“Cloistered,” the small but dazzling exhibit of Ida Kohlmeyer paintings at Berry Campbell presents a lesson to all young artists struggling to break free of the influence of their mentors and teachers: The arc of an artist’s career is often a long one, and the influences that define you today will likely be different from the ones that mark your work in the future. Kohlmeyer’s work underwent a long series of stylistic transformations throughout her life. The exhibit at Berry Campbell (a reprise of a similar show from 2020) focuses on two pivotal years, 1968-1969. The five large paintings and one sculpture here represent a transitional moment in Kohlmeyer’s search for her own mature style.

Born in 1912 in New Orleans, Kohlmeyer began her painting career wholly under the sway of the Abstract Expressionists. She studied with Patrick Trevino as an undergraduate at Tulane’s Newcomb College. She was mentored after graduation by Clyfford Still. She befriended Mark Rothko (and rented her house to him) and worked with Hans Hofmann in Provincetown in the last years of his life. Kohlmeyer’s paintings from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s seem to cycle through all these influences. She produced Rothko-like panels of soft-edged color and Hofmann-like floating squares, often working on mural-sized canvases at the urging of Still. Kohlmeyer herself lamented the difficulty of breaking free of these powerful influences, influences she likened to a kind of religion. If it is always hard for young painters to find their original voices, it was especially so for a woman in mid-century America when Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg had canonized a handful of male artists with a singular notion of what constituted great art.

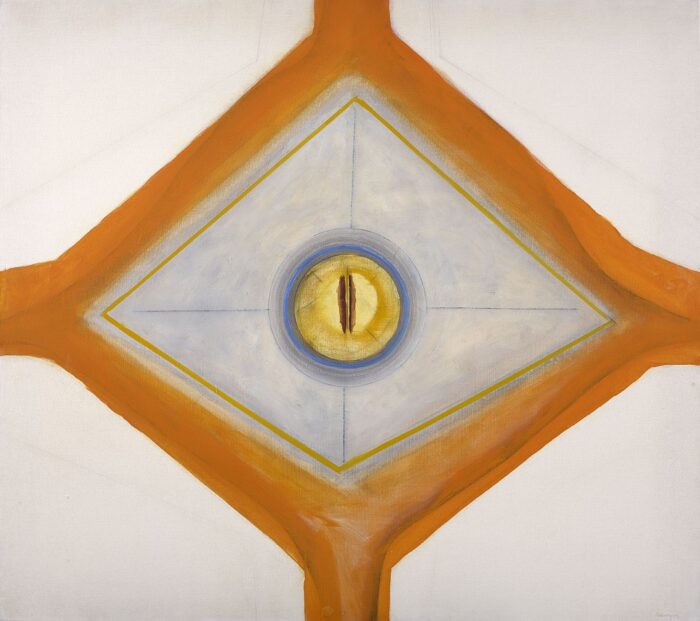

121.9 x 137.2 cm. © Estate of Ida Kohlmeyer. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell, New York.

The paintings on display at Berry Campbell represent Kohlmeyer’s first concerted effort to break free of abstract expressionism. All five paintings in this exhibit mobilize a very different vocabulary from her early work. Instead of her former blurry-edged squares and rectangles, Kohlmeyer focuses here on jewel-like faceted shapes, strategically centered and framed by empty space. In Orange Rhomboid (1968), a burnt orange diamond touches all four corners of the canvas, encasing an interior of soft grays with a sunny yellow core. Suspended (1968) again sets its interior forms–rendered in near-transparent washes of pink and violet– inside a green diamond case . Black Insert (1968) again plays with geometric shapes–a black diamond set above two intersecting rectangles–but the effect is softened by warm colors and the shallow, almost watercolored application of the paint. Cloistered #5 and Cloistered #10 play with the same kaleidoscopic forms using browns and pinks. Like the other three works mentioned, they are bilaterally symmetrical, with surfaces that vary in opacity.

Stacked #1, 1969, mixed media on canvas over wood, 31 x 9 x 9 in. | 78.7 x 22.9 x 22.9 cm. © Estate of Ida Kohlmeyer. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell, New York.

Kohlmeyer’s one sculpture here, entitled Stacked #1 (1969), engrafts small versions of these painted shapes onto the four sides of four cubes, stacked on top of each other like brief takes on a single theme. Clearly, for Kohlmeyer, 1968 and 1969 were years of aesthetic liberation. The works in this one room at Berry Campbell are moving without being sentimental, feminine without being decorative. They seem to be pointing to something new and very much her own. By the 1970’s however, Kohlmeyer had mostly abandoned this style, deepening her palette, and structuring her paintings around pictographic symbols and grids. Those later paintings also have their appeal, but for me, the paintings in the Cloistered series are her most original and beautiful.