Kit White, a painter of indisputably lyric accomplishment, is currently showing at two venues: FreedmanArt and the Institute of Fine Arts. White, now a mature artist, is a long resident of New York City, where he has practiced a distinctive form of poetic suggestion, in which rickety, skeletal structures occupy the center of the composition, whose surrounds indicate a lonely landscape. Interestingly, though, his efforts do not necessarily derive from the New York School—even though White showed twice with Betty Parsons, a major gallerist of the movement, in the late 1970s. Certainly, he recognizes the fact that the abstract artists working shortly before him filled their paintings with inchoate, nonobjective form, intending to portray the strong emotion resulting from that form. But White is looking not so much for an expressionist intensity as he is interested in communicating a view that derives from a philosophical outlook and earlier history. A reader of contemporary poetry as well as a former student of Latin and Greek, White recognizes a time when culture was slower—a time when the act of painting was mediated by a knowledge of what preceded it, and when poetry was actually read.

The artist has a house, which he built himself, and a studio some two hours north of New York City. This home, along with his townhouse close to the South Street Seaport in Manhattan, gives him a point of view that is both bucolic and urban. Despite his long stay in New York City, the paintings themselves do not strongly orient toward expressionist freedom and willful intensity. Instead, they suggest the effects of both culture and nature. There is the rendering of an austere nature that can be found from one painting to the next, as well as the sense of the beginning of culture, seen in the horizontally aligned, reiterated image of the stick-like palings. White’s paintings are neither entirely figurative nor completely nonobjective. Instead, he balances the two outlooks, so that the composition looks both like an abstracted landscape and like an attempt at constructing a home. But White’s paintings do not only give way to feelings of uncertainty and fragmented insight; they also communicate a calm regard for nature—a point of view clearly seen in the more recent work.

Thus, White’s paintings hover before us, embellishing an image that incorporates several dualities: culture and nature, abstraction and figuration, melancholy and emotional calm. White is not an artist of grand rhetoric; rather, he has invented an image that can sustain stylistic repetition and diverse interpretations. The formal structure of the paintings is significant enough that it bears interest from one work to the next. My own reading is that the compositions tend toward melancholy—a kind of cultural purgatory. But it can just as easily be said that the imagery reflects a willingness to move beyond any particularly pessimistic view. Making a painting is inherently a hopeful activity, and we cannot ascribe White’s art to any easy fatalist vision. We might say that the ambiance of the work is muted; this counterpoints the broad self-absorption of the three best-known painters of his generation: Eric Fischl, David Salle, and Julian Schnabel. In contrast, White’s introspection is clear in his paintings, which communicate not only visual independence but also historical depth.

White distinguishes himself by suggesting emotion. In order to get at feeling, White, who writes professionally as well as paints, has produced a body of work in which intuitive intelligence is key. His esthetics are direct and cultured in a time of casual, often uninformed assertion and indifference to ideas. He is someone who has grown up with nature—in a large farm in West Virginia. And now he has a country home in upstate New York that looks out at woods some distance away. Nature is clearly a means of solace, and appears to be as important to him as art. The paintings suggest a continuing interest in the place of nature today, at a time when the outside world is under fierce attack from industry. In fact, the sticks placed at different angles resemble tangled branches just as much as they intimate a humanly built structure. The ambiguity is part of White’s strength as an artist. And the serial repetition of his basic imagery imposes a plan on what seems to be an intuitively considered point of view. White’s conscious decision to move from a vertical to a horizontal orientation pushes his art in the direction of nature rather than the verticals of cultural constructions—buildings, statues, monuments.

