Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles is proud to present ‘Jack Whitten. Self Portrait With Satellites.’ This commemorative survey celebrates Jack Whitten’s (1939 – 2018) unique ability to convey the power of philosophical, scientific, and mathematical concepts through an exquisite abstraction. The first exhibition in LA devoted to the artist in nearly 30 years, the presentation opens in conjunction with ‘Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963 – 2017,’ currently on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art through July 2018 and traveling to the Met Breuer in New York.

‘Self Portrait With Satellites’ takes viewers on a journey through the various permutations of abstraction that span the artist’s entire career. The exhibition brings together self-portraits and other paintings from Whitten’s own personal collection, many of which the artist studied on a daily basis, and offers an intimate glimpse into the artist’s core beliefs about art, his deep philosophical concerns, and the people that inspired him.

As Whitten wrote in a studio note from 2012, ‘all of my memorial paintings are gifts to the people that inspired them… they are not mere dedications… they are gifts.’ On view will be works that pay homage to his creative influences – such figures as Allen Ginsberg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Wayne Thiebaud – and paintings honoring his family, including his mother, father, brother, daughter, and wife. The exhibition also includes the last work Whitten made before his death, ‘Quantum Wall, VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love In Painting)’ (2017).

Complementing the exhibition, Hauser & Wirth Publishers will debut its new book ‘Jack Whitten. Notes from the Woodshed,’ which collects Whitten’s studio writings and other texts from the artist’s six-decade career. Edited by Katy Siegel, this publication provides a window on Whitten’s relentless artistic experimentation in the studio, exploring the way his practice intertwined with his daily life. Alongside transcriptions of Whitten’s handwritten documents are selections reproduced in facsimile, redolent of the studio’s atmosphere and the way the artist’s creative impulses pervaded every part of his world.

Over the course of his career, Whitten ceaselessly worked through a range of styles and techniques, experimenting continuously to arrive at a nuanced language of painting that hovers between mechanical automation and spiritual expression. The common denominators across the many phases of his artistic practice – which he describes as ‘conceptual’ – are zealous technical exploration and a mastery of abstraction’s potential to map geographic, social, and psychological locations, often within the African American experience. ‘As an abstract painter, I work with things that I cannot see,’ Whitten has said. ‘Google has mapped the whole earth. We have maps of Mars. We don’t have a map of the soul, and that intrigues me.’

The exhibition begins with a group of paintings that honor Whitten’s family, with each work embodying specific attributes of its subject through the artist’s idiosyncratic approach to materiality. For ‘Mother’s Day 1979 for Mom’ (1979), Whitten used a hair comb to rake through and uncover a colorful geometric abstraction. Drawing parallels between his art-making and his mother’s preoccupations, Whitten spoke about the artistry with which she reworked second-hand clothing into new garments for him as a child: ‘When I use words like construct and deconstruct, reconstruct, I’m doing what my mom did. My mom was the first great recycler.’ ‘A Headstone for Mose’ (1992), a tribute to Whitten’s father, is evocative of an African totem, while ‘The Hairdresser: For Sister’ (1994) incorporates a mirror and hair to honor his sister, who was a hairdresser in Bessemer, Alabama. ‘Confirmation | Happy Birthday Mary’ (1979), celebrates the artist’s wife. Also on view are two works associated with his daughter Mirsini – ‘Petunia’ (1964) and ‘Little Data’ (1991). ‘E Stamp #1 for Billy (Little Bo Peep)’ (2007), is a loving gesture toward the artist’s late brother, a stylist to entertainment stars. Each of the works in this selection reveal the artist’s profound ability to give tangible form to the spirit of people close to him while also striking universal chords that resonate with the viewer through the language of abstraction.

