“She cannot be substituted for another,” a distinct voice declares in Disposable Utensils (2022), a polyvocal performance and interactive installation by artist Tianyi Sun (b. 1996). This statement, neither wholly ironic nor entirely sincere, emerges from an intentionally scrambled, whispered, layered, and fragmented tapestry of live and recorded speech. Amidst the stark and detached ambiance of the installation—featuring scattered recording equipment, a monitor displaying a minimalist dessert mukbang, white and purple LED lights, and etched transparent panes of plastic—this voice offers a welcome breath of emotion.

Who is this elusive “she”? Is “she” the faceless woman in the mukbang video, or perhaps the narrating voice referring to herself in the third person? Can we trust her words when her identity remains obscure?

Decades ago, the world entered what Jean Baudrillard termed “the era of simulation” in his 1981 book, Simulacra and Simulation. According to Baudrillard, society was saturated with media to the extent that symbolic representations, be it of people, places, objects, or events, could no longer be distinguished from their supposed “originals.” In this view, all facets of reality had been replaced by signs, and everything effectively had been substituted. Accordingly, Sun’s explorations of artificial intelligence, machine learning, time, and data center on what she calls “the reconstruction of embodied experience and its inevitable failure.” Her approach inherits Baudrillard’s theories and offers a compelling, updated perspective for addressing contemporary issues involving technology and society.

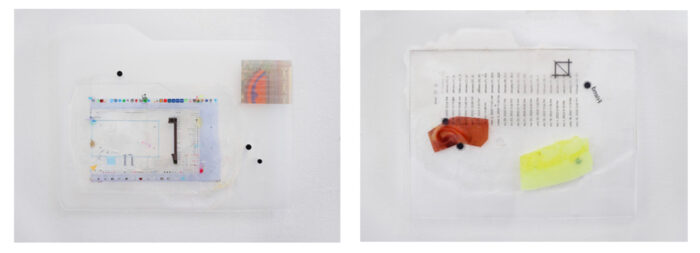

“She cannot be substituted for another,” the voice insists. The simulacra in Sun’s works possess unmistakable autonomy and complexity. In Disposable Utensils, mukbang replicates the conviviality of shared company, while ASMR-style whispers emulate physical presence. In Mid-Autumn_Adaptor (2023), silicone mooncakes and molded extension cord holders stand in as replacements for “authentic” sustenance, culture, and technology. Etched on the surface of The Shark is Curious (2023), an acrylic and aluminum bench that Sun has utilized in performances with her collaborator Fiel Guhit (b. 1986), we find a narrative about great white sharks. This narrative was generated by an AI that Sun and Guhit trained to craft stories, poems, and advertisements inspired by the objects it “observed” in its environment.

In Sun’s latest series, Softbox (2022), text is transferred onto transparent, wall-mounted panels the size of computer monitors, introducing a layer of discourse into the visual realm of computer icons and windows. In Softbox[Friend] (2022), a 12 x 14 inch pane of cast acrylic bears the word “Friend.” The text is printed in reverse, seemingly not for the viewer standing outside the screen to read but for a sentient presence within the screen to comprehend.

It is as though a conscious entity has typed this word from within the interface, to signal its identity and intent. This portrayal of screens and the suggestion of beyond-human intelligence evokes a sense of hope, in contrast to the now-clichéd fears of replacement propagated in much of the media. Sun’s simulacra do not just imitate; they engage in dialogue, demonstrating cognition, self-awareness, and agency, qualities that were once deemed uniquely human. In her work, our entanglement with screens is not a precarious dependency but rather an exquisite and uncharted friendship.

While a pessimist might bemoan our current era of instability and disintegration, artists like Sun enable us to reconcile with the present and perhaps even embrace failure as an integral aspect of our technological self-reckoning. Our navigation of digital space through sleek screens and high-speed networks has conditioned us to anticipate a certain “smoothness” in our daily interactions, Sun notes. Her work, on the other hand, delves deeper into the realm of imperfections, leaks, deterioration, and human errors. Sun articulates the allure of these aspects, stating, “Stumbling is something I’m interested in. Through stumbling, we come to look at things with a critical distance.” When AI stumbles, we catch glimpses of our past and future selves.

Ultimately, Sun says, “AI reflects us back to us.” Her work embodies the very essence of the post-pandemic world, where distance, hygiene, and preservation have given rise to a yearning for intimacy, permeability, and vulnerability. Nowadays, we go online to vicariously experience taste and touch, and we train AI to observe the world, tell stories, and write poems from a fixed position, like a body in space. Our desire to simulate embodied experience has led us full circle, face to face with ourselves.