Daniel Gibson’s piece, titled You got to come from somewhere, you just don’t fall out of the sky depicts a man falling out of a sky that still partially envelops him, his hand firmly on the arid, pale-brown desert ground of New Mexico. This painting succinctly describes Gibson’s aesthetic and conceptual practice—it acts as a kind of mission statement for much of his work: an attachment to place, specifically the dry, yet not lifeless, region of the American Southwest, concurring with a focus on something that transcends location. The conjunction of spirit (sky) and material matter (ground).

As Gibson says, and is evident in the landscapes of his paintings, he is not a natural realist transparently depicting things as they are. His work transmutes the outer, objective world through the prism of memories, emotions, and senses that make up the inner phenomena of experience. The paintings remind us that we are never truly removed from the outside: our experience of the outside world contains our inner world. There is a subjective reality to place, to nature.

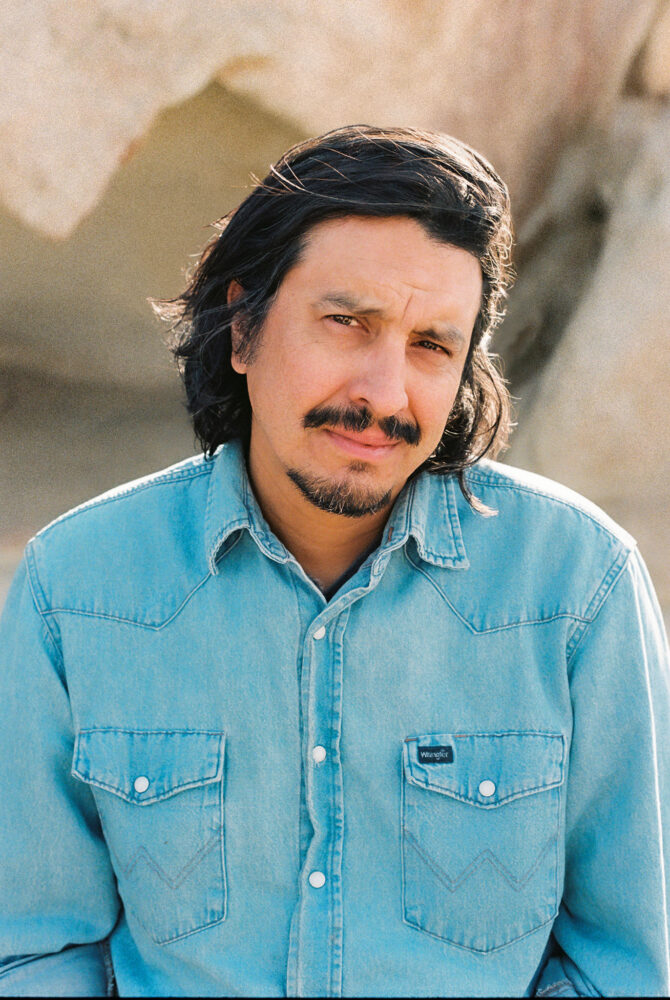

Gibson’s newest exhibition, Big Sky, currently on view at Almine Rech’s Tribeca gallery, is a subtle departure from his previous work: he moves farther from the human figure (or conceals the human within nature) while sustaining the devotion to the terrain of the Southwest and representations of inner life. To gain insight into Big Sky, I talked to Gibson about the place that inspired this collection, his use of color and flowers, and the stories he directly shares in his paintings and those he keeps for himself.

Teddy Duncan: The Southwest landscape is integral to this series and your previous work. What is your connection to the Southwest? Is that where you grew up? Do you still live there?

Daniel Gibson: I’ve been here [in LA] about 20 years, but I’m from the desert of Southern California, right outside of Mexicali. I grew up on the border. Since I’ve started working, I’ve been painting the desert. If you want to describe the paintings quickly, you can do it in one shot: it’s just a horizon, dirt, some cactuses or Ocotillo plants, and a sky. The paintings that are in the show, Big Sky, come from my time spent in the New Mexico desert. I keep going back to New Mexico and I’ve fallen in love with it. While I was there, I kept thinking about the connection between the sky and the Earth. Standing out there is different. You feel the sky closing in on you while you’re high up in the mountains, you’re sometimes at 9000 feet without knowing it. In New Mexico, you feel like you’re in the clouds and the clouds are grazing over you constantly. I’ve always felt a connection to the desert – I’m always drawn to places like that. I’ve lived in the city for 20 years, and I don’t paint the city. There’s some reason why I just always want to paint nature—to paint what I see and feel when I’m in it.

Teddy: Generally, in the contemporary art world, there doesn’t seem to be the attachment to place that there may have been in earlier regionalist painters—not many artists are focused on a particular place. What about the environmental formation or culture of the Southwest attracts you to it as an artistic subject?

Daniel: A lot of my work focused more specifically on the region I grew up in and with this show I expanded my view to another piece of the Southwestern landscape that still feels like home in a way, even though it is fairly new to me. I have a connection to New Mexico that I’m trying to understand better with this show – for some reason, it keeps calling me back and I wanted to look closer at that. My connection to where I grew up is historical and foundational and this focus on New Mexico is helping me to connect to something spiritual.

