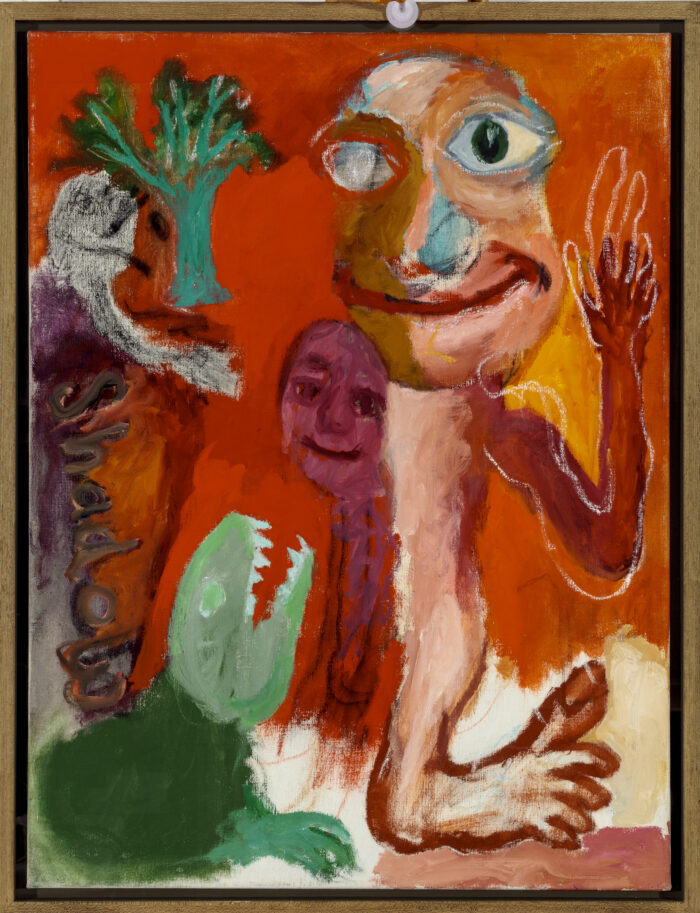

Glowing with phosphorescent color and figures that hybridize quotidian and fantastical realms, the work of Ken Kiff is too purposeful and too syncopated to qualify as exclusively hallucinatory or surreal. Rendered with a range of mixed media materials on surfaces varying from cardboard to stretched linen, Kiff’s work casts psychological insights into physical instead of mental terms, populating the cosmos of his painting with a system of images that form a personal iconography that vibrates with an otherworldly aliveness. Kiff, who died in 2001, spent his career teaching at Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art. A celebrated British artist who cultivated an intuitive but studied approach to color and form, Kiff improvised a mode of modernist painting that displayed sensitivity to color’s inner logic that the artist also found in the rhythms of music and poetry.

People of the Otherworld, on view at Albertz Benda through August 11, is a group show curated by Dr. Kathy Battista that places Ken Kiff in conversation with a constellation of contemporary artists across the United States. As Battista observes, Kiff’s imagery and thematic concerns appear in each of these living artist’s work: Kate Barbee, Hiba Schabaz, and Elif Uras explore the divine feminine; Coady Brown, Kim Dingle, Joshua Petker, and Jessica Westhafer probe an algebra of suffering induced by everyday living, and Sarah Bedford, Ken Gun Min, and Kathy Ruttenberg mine transcendentalism and the sublime in their figurations of nature as a site of beauty, terror and deliverance. These works are juxtaposed against a selection of key pieces by Kiff produced between 1965 and 1999. The effect is the articulation of a subtle history nestled within art history: a pattern of feeling and insight bracketed by the mid-twentieth century and the future-present which marks Ken Kiff as a conceptual lodestar. This “subtler history” is, perhaps, that of a sensibility that finds refuge in a disconcerting merging of inner and outer realities, and that deploys levity and fantasy as serious tools of protest against the tyranny of conventional experience.

