Nari Ward’s art is as unique and imaginative as it is tied to the things we use and encounter daily. Instinctively understanding the power of recontextualizing and spotlighting what is most commonplace, Ward builds perspective and compelling social commentary with New Yorkers’ discarded objects. Interwoven throughout his work, is the experience of black people in America.

“Nari Ward: We the People” spans several floors of the New Museum, granting viewers a good amount of space to walk around Ward’s large-scale works and think a little between them.

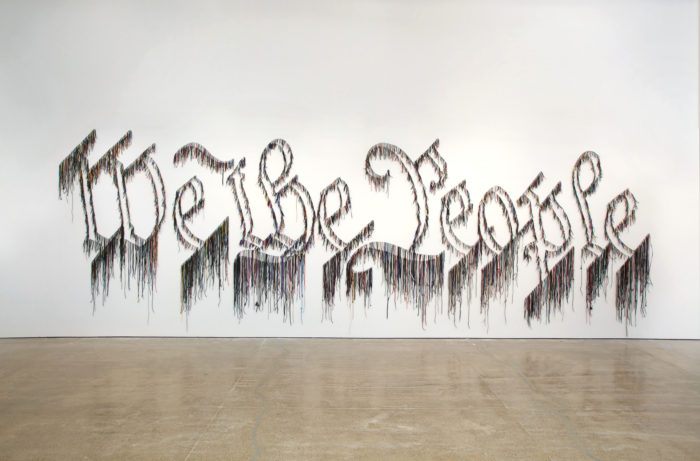

As the elevator doors open to the third floor, the viewer is met with the piece for which the exhibition is named. “We the People” (2011) is made up of numerous shoelaces in a variety of bright colors, cut to a variety of lengths, which, pushed into a single surface, together spell out the first three words of the U.S. Constitution.

Inspired by the New York custom of throwing knotted-together sneakers over city power lines, “We the People” brings to the three words it spells that which was originally left out of them — things like color and inequality. As Ward recreates the words, he seems to correct a fundamental error in the writing of our constitution, recognizing and empowering those who were once invisible.

Nari Ward: We the People at the New Museum. Installation view courtesy of the New Museum.

Nari Ward: We the People at the New Museum. Installation view courtesy of the New Museum.

On a wall to the right hang two pieces from Ward’s “Breathing Panel” series (2015 – ongoing). These copper panels bear holes that make up symbols known as Kongo cosmograms. The Kongo cosmogram — here formed by a cross within a diamond — represents the four moments of the sun as it continually cycles through the worlds of the living and the dead.

Ward first saw these symbols cut into the floorboarding of the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia. The church, founded by formerly enslaved people in the 18th Century, was an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and the symbols served as breathing holes for runaway slaves who were forced to take refuge under the floorboards.

One breathing panel is marked subtly by an array of footprints which bring to mind the feet of fleeing slaves. It can be noted that, traditionally, the cosmogram may also be drawn into the dirt and stood upon while taking important oaths before the living and the dead in the underworld below; making the hiding spot at the First African Baptist Church a particularly profound and somewhat chilling sight.

Made of the same metal as Lincoln’s penny and marked by symbols linked not only to African spirituality, but to Christianity and wealth, these pieces are not only beautiful but rich with cross-cultural imagery, meaning and memory.

On the second floor, “Hunger Cradle” (1996) spans an entire hallway from floor to ceiling, creating a system of multicolored yarn and rope that the viewer may walk through like a tunnel. Sewn up in this cradle are discarded objects that Ward has been collecting since the piece was first exhibited at a run-down firehouse in Harlem. This venue served as the work’s first source of materials and today serves as Ward’s own studio space.

In an interview with Ocula earlier this year, Ward stated that “Hunger Cradle” is tied to two seemingly opposed concepts: “devouring” and “protection.” It sucks up things around it. It also safeguards these unwanted things from such forces of destruction as gentrification. Its organic intricacies may also remind the viewer of neural networks where these caught-up objects — a soccer ball, a radiator, a piece of outdated computer equipment — are like memories collected and protected over time.

Around the corner is “Amazing Grace” (1993), an arresting multimedia work that takes up an entire room. At the center of the piece lies a heap of discarded baby strollers bound together with firehosing. Additional pieces of flattened hose form two substantial pathways that curve around this pile and meet at either end. Beyond the outer edge of each pathway stand many more vacant, discarded baby strollers, neatly organized into rows. Shaped like a large oval, “Amazing Grace” is comprised of nearly 300 strollers. Mahalia Jackson’s rendition of the hymn from which the title takes its name rises above the dimly lit scene and can be heard throughout the floor.

For those unfamiliar with New York City in the ‘90s, it is important to mention those baby strollers, once thrown away, were often taken up and repurposed by the homeless who used them to cart their belongings. In addition to homelessness, the 90s saw swelling AIDS and drug epidemics devastating communities, especially communities of color like Harlem where Ward created this work. With a shape Ward has likened to a womb, “Amazing Grace” evokes a profound sense of loss which speaks to the devastation that surrounded him.

Many have noted that the piece’s shape is similar to that of a ship as well. Walking the uneven, makeshift pathways, the viewer is left with a kind of unsure footing akin to walking the deck of a ship at sea. Surrounded by neatly arranged rows of objects representative of the innocent and the homeless, it takes just a small step to see oneself standing aboard a slave ship.

Nari Ward’s gift is his ability to speak profoundly to anyone and everyone using a combination of skilled labor and an alphabet made up of the very objects we see every day. While he received formal training at both Hunter College and Brooklyn College, studying closely under William T Williams at the latter, it can be said that Ward’s most influential professor and unending inspiration is the New York City neighborhood of Harlem. Here is where he sourced his first materials. Here is where he listens to the streets. Here is where he became an artist and continues to develop his art.

Nari Ward: We the People

February 13 – May 26, 2019

New Museum

235 Bowery,

New York, NY 10002

Images courtesy of the New Museum and the artist.