Teddy: What initially struck me about your Big Sky series was the vivid preternatural colors that flood the paintings, particularly the flowers. After reviewing your previous series, I see that this is a principle of your aesthetic approach. Why are those colors such a crucial compositional element of your paintings?

Daniel: I just love the brightness and colors of nature. I always try to avoid this answer, but my work used to be very dark. I was in a dark place in my life years ago. Now I’ve been free of drugs and alcohol for 10 years. But before that, my art looked very dark. I was just showing how I felt inside and how I felt about the world. When I started coming alive and having a second chance at living, the colors just naturally came. I want to show the brighter side of living life and being on this planet rather than showing a dark place. So, I choose color. And I choose it even when I do make work that touches on heavy topics. For example, when I paint colorful flowers, while they are beautiful and bright, a lot of times they will also represent a message about the cycle of life and death.

Teddy: When you say life and death are represented by the flower, is that because it has mortality?

Daniel: Yeah, eventually when winter comes, flowers die and maybe come back in spring. I’ve used flowers to represent people and also, life in general. I’m just kind of always painting stories about life and death and how we’re not just living on this planet; we are a part of this planet. We are like little flowers walking around with $50 shoes on. We’re just not tethered to the ground. And that the cycle of birth, growth, and mortality are a circular thing that just keeps going and going.

Teddy: Other interviews and press have characterized your work as a form of visual narrative and you as a storyteller. What is the story that you’d want the viewer to see with this newest exhibit?

Daniel: I have to start by saying that my paintings always have three parts to the storytelling- I feel like I’m often taking people through a few different phases when they look at them and take them in. First, you walk into the gallery, and you see flowers and landscapes. And as someone walks closer and leans in, they might start to notice the little details and making up their own stories. They might see a profile of a head that looks like a rock that’s covered up by grass or a face in the clouds. And as they are starting to notice these things, the next part of the journey is that the viewer starts digging deeper and realizing there’s also another story that I’m trying to show you, but I’m not forcing it down your throat. I’ll hide a the shape of a skull in a rock formation to call back to the theme of mortality. I’ll put a strip of a red line through a painting and, to me, it’s the border. But to you, at first it looks like a stem or a leaf or something. I’m kind of hiding my stories around for people to find right away or find years down the road.

Then there’s the other part, the part three of the story. That’s the story I don’t really tell. The story that I keep for me because this is also helping me move through life. The hidden story is about loss—about losing friends. And this is one of the stories I am telling (but also not telling) in this newest show.

I lost one of my best friends to substance use and schizophrenia. The last time he came to my studio, we traded drawings, and he was completely schizophrenic because of drugs and alcohol, and I didn’t really know how to hang out with him. So, we just sat outside in the parking lot of my studio. It was a full moon, and all these super big clouds were illuminating the sky – we sat and pointed out the clouds, turned them into animals, like you do when you’re a kid. I grew up with this guy. We both got in trouble together as kids. And I got sober and get to paint all day and do interviews with you and have this life. I have such a different life now. But I have a lot of friends that didn’t make it, like my friend Bill. I love him so much because he showed me the way of music and art and then, on that night, there we were just staring at clouds because we didn’t know what to say anymore. After a couple hours he went back out into the night, and I don’t really see or hear from him until I hear the tragic news that he passed away. And I was in New Mexico when I got the news. For the whole trip to the airport, I was just staring out the window at the clouds, remembering me sitting in the parking lot with him. Just staring at these massive clouds moving over the beautiful landscape and sending up my prayers. Sometimes I feel like I go back to New Mexico because I’m almost chasing those clouds now – looking for Bill. That’s the story that’s loosely written down in the info about the show, but I don’t really talk about it explicitly. So while I so often talk about life and death in the general sense of the greater human experience, I’m also always calling back to my own stories of my personal, lived experience too.

Teddy: There is a mixture of exactitude and play with reality—something that seems to be like a subjective reality of place—within your work. What I mean is that it seems like these are semi-realist depictions of actual places with your own twist. Do you go to a location to paint or are these from memory? Where do those memories arise from?

Daniel: I’m definitely not a landscape plein-air painter who goes out and takes a picture and tries to replicate it. Like for me, the images aren’t coming like how someone might paint a still life – where they look at a vase and flowers and paint exactly what they’re seeing. Not that there is anything bad about that way of making images, it’s just for me I’m trying to figure out how do you paint a flower in a vase with all the life you’ve lived and all the pain and all the happiness and memories and everything… and put all that into that flower? It’s hard to explain without sounding like a fucking hippie. How do you bottle up what’s inside of you and put it into a painting of a flower?

There’s one painting in the show, it’s just clouds moving through a blue sky, and everything is blue. That calls back to a specific memory from New Mexico where we stopped the car and sat on top of a hill because there was an amazing view of a storm rolling in. We just sat and watched that one evening after dinner, there was thunder and lighting, and a sunset peeking through – and I painted that, but it doesn’t look like what I really saw. I bring in elements from my imagination and try to bring in my own experience. In the painting, I’m trying to show what I felt, not what I saw.