Born on the edge of Sweden’s Arctic Circle in 1962, Mamma Andersson now lives in Stockholm. But her art, in many ways a continuation of the northern landscape she grew up with, also evokes domestic scenes that refer both to film clips and to personal memories, as well as being influenced by the interior imageries and scenery paintings of Scandinavia’s 19th century. The atmosphere is unabashedly romantic–the title of the show is called “Lost Paradise.” Even so, the roughness of the paint handling and the deliberate visual awkwardness of her scenarios joins her to some of the more expressionist European painting styles we see today. Linking the variety of these efforts is the artist’s wish to convey a beauty only marginally touched by people–a situation that, sadly, is no longer available now. This means that the show hovers somewhere between a backward glance toward paradise and a present gaze toward its loss, both of which refuse to overly romanticize the trees and horses, people and domestic spaces that inhabit her art. Thus, the sadness of Andersson’s present tense is muted by the romance of her memory.

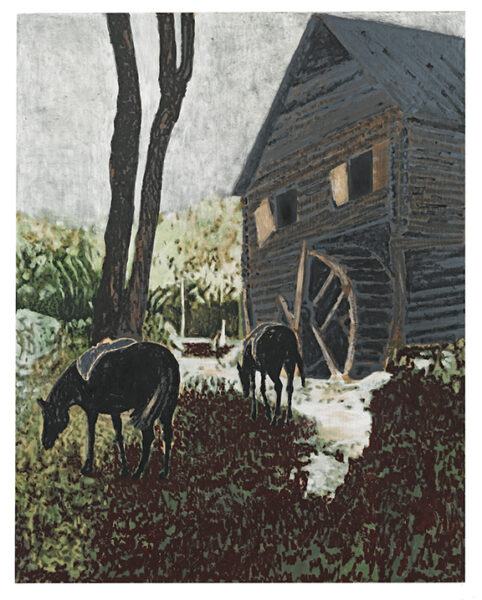

Lull (2019) describes two brown horses grazing on grass and a small section of white water or snow, next to which a mill sits, complete with the turning paddles of a millwheel, meant for creating the energy needed for tasks. The large brown mill, on the right, looms over the painting but no longer seems to be used; opposite, two tree trunks rise into a gray, cloud-dense sky, underneath which is a field of light-green foliage, in contrast with the dark greens that fill the forefront of the painting. The expanse might well be defined as a moment of silence, as indicated by the work’s title, but melancholy exists as well–the quiet sadness of memory infuses the imagery with a sense of loss. In Wood Cut (2019), a large, blasted, leafless trunk rises upward, dominating the painting. It is a deep red, being leafless and with its thick branches cropped so that they resemble stumps rising from the main part of the tree. The dead tree is surrounded behind a small patch of snow, behind a thin line of trees in front of the upward ascent of a mountain. This image is more openly reflective of loss, permeating the painting with a personally felt sense of natural disaster.

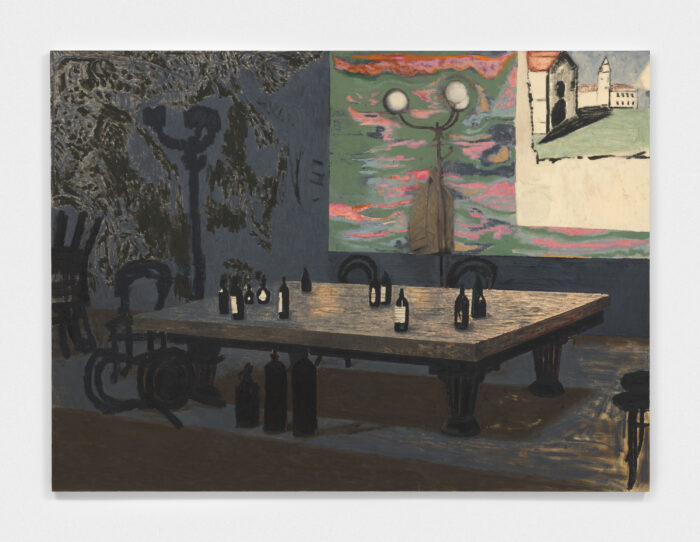

Perhaps the most ambitious, or thematically representative, painting in the show is Andersson’s Last Waltz (2020), in which a low table, maybe in a back room of a bar, has a series of wine bottles standing on it. Three large, bottle-like containers front the table, behind which, on the left, is a hard-to-recognize pattern on the wall. Next to the design is a painting–of a light building in clear daylight and tower existing in a gray plaze, with an art nouveau sea, mostly green but also pink and slate blue, framing the sunlit buildings. The title of the work establishes the notion that this is the image of a party’s end; no person is evident on the site, whose effects tell a tale of recently ended fraternity. Here, as in the other pictures described, Andersson recollects moribund paradises, making the unhappy assertion that we cannot save what is already lost–either in nature or human life. She offers a different point of view, one more humanly sensitive than we might expect here and now, where the intellect and moralizing tend to hold sway in the art world.

Jonathan Goodman