Born in Bessemer, Alabama, in 1939, Whitten was brought up by his mother and came of age in the segregated South. ‘When you are raised with hate all around you, and then you got a family who teaches you love, you have people in the church who are teaching you love, you got a family network.’ In 1960, after years of being an active participant in the Civil Rights Movement, Whitten left the South and headed to New York to attend Cooper Union, where he would form another network. During his transformative time in New York, Whitten was mentored by Willem de Kooning and Norman Lewis, and came to know Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence. The assimilation and exposure to Abstract Expressionist methodologies spurred Whitten to experiment with the same figurative, self-reflective gestures to create works that were both autobiographical and political.

In 1968, Whitten began to shift from painting in an expressionist style to exploring the conceptual potential of his practice. The major transitional piece ‘Satori’ (1969) – its title comes from a Japanese Buddhist term for enlightenment — exhibits Whitten’s interest in geometries in the confluence of figurative brush strokes and a hard-edge shape. Whitten once described this painting as ‘a gift’ because it allowed him to enter a new phase: ‘That was the first big awakening I had. I felt I had crossed another threshold.’

As Whitten continued to push his practice forward, he entered the 1970s with an emphasis on the use of tools and a grid system to distance himself from the canvas. ‘Self Portrait’ (1979) is an abstract image of the artist with signature neckerchief and mustache, within a series of vertical and horizontal lines that break the picture plane. Paintings on view from 1979 to 1989 reveal Whitten in a period of intense experimentation and reflect his intellectual engagement with new developments in science and technology. In 1983, he began to work on circular canvases, as seen in ‘Self Portrait With Satellites’ (1984), which utilizes both oil and acrylic to illustrate the artist returning his focus to the gesture. This circular relief calls to mind systems of celestial navigation, while also alluding metaphorically to the artist’s personal orbit of close friends, family, and influences.

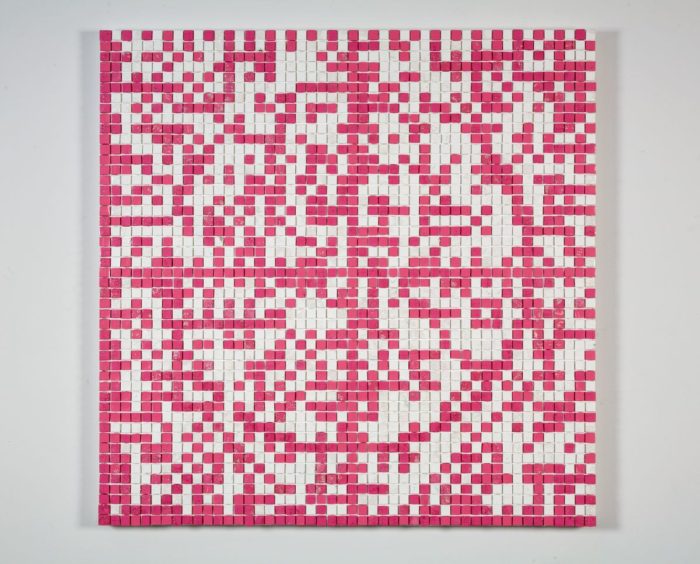

The exhibition concludes with a group of works that pay homage to the artist’s intellectual heroes – paintings that lived in the artist’s own private spaces. ‘The Ginsberg Mandala: For Allen Ginsberg’ (1997), a tribute to the Beat Generation poet, and ‘Bar Code, # II Lateral Shift’ (2008), a dedication to Robert Rauschenberg, hung on the walls in Whitten’s studio break room, where he could continue to study them over lunch each day.

This exhibition also includes the final work Whitten created before his death in January 2018. ‘Quantum Wall, VIII (For Arshile Gorky, My First Love In Painting)’ (2017), shimmering with brilliantly colored acrylic paint tiles, celebrates the beauty of the universe’s fundamental opposition to closure. ‘Quantum mechanics has rendered obsolete any notion of a wall,’ Whitten explained. ‘Quantum Walls is not to be misunderstood as a stand-in for utopia… I only want that which is possible.’

Writing via press release provided by Hauser & Wirth.

Photographs provided by Hauser & Wirth