Jamie Martinez: It was a pleasure meeting you at the opening of your solo show “I will Draw You a Fly” at Field Projects last month. Can you talk about your background in the arts and your journey to becoming an artist in New York?

Amanda Nedham: Hi Jamie, really nice meeting you as well, thanks for coming out. I grew up just outside of Toronto and moved there to do my undergrad in printmaking at OCAD U, spending my third year studying abroad in Florence. At that time I hadn’t drawn since I was a kid but taught myself as there was no printmaking equipment. It really changed all of my priorities and I have been working in representation and grey-scale ever since. Upon graduating I joined my first gallery and just drew for a few years. Eventually, the drawings were so labor intensive and I was getting burnt out so I applied for grad school at RISD and left there with an MFA in 2014. RISD pushed me away from drawing, something I had wanted, and it wasn’t until a stint in Abu Dhabi that I found my way back to drawing. And New York.

JM: Can you Elaborate on the “stint” that made you go back to drawing and New York?

Amanda Nedham: Two things happened. Firstly, my partner was working for a fairly progressive arts organization in Abu Dhabi and I decided to go along. This meant on top of my visa application for the States I was also applying for a visa in the UAE. Trump and Trudeau had just been elected and I started to think about my Canadian citizenship, my ability to move. This led to further meditations on borders and Canada’s legacy on the world stage. Canadian Prime Minister Lester B Pearson helped to establish the UN’s Peacekeeping force and I started to research the organization’s history. What resulted is a series of love letters from an imaginary peacekeeper boyfriend, tracing the history of missions. Eventually, these became drawings.

Secondly, I did some traveling and kept coming across examples of drawing in the world, operating as broadcasts, conversations on a continuum that were essentially fleeting by nature: the blood drawings in Steri Prison, pencil crayon drawings in abandon sheds on goat farms in the desert , Petroglyphs that have been in continuous use over thousands of years. This is the kind of drawing I am interested, or at least that impulse.

Why New York? We had lived here for a year after grad school and I was just really excited about the potential. And I have such a great community here. It is kind of that simple.

JM: In your recent solo show “I will draw you a Fly” at Field Projects, you showed a bunch of drawings mixed with a few sculptures. Anything from giraffe underwear drawing to a bent cigarette and ashtray sculpture. What was the inspiration behind this show and how does the work relate to Dian Fossey and Travis Walton?

Amanda Nedham: Well, it comes out of the project that began with the Peacekeeper. I continued to look at people who had traveled far away and had their value systems shifted. I first started reading about Dian after getting back to New York. I was interested in how her vocation entangled her within a complex colonial history. She was murdered – they still don’t know if it was at the hand of a research fellow or a poacher – and I wondered, having been dead three decades, if she could talk what would she say after all of this time? Would she be righteous? Apologetic? What could we learn from her radical conservation approach? At the same time that I was reading about her, I saw Travis Walton, alien ‘experiencer’ (whose account inspired the film ‘Fire in the Sky’), speak in Roswell, New Mexico during the 75 anniversary of the crash. Not only did he come off as genuine and traumatized, but he actually had spent almost 40 years re-examining his kidnapping, arriving at the idea that the procedures done on him were part of life-saving measures. He now believes that the aliens are benevolent, and that having seen so many planets born and die has informed their belief that every life form has deep intrinsic value – even some lumberjack who accidentally walks into a laser beam. He seemed like a good compliment to Fossey – an offering. Someone to use to coax her out so we can engage her. The exhibition is all offerings. More than two dozen drawings refract her biography and/or attempt to satiate desires. The sculptures operate in the same way, however, the chair is the surrogate body, the stand in. A place for her in this world.

JM: You are also participating in a two-person show called “I found the source of the problem and I cut it out” at 5-50 gallery with Tatiana Istomina. It seems like you both compliment each other’s work. Can you talk about the process of putting this show together with her?

Amanda Nedham: Sure, Tatiana and I met at a show I co-curated with Kyle Hittmeier at SPRING/BREAK Art Show, 2018. We had a really great conversation and kept in touch. After seeing one another a few times in passing she reached out to me about the potential of showing together. I knew she was making work around Hélène Rytman’s death at the hand of her husband, and coincidentally I was making work about Fossey. But she did not initially know this. We met up and there we were, both making work centered on two murdered women. We started talking about our mutual interest in historical wounds, memory, violence, hierarchies, drawing, and sculpture. The symmetry was actually quite profound, and we both ended up putting in the exhibition a severed hand, cigarettes, ghosts, thematic books, etc. Even the palette was complimentary. She has incredible material agility and laying out the exhibition was quite fluid in the way that so many works seemed to find poetic proximity. I have so much respect for her rigor, her humor, and it has been a really wonderful experience working with her and everyone at 5-50 Gallery.

JM: Jamie Martinez: Congrats on the two-person show you are in with Amanda Nedham who I already talked to. I am familiar with your work since I previously showed it at my gallery, The Border Project Space. Can you talk about your background in the arts and your journey to becoming an artist in NYC?

