“Immersion into Compounded Time and the Paintings of Firelei Báez” at the Mennello Museum of American Art in Orlando is at first pass an accessible and pleasant exhibition, neither a confounding academic treatise nor confrontational in terms of explicit sexual or graphically violent content. Additionally the artist herself is congenial and approachable, cheerfully answering questions and posing for photographs with new admirers and offering a plethora of talks and workshops at the museum in connection with the summer show. Further, as a longtime (now former) Miami resident, Báez is comfortable in the art crowd milieu of a tourism-driven city struggling to find aesthetic credibility against a backdrop of obscenely inflated real estate and a transient service-worker population.

Báez, 38, was born in Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic, which lies very close to the border with Haiti – a border that might truly be a wall – and going by her carefully worded artist’s statement, indeed her chief area of exploration is the Afro-Caribbean diaspora and issues of the lingering effects of postcolonial dislocation in American cities. The three monumental sized self-portraits on view, from an ongoing series called Can I Pass? also find Báez examining the obligatory path of racial identity and constructions of Western beauty ideals. Yet these paintings, such as Collector of shouts (April 21) and What is here is, as much as this there are characterized visually not by the adoption of reductive portraiture techniques but rather by symmetrical layouts, bright colours that typify ideas of the “tropical,” and vaguely mythical sensibilities that harken to a legendary, exotic past that does not exist. Thus an alternative reading would be a touch of sarcastic skewering of the expectations of mostly white museum-going viewers in the vein of Chris Ofili, albeit sans any unconventional mediums. I became further convinced that there is much more to Báez’s agenda than the inevitable “intersectionality” of the written descriptions of her work in a close examination of Study in blue (We have come to stir the other world, to cleanse ourselves, to connect our living to our dead here. A narrative of the history of New Orleans as an early American metropolis built largely through the labour of slaves and immigrants, the diagram incorporating a map and the figure of protester dressed in contemporary garb is partly covered by a billowing blue tarp – surely a reference to the city’s besiegement by Hurricane Katrina.

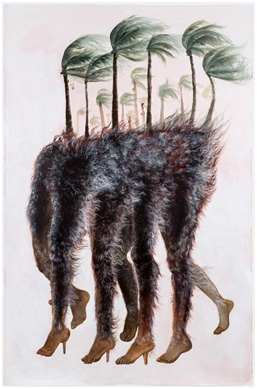

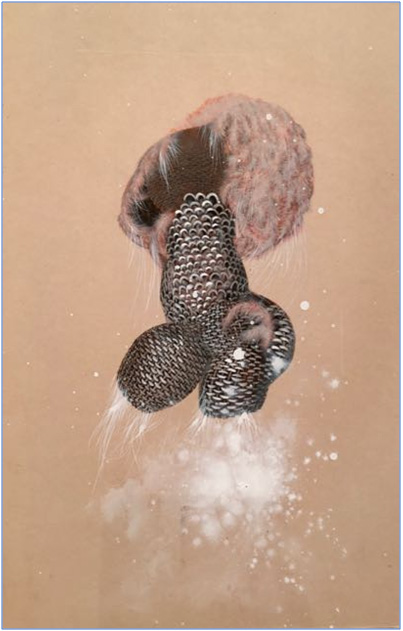

Less successful are a quartet of interpretations of Dominican folkloric Ciguapa, personifications of mountain demi-goddesses who bring both good and bad luck. Rendered in the style of a naturalist’s notebook sketches of island flora and fauna, these works read as curious experiments in Anthropocene transhumanism rather than powerful cousins to the Òrìṣà.