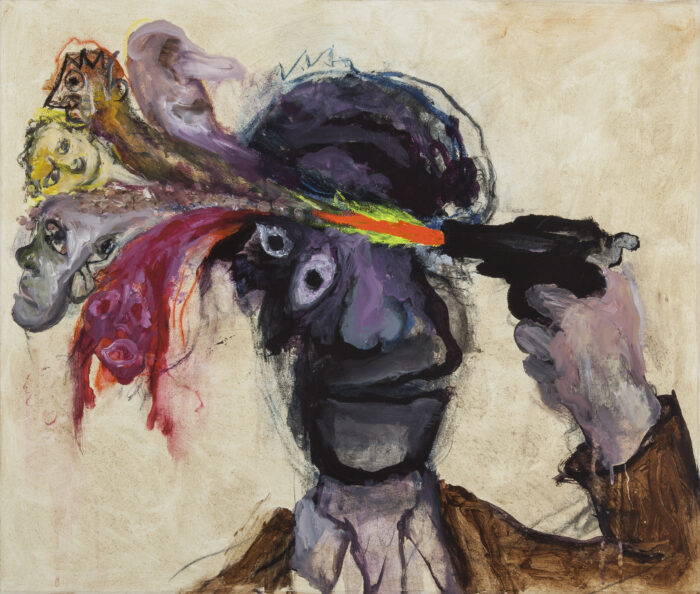

Ken Kiff’s paintings are funny. His figures appear in their own worlds, plodding across the composition in worlds that seem psychologically isolated yet compositionally linked, creating dissonance between how they relate to each other narratively and how they do so compositionally. In Yellow Woman in the Street (1975) for example, a bulbous purple head lopes across the foreground on a big blue foot, while the female subject, bathed in a saffron aureole, walks in the other direction. Between the two, a head hangs upside-down and cross-eyed. The obliviousness of each figure to the others is resolved in the harmony of their color palette, which reconciles opposite colors (yellow and purple) by way of their shared blue-green shadows. While these scenes could be read as whimsical and silly, works like The Poet: Mayakovsky speaks to the palpable unease that tremors within Kiff’s work. The Poet depicts the Soviet poet and Futurist group member Vladimir Mayakovsky in the midst of suicide, having shot himself in the head. The bullet wound–a smear of neon orange and green– has freed a chorus of characters from Mayakovsky’s brain: one gray and despondent, one grinning and mirthful, and another whose eyebrows are raised in either shock or fear.

Put another way, the works might be read as emanations from an ontological condition of ambivalence. There are too many characters– too many voices–vying for space in one’s interior world. Like the Latin from which it is derived (“ambi” (both) and “valence” (strength), ambivalence describes the state of harboring competing convictions or being pulled between disparate scripts. While Kiff’s work speaks to the isolation and pain symptomatic of this paralysis, it also identifies possibility nestled within ambivalence as a state of suspense and possibility. Kiff’s painting opens a third space–an “Otherworld“–that smuggles these disparate and incongruous voices–personified as characters– out of reality and into a domain where they can roam side by side. This fascination with ambiguity and multitudinousness is evidenced in the work of other artists in the show, too. Coady Brown’s luminous figurative works probe the precarity of our relationships and the vicissitudes of feeling, Ken Gun Min’s fictive landscapes pulse with natural supernaturalism, and Joshua Petker’s blue-toned specters float between materialization and dissolution. In particular, Kathy Ruttenberg’s bewitching “Spider Bite” (2023)–a life-sized sculpture of a woman holding a spider’s web–hovers between realism and a fable, presenting an enchanted world that holds magic, sensuality, and abjection in delicate proximity.

In some of Kiff’s works, multiple selves appear as bifurcated parts of a whole. In Shadow (early 1980s), a one-legged man with a big red toe and one bulbous eye raises his arm to a transparent gray figure. In Two People, a man and a woman regard each other from their respective islands, two halves of a cracked continent. Here, as elsewhere in Kiff’s work, the artist has jettisoned the conventions of scale. In both Shadow and Two People, the man’s head is massive. These experimentations with proportion cast psychological entrapment onto the formal plane. We are multiple, ”born” of too many origins; there is no self. Self is only a position of equilibrium, which bloats, shrivels, and contorts when it comes into contact with the world of other objects. The self that Kiff depicts–liquid, flimsy, balloonish–evaporates, curls, or inflates inside the scene. The humor of this condition isn’t lost on Kiff. In Shadow, the figure’s droopy eyes issue a benevolent gaze from his giant head. His red smile bends across his face like a Twizzler. As visual poems about the awkwardness of consciousness, Kiff’s work could be read as a meditation on subjecthood, and thus as cultural critique. At the same time, however, such an analysis would prove difficult. There is no satire in Kiff’s work; his point of reference is consistently hidden, and there are no clear allusions to the laws or customs that have instigated the distortions of his subjects in the first place.

There is much more to be said about each of the living artists included in People of the Otherworld. In one way or another, I think these problems of consciousness show up as subject matter within all of their respective formal compositions. What characterizes their practices as collectively “Kiffian” might be the urgency of their hunt for a new visual vocabulary to articulate the complexity of lived experience. When Kiff writes that he appreciates the “natural complexity of painting,” he identifies the capacity of painting to reconcile parts of reality that other mediums might not. While forces from without insist upon blunt binaries that force choices between this and that, Kiff and the living artists with whom his work converses mark incongruence as the precondition of a pattern.