Andrew Lyght is an inventive, challenging artist who lives and works upstate in Kingston. His art usually straddles the fence between painting and sculpture–all of the works in this fine show are placed on the wall, but many of them extend several inches toward to the open space taken up by Lyght’s audience. Closer in most ways to drawings than paintings, the works consist of thin, white, geometric designs drawn with a pencil on a single-color ground, with considerable physical support–dowels and thin strips of wood frame the image, which is held securely by the physical apparatus surrounding it. The individual pieces are highly interesting for their mediation between finely developed sculpture and subtle two-dimensional work, but in the end, it is likely best to describe Lyght’s efforts here as drawings/paintings held in place by sculptural supports. These days good art often occupies a place between genres, an expressiveness brought about in a hybrid fashion, and Lyght does this very well. He is adept in all the skills needed to put together these artworks, which not only remind us of their technical skill but also keep alive a distinctly modernist sensibility.

The bigger question does not lie in our appreciation of Lyght’s art, which has been exquisitely, but in our ongoing appreciation of and reliance on modernism as a movement. By now, modernist aesthetics, beginning with collage, can be seen primarily, and even close to completely, as historical–Kurt Schwitter’s great Merz collages began appearing in 1918, while T.S. Eliot’s verbal collage poem, The Wasteland, appeared shortly thereafter, in 1922. So both examples received public scrutiny more or less a century ago.

But, even though modernism’s history is long and established, it has managed to remain alive in our culture. Its achievements are sufficiently large, intellectually and formally expansive to permit the current usage of its style and methodologies. Indeed, Lyght’s art, while an homage in part, more truly functions as an extension of the modernist imagination. He is broadening both a way of thinking and a manner of making. There may come a time, relatively soon in arrival, when such an homage will lose its importance in contemporary art; already, much art is being made for online Internet experience, a medium that cannot be separated from the technology that enables it to be shown. In contrast, Lyght is very much low tech, an artist who can accurately also be called an artisan. The term “artisan” is not so much an old-fashioned referral as it is an enduring term for an honorable vocation. But much contemporary art has little patience for the slow, grounded emphasis on craft, which relies on the skill of the hand. Instead, many young artists prefer the speed achieved in present-day technology.

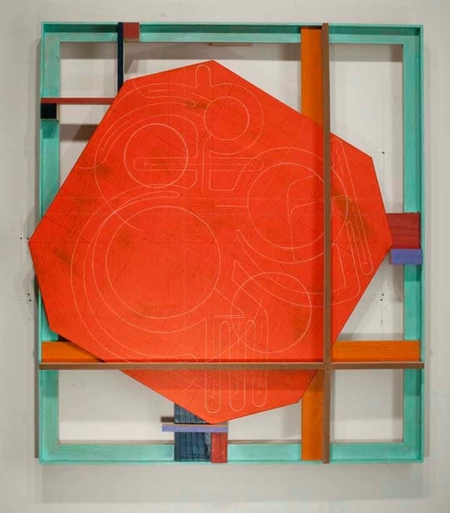

Painting Structures 645C (2017-18) demonstrates just how accomplished a craftsman Lyght is. The work consists of a red hexagon with sides of differing lengths, on which a design achieved with a thin white line is found. The line describes what seems to look like a simple labyrinth, dominated by several large open circles. The painting is held–imprisoned might be more accurate–by a series of thinnish wooden batons, one of which has been placed in front of the painting. The combination of elegant painterly values and a simplified, rough support creates a convincing double language. Another work is even more exploratory of the plane as a support for visual design. Called 564C (2-17), this work offers a black sheet, with the geometric imagery typical of Lyght drawn over it. Nearly falling out of the frame containing it, the painting is secured by cordage connecting the painting’s roof-like top and the bottom of the construction. The position of the painting adds to our sense of this work as something slightly, dangerously, off-kilter. It is an intelligent deconstruction of a painting.

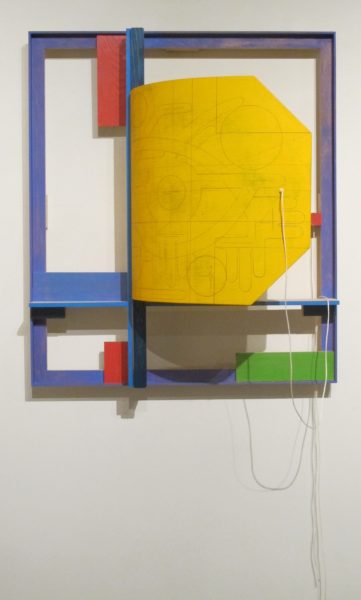

For this viewer, one of the nicest pieces was 456D (2018), an homage to Lyght’s activities with kites as a child in Guyana. This piece is composed of a curved yellow wooden sheet, again with a pattern that feels like it has been incised into the ground, this time by a darker pencil. An open blue frame surrounds the yellow plane that curves backward, toward the wall; the frame extends beyond the left side of the yellow painting, decorated by two small rectangles painted a muted red. A thin length of string attaches the kite to its support. Likely the most experimental and intricate work in Lyght’s good show, this piece may be strengthened by his memory of a childhood activity. If the metaphor at work here is truly that of flight, the artist has done a very good job of connecting a childhood game with art–an adult game. Lyght’s show doesn’t fully solve the problem of the weight modernism brings to bear on his work, nor does it determine the changes the future will bring to image-making. What Lyght does do is to re-work the tenets of modernism in a manner that is highly indicative of modernist conventions. He does this remarkably well. Indeed, Lyght’s skillful handling of his materials is a genuine advance in the art we see. The visual ideas he uses may have been established decades ago, but it is also true that here the artist uses what he has been given with imagination and aplomb. This show asks that we remain aware of the great legacy of the early and middle 20th century; and that we recognize the extent of the freedom modernism makes available to us in his art. Lyght is able to suggest such questions because he is as good as he is as an artist.

Andrew Lyght: Painting Structures at Skoto Gallery

April 19 – June 16, 2018

Jonathan Goodman