Tatiana Istomina: Thanks, Jamie. My background is far from artistic; I come from a family of scientists and have worked as a researcher in Moscow for a few years before coming to the US as a Ph.D. student in geophysics. I was studying at Yale University and took my first art class there, and this was the beginning of the journey you are talking about. I became very interested in contemporary art. After getting my doctorate degree I decided to take a break before starting a full-blown academic career in science. I came to New York, got into an art school and then stayed on. My life is not the kind of life I would have had if I remained a scientist; it’s very odd, insecure, and unpredictable, but it has its own perks.

JM: It does? What kind of perks?

TI: First of all, it’s the freedom of doing what you want, and in the way you want it. But this freedom is also a major challenge, because unlike science, there are few or no guidelines in art that you can follow, and you are essentially on your known.

JM: You are currently showing a series of soft sculptures that is part of the project Philosophy of the Encounter, loosely based on the story of Hélène Rytman, who was murdered by her husband, prominent philosopher Louis Althusser, in 1980. Can you tell us more about this project?

TI: I became interested in this story because we know so little about it besides the basic fact of the murder. Many of my works start with stories like this: poorly known, morally and psychologically ambiguous, perplexing. I make work to try to understand what happened, what didn’t happen but could potentially have happened, and what it meant for those involved, and what it means for us today. I think this is one of the functions of art: it can help us see and understand things that cannot be seen or understood in any other way. Because there’s no single interpretation of any of the stories that interest me, I often work across different mediums. In Philosophy of the Encounter, I use puppetry, film, sculpture, painting and text to create what could be an alternative history of Hélène Rytman’s life and death, narrated by herself. A book version of this project, titled Philosophy of the Encounter, has just been published by Pinsapo Press and is available for sale at their online bookstore.

JM: Do you have any other shows or events coming up?

TI: I will be showing Philosophy of The Encounter as a solo exhibition at Texas State Galleries in San Marcos this coming fall. After that, I’ll be starting an artist residency at Van Eyck Academie in the Netherlands.

JM: What are you currently working on in the studio?

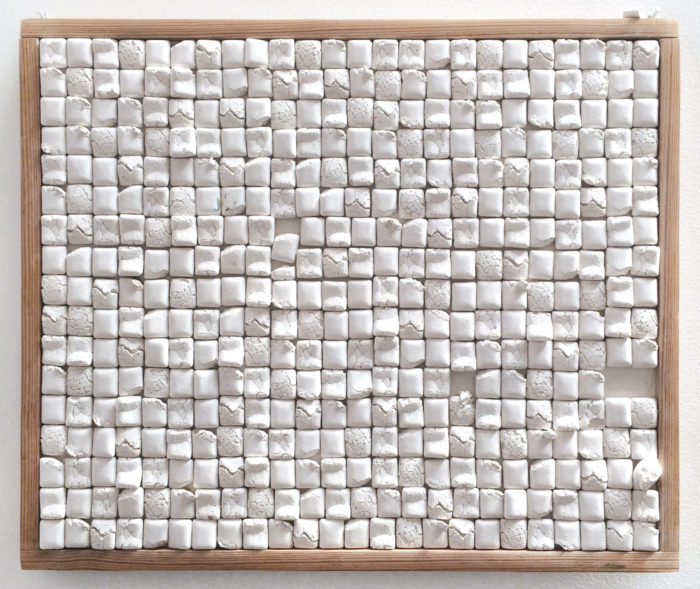

TI: These past few months I’ve been working on a group of works inspired by Euclid’s Elements: an ancient mathematical text introducing the fundamental axioms, propositions and proofs of geometry. Although it is now over 2,500 years old, The Elements is nearly perfect, breathtakingly beautiful system of abstract mathematical thought. My works recreate, reconstruct or respond to various segments of The Elements through drawing, painting and hybrid pieces made of fabric and ceramics. They transform precise mathematical arguments into uncontrollable and unpredictable painterly and material processes, and translate mathematical concepts into objects and images that are indistinct, tentative, and often flawed.

More recently, I’ve started a new set of figurative paintings; I am working on these and the mathematical works at the same time. The paintings are based on media photographs showing the body of Yuri Budanov, a Russian Army officer who was assassinated in Moscow in 2011. Budanov was a victim, but also a murderer, convicted to 10 years in prison for abducting, torturing and killing a young Chechen girl, and released early on parole. This case was extremely resonant in Russia, with public opinion polls showing widespread support for Budanov, despite his conviction. For some people, he was a monster, but for most, he was a war hero. The media images showing Budanov’s body have a strong personal significance for me. I remember hearing about his murder on Russian news and my first reaction was that of relief, even joy, as if some kind of great weight that was pressing on me for so long that I wasn’t even aware of it, suddenly disappeared. And then, of course, I felt shocked and shame, because it’s not right to be glad about another person’s death; but the relief was still there anyway. So this set of paintings is about ambivalence, the clash of emotions, the conflict of opinions, and the limit of what we know and what we can know about anything. Even though it may seem that this project has nothing to do with my works about geometry, in fact, both of them, as most of my other works are about truth and knowledge. What is truth? How do we know it when we see it? Is there more than one? What’s the difference between absolute, mathematical truth, and yours or my personal truth? Can we even ask such questions?