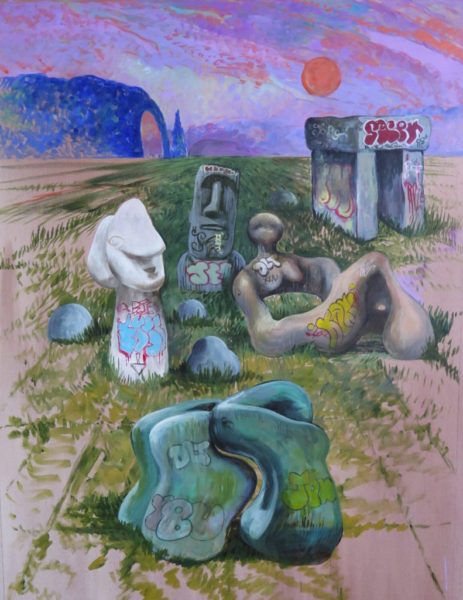

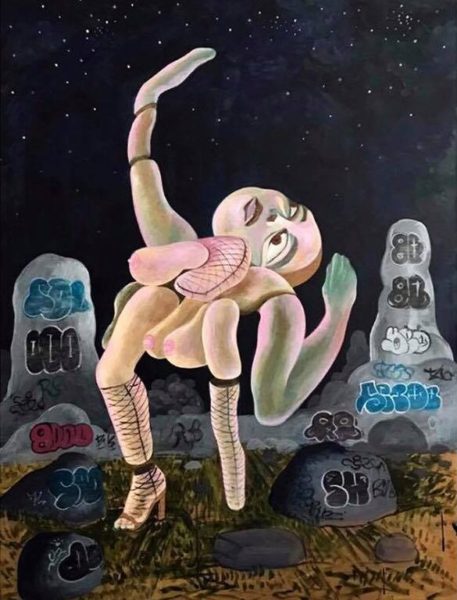

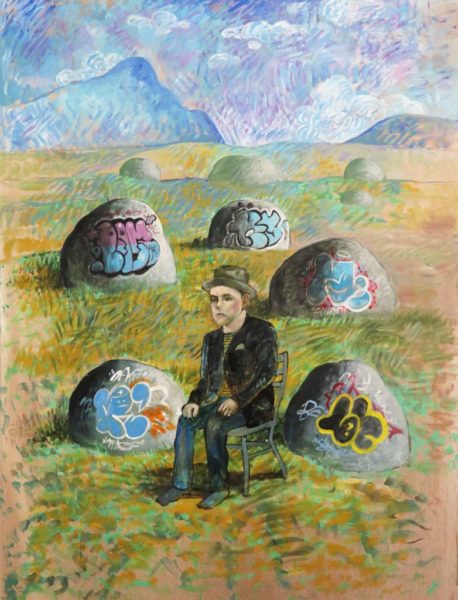

Founder of Whitehot Magazine, painter, and accomplished saxophonist, Noah Becker is an enigmatic figure within the contemporary art world. From his modest roots, growing up on a forty-acre farm off the coast of British Columbia, Becker has subsequently achieved recognition as a cultural generator. Stepping into the artist’s Brooklyn-based studio it’s hard to anticipate what to expect as his paintings have a tendency to reinvent themselves every few years. Diaphanous layers of paint, deliberate mark making, and the omnipresence of the human form are the only true constants within Becker’s ever-evolving work. Recently, works in progress depicting desolate patchy fields punctuated with graffitied boulders, lone figures, and families posing for selfies have cropped up on Becker’s Instagram. These new works continue to demonstrate Becker’s deep appreciation for the history of painting via the inclusion of impressionistic skies, Henry Moore-esque rock formations, and surreal juxtapositions of figures within uncanny landscapes. Arte Fuse had the opportunity to sit down with Becker in his studio and explore this newest body of work as well as his journey through the New York art world.

Katie Hector: Noah thanks for having us in your studio. Let’s start off and discuss the series of paintings you currently have in the works. The imagery you’re using gives the impression of being deeply personal. Is this the case? If not, where are you sourcing your subject matter from?

