By any measure—artistic, historical, symbolic—the Statue of Liberty is a triumph. Conceived by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and realized with the engineering genius of Gustave Eiffel, the 305-foot neoclassical figure standing sentinel in New York Harbor is more than an icon. It is a paradox in oxidized copper: imperial yet democratic, European yet American, fixed in form yet ever-shifting in meaning. Like all great public art, Lady Liberty is as much a mirror as a monument, refracting the ideals and inconsistencies of the culture that birthed her.

Bartholdi, trained as a painter and sculptor in the French academic tradition, was no stranger to scale or spectacle. He imagined the statue not simply as an artwork but as a gesture of ideological kinship—France offering a beacon of republican values to the United States a century after its revolution. That such a massive and idealized female figure should arise from the 19th-century male gaze is, in hindsight, as expected as it is loaded. The statue’s face was reputedly modeled after Bartholdi’s own mother, adding a strange matriarchal gravity to the colossal form, a kind of personal mythology folded into a national one.

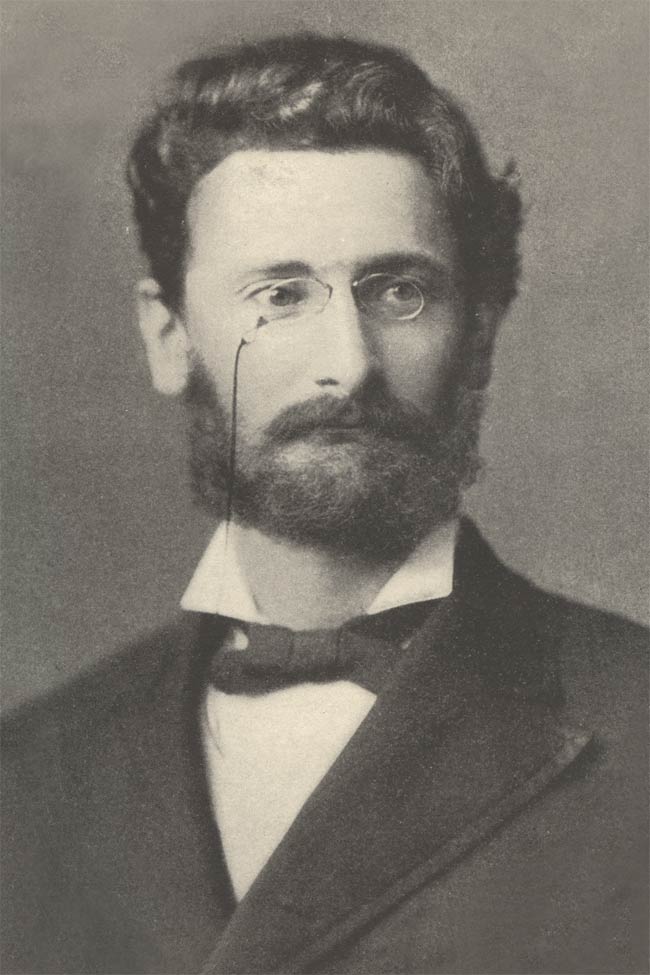

What’s often overlooked in popular retellings is how deeply democratic the financing of this monument was. In France, funds were raised through lotteries, public fees, and theatrical benefits. In the United States, where the statue’s pedestal needed its own financing, a full-blown crowdfunding effort unfolded. Joseph Pulitzer—yes, that Pulitzer—used his newspaper, The New York World, to galvanize small-dollar donations from working-class Americans. Contributions poured in from schoolchildren, shopkeepers, and immigrants, some as little as a penny, anchoring the statue in the communal rather than the elite. It is one of the earliest examples of public art made possible by public funding, predating today’s Kickstarter ethos by more than a century.

Yet for all its democratic trappings, the statue’s reception was never monolithic. African Americans, Native peoples, and suffragists immediately recognized the contradiction between the statue’s promise and their lived realities. Black newspapers of the era published scathing critiques of what they saw as hollow symbolism. And yet the statue endured—its meaning, like the nation itself, continually contested and reinterpreted. In 1903, when Emma Lazarus’s sonnet “The New Colossus” was affixed to the pedestal, it began its slow transformation into a symbol of welcome rather than mere independence—an immigrant mother as much as a nationalist muse.