In a noble–and necessary–effort to bring women and neglected artists of color into the mainstream from the margins that had previously been their fate, Galerie Lelong is showing the colorful, exuberant, and well-considered paintings of Mildred Thompson (1936-2003). Thompson from the start was an anomaly–an independent woman who left her country of origin for Germany largely because of the neglect and prejudice she experienced at home. A graduate of Howard University in 1957, Thompson also studied at Skowhegan in Maine and at the Brooklyn Museum School, moving to Hamburg to take courses at the Hochschule fuer Bildende Kuenste from 1958 to 1961. Living in Germany for most of the 1960s and ‘70s, Thompson moved back to the United States at the end of the ‘70s, dividing her time between Washington, D.C. and Paris from 1979 to 1985. In 1985, Thompson located to Atlanta, where she would spend the rest of her life. Her activities in Atlanta included editing writing for Art Papers and teaching at three schools: Spelman College, Agnes Scott College, and the Atlanta College of Art.

The show’s long title–”Radiation Explorations and Magnetic Fields: Paintings by Mildred Thompson since the Early 1990s”–indicates the artist’s long-standing interest in science. The first part of the title refers to two major series brought about by Thompson, much of whose work poetically explored the visual consequences of scientific events. Her oils on canvas document, without closely following, the long march of increased knowledge about physics, whose theoreticians recently have resorted more and more to language that seems, at least to the reader unfamiliar with the filed, like poetry leaning toward abstraction! It is likely that Thompson felt the same way, for her canvases radiate intellectual interest and what looks like a command of the scientific work being done while she was active as an artist. But we must remember that the images never revert to mere illustrations; rather, they are lyric interpretations of a reality that is certainly real enough but far beyond human visual capability. While fine art has in fact intuitively recorded scientific events, Thompson’s paintings seem especially tied to a close understanding of the physics she studied and read as an adult artist.

The results of Thompson’s studies are impressive. Radiations Explorations 8 (1994), a large oil on canvas, looks like a modernist re-interpretation of a late painting by van Gogh, in which the elements of nature appear to be in flux, seemingly at sea in a vast ocean of space. This painting expresses itself in a loosely constructed whorl in white, achieved by white curving lines and spheres. The open, whirling imagery occurs in the center of the composition, which is filled with smaller dots, of various colors, that echo the larger white orbs that dominate the central space. Red lines and yellow spheres occur on the edges of the painting, which presents a freely flowing nonobjective imagery that exists as movement. Viewers experience this kind of abstract motion on a regular basis in Thompson’s art, whose chief characteristic and most attractive element is its willingness to maintain a colorful flux. It can also be said that this flux, while suggestive of starry skies and physics events, is finally an abstraction and not a portrayal of the world, except on the most abstract terms. Thompson’s orientation toward pure patterns and designs are of course helped by the now-established history of painterly abstraction, but she makes the legacy her own in colorful, freely moving art.

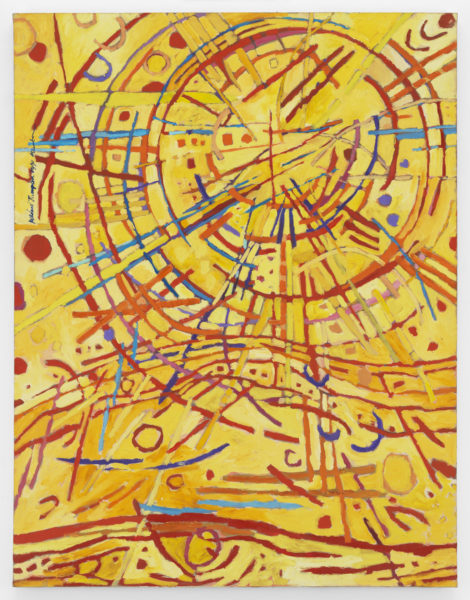

Magnetic Fields (1990) is a beautiful painting documenting a field of energy flowing outward from an oulined circle occurring at the top of the composition. The paintings in this series occur on a yellow backdrop, with their imagery mostly expressed though gently curving lines. The image in this particular painting exists as a kind of sunburst, with rays echoing outward, away from the open orb’s center. The magnetic field here is an open system, but one actual in reality, in which invisible energy and systems are rendered discernible as innately attractive patterns. It looks very much like Thompson is demonstrating the existence of worlds which surround us, but which we cannot see. She is not calling into question the reality of magnetic fields; instead, she is portraying the invisible as something palpable. This is a choice based on intuition, even if its truth is a scientific reality. But despite the objectivity of its origins, Thompson’s portrayal of the unseen borders on the majestic, for she invests her knowledge of the fields with high lyric feeling. This painting, and others in the series, are notable for their bright yellow background–this color is close to harsh, but it also somehow seems like an excellent curtain for the very exciting occurrences being laid out for us. Thompson is a gifted improviser here and throughout the body of her work.

The last image discussed here, Hysteresis III (1991), is a pastel on paper, one of a distinguished group on show. The term “hysteresis,” difficult to briefly explain, refers, according to the dictionary, to a lagging in magnetic values when the magnetic field has been altered by a previous event. Given the complexity of the idea, it is best simply to meet the image as it is, without attempting a sophisticated understanding of the science behind it. If we do that, the image is gorgeous, marvelously full of life. Curving red lines circulate across the yellow field on which they occur, with blue lines echoing the movement of the red ones. Small red, orange, and light mauve blotches, either rectangular or spherical dot this nonobjective landscape. It is a piece of pure existential forms, even as it is an artifact visually explaining a complex event. Thompson’s visual poetry and visionary assurance feels more international than American; it belongs to a modernism that feels like it began in Europe. This seems particularly true when we remember that the artist lived in Germany during her formative years as a painter. It is of course true that art stemming from modernism comes from all over the world today–and that, indeed, modernism was international to begin with, when it first took place. It is to Thompson’s credit that the left America for Europe, in search of room to breathe; it is even more interesting to know that her style cannot be read as an idiom particular to a place. Her influences were scientific rather than geographical, resulting in an art of genuine sweep, vision, and complexity.

Mildred Thompson: Radiation Explorations and Magnetic Fields at Galerie Lelong

February 22 – April 21, 2018

528 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10001

-Jonathan Goodman