Joani Tremblay: Intericonicity at Harper’s Gallery

January 26 – March 11, 2023

All images courtesy of Harper’s Gallery

Intericonicity, the title of Joani Tremblay’s solo exhibition at Harper’s Gallery, is a term developed by theorist Gérard Genette for the presence of an image within another image. In the paintings on view, Tremblay engages with “Intericonicity” both conceptually and formally, as she develops fictitious landscapes from digital composites of real and imagined scenes, and then paints frames on those scenes, creating the effect of an image within an image. What emerges are subtle meditations on the relationship between inner and outer topographies.

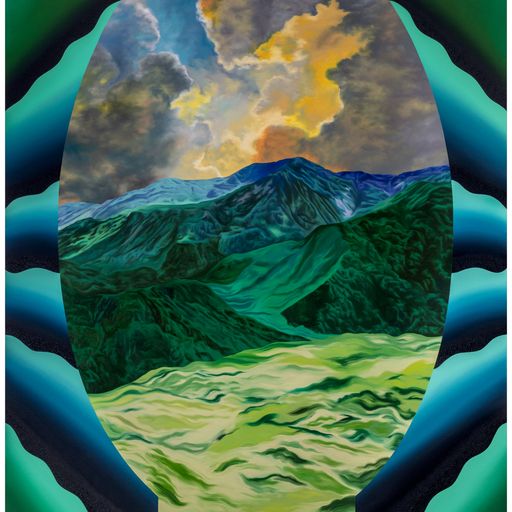

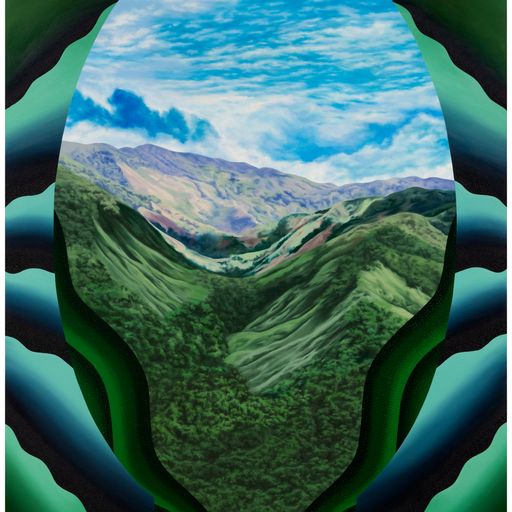

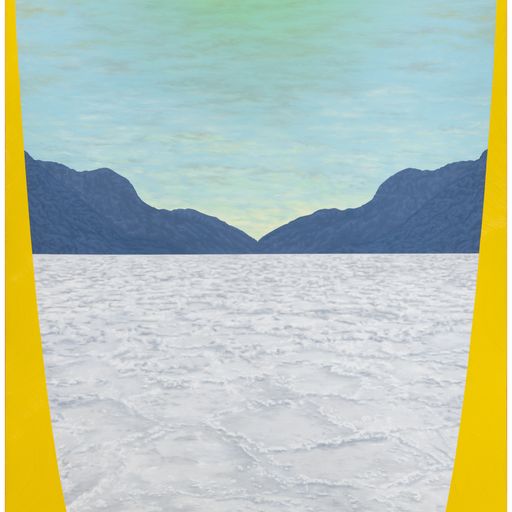

An amalgamation of virtual, physical, remembered, and imagined topographies, first rendered digitally and then transposed onto canvas, Tremblay’s framed landscapes are enigmatic in two ways. First, none of these paintings depict real scenes but are rather composites of actual and fictive ones. Second, the layering of light and dark colors in the work’s foreground creates the optical illusion that the shapes are swimming both toward and away. This phenomenon is evidenced in Untitled (farmland valley), where pale green light seems to pool in the painting’s foreground, making the front of the work more abstract than the sharply creased mountains in the background. This geographical uncertainty (where are we?) coupled with temporal ambiguity (are we arriving or are we leaving?) produces a kind of open secret; the frame acts as a grand but impenetrable gesture towards an imaginary landscape that glimmers on the edge of recognition. In Untitled (Laurel Highlands), 2022, for example, billowing clouds cut across with shadow and light recall the radiant cumulus rendered by Charles Curran. This realism is counterbalanced with surrealist elements; in Untitled (Mt. Davis), river water hugs the sharp edge of the framing canyon, as though it has been tattooed on the rock. Tremblay’s work is complicated in an uncomplicated way; her frank explorations of color and landscape are matched by a frank refusal to locate the viewer anywhere recognizable in time or space.

Tremblay has spoken about the role that Agnes Martin, Judy Chicago, Milton Avery, and Arthur Dove have played in her development as a painter. In her depiction of the natural world, her precision, and, most notably, her use of framing devices within the visual field, Tremblay’s work seems to hold particular resonance with that of Georgia O’Keefe, a comparison that could be complicated for a contemporary female artist given O’Keefe’s status as the paradigmatic “Modern Female Painter.” O’Keefe’s undulating forms were often read, by twentieth-century critics, as oblique renderings of the female body–a kind of visual “écriture feminine,” or “feminine writing”–a term coined, in the 1970s, by the literary critic Helen Cixous for work created by women that mirrors the multitudinous, curving forms of the female body. At this contemporary moment in both identity politics and art criticism, such an essentialist reading of gender–coupled with claims to its aesthetic implications–feels wincingly dated. O’Keefe and Tremblay are both female painters, but that’s not what their work has in common.

To this end, it’s worth thinking about Tremblay as a contemporary heir to O’Keefe simply because their work has certain visual similarities; luminous and crenelated mesas and canyons, saturated, hard-edged flora and fauna, and rolling clouds. Perhaps most significantly, Tremblay and O’Keefe make use of frames within their work. O’Keefe, who, as a child, enjoyed holding donuts up to the skyline to peer at the blue through the pastry’s hole, retained this affinity for apertures when she started painting:

…when I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes in the bones—what I saw through them—particularly the blue from holding them up in the sun against the sky as one is apt to do when one seems to have more sky than earth in one’s world . . . they were most beautiful against the Blue.

Going beyond O’Keefe’s “holes in..bones,” Tremblay uses frames to announce the parameters of the visible world while destabilizing our spatial and temporal relation to it. In this sense, the landscape glimpsed through these portals harbors an affirmative reticence; an invitation to (partially) glimpse a scene that is either cresting or waning from view. And yet, there is no sense that the work is withholding access to the narrative fruition of a sweeping panorama. In Untitled (Death Valley), for example, symmetrical yellow forms bookend scorched, white earth, which stretches out towards the horizon. While these built shapes narrow our field of vision, they complement rather than curtail the view, trading limitless vista for the aesthetic satisfaction (and consolation) of beholding oblivion, contained.

The conceptual difficulty of Tremblay’s work arises in this capacity to neither present nor hide the landscape. Her paintings assert aesthetic fulfillment in grace as formal simplicity: green hills, flat, towering succulents, and a peach-colored sky. In their ethereal luminosity, one could argue that the works enact spiritual fulfillment, too; this poetic exaltation of the landscape evokes the writings of the American Transcendentalists, who found God in both the human imagination and the natural world. The spiritual rigor that pulses through Tremblay’s work brings to mind a poem by Emily Dickinson which describes the transient architecture of human experience giving way to God’s unimpeachable Grandeur at its center: “All Circumstances are the Frame / In which his Face is Set.” In Tremblay’s paintings, the “Circumstances” of built environments “Frame” nature’s “Face” with precision, tenderness, and lyricism.