Noah Becker: I saw a photo of Picasso wearing a cowboy hat and holding a pistol. Apparently, when studio visitors would ask Picasso what his work was about, he would put on the cowboy hat and fire blanks at them. This got me thinking about making my paintings about nothing – a really STRONG nothing.

KH: Does this series of paintings have a working title?

NB: Landscape. It’s a very generic kind of title but I’m using the landscape as a gallery space to “install” various things within.

KH: Can you explain what prompted the transition from your previous body of work to this series?

NB: I get bored and like to change ideas from series to series. I consider the ability to change a mode which allows me to continue making forever. I guess it’s an attempt at containing my ideas in a format and making something ongoing and perpetual.

KH: Walk me through your process. Do you typically sketch and plot out a painting or sections of a painting beforehand or do you work directly onto the canvas?

NB: I have a Landscape in mind as a space for things to be placed. I think about it as a space to install things, more like an installation and less like a painting. I usually draw the figure or something then add the background. Sometimes, like Nicole Eisenman, I’ll set the scene first but I tend to go by Delacroix’s methods which require adding the scene after.

KH: You have a deep appreciation for the history of painting and tend to reference old masters within a number of your paintings, especially Valåsquez. Do you remember the first time you saw one of his painting? Was it in person or a reproduction?

NB: I saw the first one in an HW Jansen art history book and I’ve copied a lot of different paintings since. Someone suggested I copy Velasquez, so I did. After copying ten Velasquez paintings something just clicked.

KH: Perusing your CV it seems as though Canada embraces your work with exhibition opportunities. How has their support shaped your practice? Do you have many ties to Canada considering your practice is based in New York City?

NB: Canada has an art system that recycles young artists under 40. Once you’re too old for the Sobey Award then you are expected to get Canada Council Grants. It’s a small scene in Canada and a Canadian artist who goes to the US is mostly taken out of the art system there. At the time Canada was very good to me and awarded me many museum shows and prizes.

KH: You were able to circumvent institutional academia, a system of pedagogy which many up-and-coming artists subscribe to. How did you self-educate and build the foundation of your practice growing up?

NB: Francis Bacon was my painting idol and Charlie Parker for saxophone. I started Whitehot Magazine Of Contemporary Art. That turned out to be educational after publishing 6500 articles and 500+ writers. I had to do something drastic in my situation and I got lucky because my magazine connected with the paradigm shift of people not reading print and getting info online. After I launched it in 2005 social media started to happen and raised it further.

KH: As the founder of Whitehot Magazine you evidently sensed a gap in contemporary art criticism, what was the impetus behind forming Whitehot Magazine?

NB: I had a near nervous breakdown and decided to start a magazine. It became a real magazine but I never expected that. So at a certain point, I just went with it. It took a lot of bravery to step out into the public eye like that.

KH: I read in several places that you experienced tragedy at an early age in the form of a fire which consumed your familial home. Firstly, were you or any other family member hurt in the fire? Has the understanding of loss fundamentally impacted you or your work in any way?

NB: My father died last January which marks my most recent loss. The fire framed my daily emotional state. All my early paintings and my first saxophone burned in the fire but no one was hurt. I feel like things really changed after that traumatizing event.

KH: You are also an accomplished saxophonist. What type of saxophone do you play and who are some of your musical influences?

NB: I practice the saxophone daily so yes. I play a Martin Magna Alto from 1952, with a vintage Selmer C* soloist mouthpiece. I like JS Bach, Bartok, Hindemith, Debussy, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane and the friends I’ve played with.

KH: You mentioned in an earlier interview with Arte Fuse, “it took me forever to become social and learn the pecking order of city people.” Can you speak more to this? Having lived and thrived in New York City for a number of years what advice would you give your past self?

NB: After growing up in rural Canada and being homeschooled it was a challenge to get along in a cosmopolitan environment. We regenerate all the cells in our bodies every seven years. I’m not in touch with my former self, I’m more in the moment.

KH: Thank you for taking the time to chat with us, Noah.

His website is here.