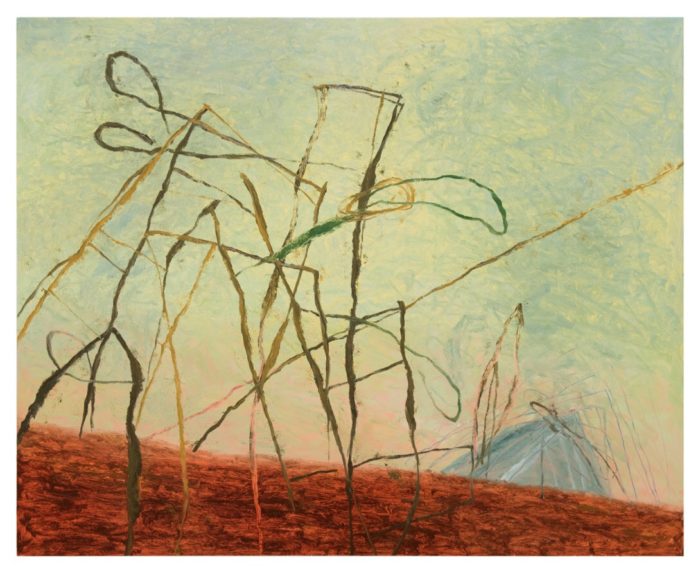

The two shows do not truly comprise a retrospective. Instead, they offer an overview that highlights achievements of particular note over the years. White’s fugue-like variations constitute a reliance on a basic imagery. His success is based on the finely handled reorganization of primary elements: the precariously arranged sticks, the simple ground on which they stand, and the monotone sky standing behind the pieces of wood. In Phalanx (2009), the elements are recognizable from the start: a complex, linear, angled structure that might point to the rendering of a house; a red clay ground; and a pale-green atmosphere behind the transparent structure of the building. It is striking as an image of tentative balance. Additionally, the atmosphere feels otherworldly, seeming to exist in a place outside our sensory knowing. It is hard to say whether this painting or White’s body of work emphasizes desolation. Viewers looking for an existential interpretation can find it well enough. But at the same time, his art reestablishes a connection with nature, an action that is clearly optimistic. White’s appreciation of nature is based upon classical terms, but he is also a very contemporary artist.

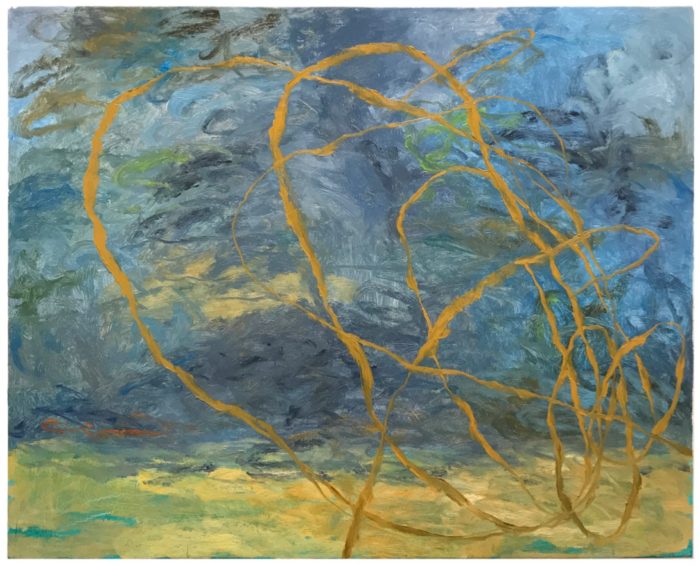

In some ways, the most vigorous paintings on show had to do with rendering a colorful landscape. In Blue Web (2001), the painting is directed toward something very different, namely, the presentation of nature at is most poetic, made abstract to some degree by an emphasis on passages of color. About three-quarters of the painting is devoted to a blue, gray, and green background, energized by the inclusion of brushy, abstract effects. The painting’s large piece of sky bottoms out on top of a green and greenish-yellow meadow, encouraging the view that we are in fact in front of a countryside scene. Running through the middle of the composition, and edging off to the right side at either end, is a thick brown line—nonobjective but also tree-like. Blue Web is a picture in turmoil. It reminds us of the abstraction we are familiar with in New York, but it is also true it is a scene from nature.

Blue Web is neither a conscious reference to abstract-expressionism nor an avant-garde experiment. Its imagery argues for a view of painting driven by its own concepts and rules. In the second show, in the two vitrines on the stairs in the lobby of the Institute of Fine Arts, curator Lisa Banner has included several paintings and drawings. These works inevitably echo the works at FreedmanArt, but they are more austere. The painting Kappus (2016) shows a leaning structure severely isolated against a white background; the rounded top of the form holds the sticks together, as if connecting them, like spokes on a wheel. Kappus is the young poet to whom Rilke sent advice in letters over a few years. Rather than investing the painting with a dark view, White establishes a hopeful connection, one that brings the younger poet into a supportive dialogue with the great writer.

White is an original painter, an artist of a different order. His work may be seen as a refusal to affiliate himself with one outlook or another. The paintings convey a mood that can be read in a number of ways. White’s education has been literary as well as visual, and this comes through in ways that go beyond painting. I feel that one aspect of his work is metaphysical, filled with poetic emotion. At the same time, he offers us an exceptional visual configuration that must be read as art—as entirely visual rather than literary. Given his independence as an artist, we can only admire the intelligence and technical skill with which he approaches painting. American art now is too often oriented toward the surface, toward entertainment. In contrast, White not only gives us something to see, he gives us something to think about.

Kit White: The Nature of This Place at FreedmanArt and the Institute of Fine Arts

Jonathan Goodman

Hi,I check your blog named “Kit White at FreedmanArt and the Institute of Fine Arts” daily.Your humoristic style is witty, keep up the good work! And you can look our website about proxy server list.

Beautiful, soulful art that somehow feels like fine classic literature.

Dont know how but the deceptively simple images embody palpable, vibrant stories. Magic.

Thank you