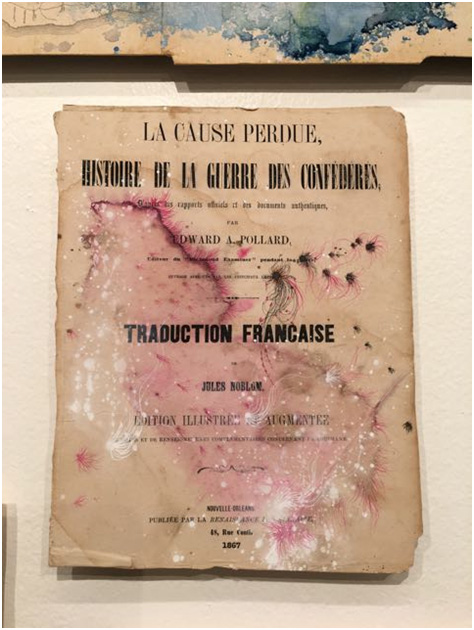

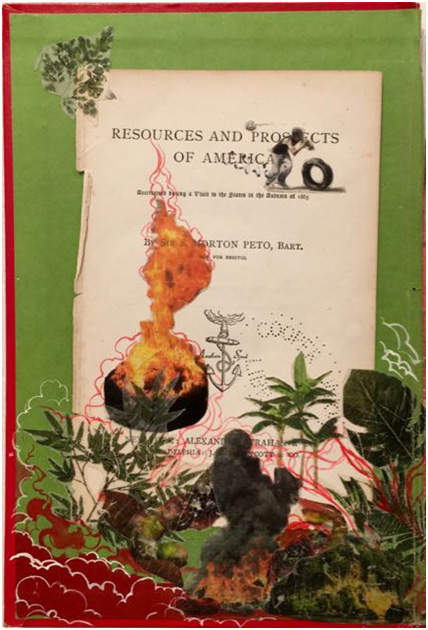

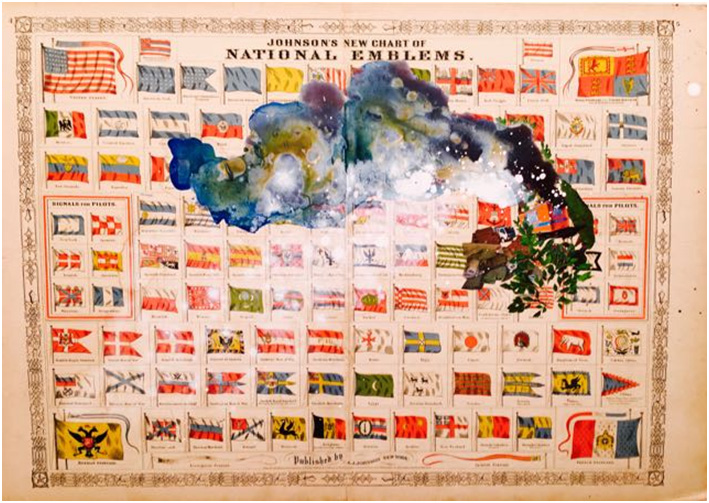

This is a tiny misstep especially viewed over and against the tour de force of the exhibition’s centerpiece, I write love poems, too (The right to non-imperative clarities). Typical of Báez’s oblique title cards, the word “archive” does not appear in the characterization of this intricate full-wall assemblage of original drawings, found objects, and modified or augmented books and documents. In fact I write love poems.. is a tribute to “archive fever” at full-on antiquarian levels.

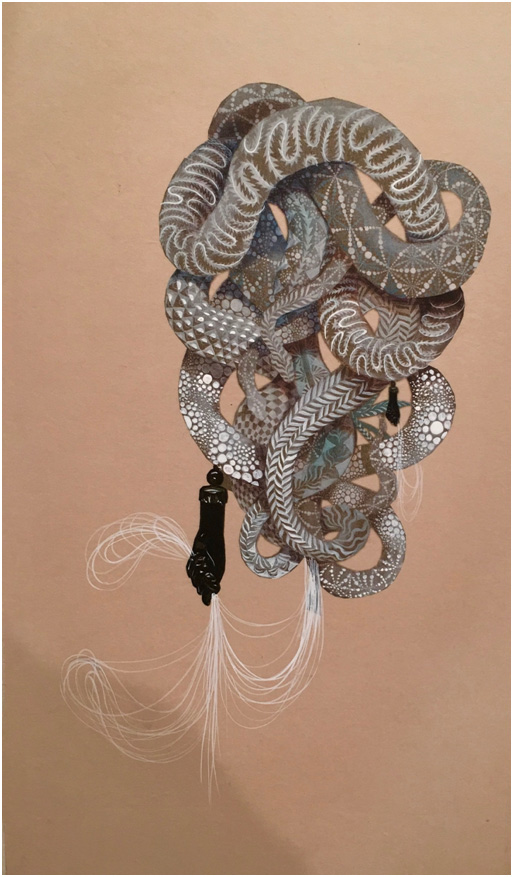

Over the pages of deaccessioned library books and discarded documents from mid-20th-Century Works Progress Administration projects Báez discovered in a second-hand bookstore in New Orleans, the artist has inscribed an extra-lingual dreamscape. Some images are legible enough – a roiling fire and acrid smoke billow from a topographic map of an oil field; a sugar processing factory schematic is stained with black and blue. More inscrutably, a talismanic ebony hand dangling from a tangle of jewel-encrusted serpents’ bodies clutches a handful of wispy white strands of fishing line filament, or hair.

Each individual document holds its own fascination, taken as a whole the mural-collage is cohesive and intriguing. Viewers seemed to realise they were examining something meaningful and needing of interpretation. I write love poems, too (The right to non-imperative clarities) is not the first conceptual work to tackle the historical complexities of Afro-Caribbean diaspora, but it is one of the most carefully executed and balanced between enigma and didacticism. Báez merits our appreciation and congratulations for undertaking this project that was hugely demanding and yet clearly a labour of love. Particularly in Florida at this moment in history, it fulfils a need, it reaches out to a new audience and it is a delight to behold.

The Mennello Museum of American Art’s “Immersion into Compounded Time and the Paintings of Firelei Báez” on view through 1 September 2019. Writing and photographs by Jean Marie Carey.

jean marie carey IS AN ART historian BASED IN miami, münster, and stavanger. she writes about modern and contemporary art for EXPRESSIONISMUS, the journal of visual art practice, lapsus lima, the empty mirror, kapsula, and the italian art society. CAREY is working on a 21st CENTURY biography of franz marc, AND is embarking on A PROJECT with the arkeologisk museum stavanger to connect MODERNIST UTOPIAS WITH PREHISTORIC ART, BLOGS AT GERMANMODERNISM.ORG and tweets @pollyleritae.