Piero Manzoni was born in 1933. He grew up in Milan and began his artistic career in 1956. In terms of work and life, the figure most comparable to him is the French conceptual artist, Yves Klein. Manzoni is well known for his “Achromes”—canvases that are primarily white, composed of unusual materials, ranging from cotton wool to synthetic fiber to bread and kaolin. He’s also famous for packaging some ninety cans of his own excrement in 1961–an extremely ironic, deliberately downward estimation of his or anyone’s artistic value. Yet, over time, the worth of the cans has astronomically risen commercially. Manzoni lived only until 1963, so his career had the arc of a shooting star. But his slightly comic, highly intelligent, conceptual art not only posits new ways of valuing creativity. His works—the Achromes especially—are in many ways a forerunner of minimal art, as well as notional creativity that depends strongly on the idea it sustains and illustrates. In fact, the many Achromes available in this museum-quality exhibition demonstrate Manzoni’s mastery of texture and surface. He had a tacit recognition of contemporary art’s capacity, even at so late a time, for imagery that is beautiful.

Manzoni is also well known for his linea (line) drawings. In the gallery, there is a small room devoted to showing one of Manzoni’s works, a zinc cylinder covered with lead sheets that contains a 7200-meter line on paper. Made in 1960, Linea Lunga 7200 Metri (Long Line 7200 Meters) is a self-contained device, denoting Manzoni’s interest in content that is conceptually evocative without being visible to the viewer. So one has to imagine the line without seeing it—a requirement that surely is meant to stretch the audience’s inventiveness. The zinc container is interesting enough visually in its own right, but it is to be known primarily for its function as a container holding the image, which cannot be known by sight in usual circumstances. Because we cannot visualize the long line in actuality, it becomes clear that it is the idea of the line that counts. Thus, Manzoni is shifting the artwork from its existence as a physical object—although of course, in this case, the piece does, in fact, exist—to something ephemeral, something notional. Ideas by themselves are hardly visible, but they do enact a recognition that can be brought into a physical presence from the imagination, readable by means of the eye. The connection between the concept and its actuality is tenuous, so that it requires an amount of intellectual empathy leading to a visualization of the image as it would exist (and usually does) in the real world. While we cannot be sure that the line does exist in the container, we can believe it does. With the help of pictures of Manzoni working on the piece before the line was placed in the container, we know it does. This is an extreme act of imagistic intelligence.

The Achromes, which dominate the show, are wonderfully preemptive of future work—in particular, minimalism. Their color is almost always white; although, as I have indicated above, the materials vary. This, of course, influences the texture of the surface, which can vary from smooth to rough to silky (in the case of the latter, the fiber pieces). The works’ extreme structural simplicity leads to a formal cul-de-sac that can only be escaped by the use of unusual materials. In the case of the synthetic fiber Achrome made in 1961, the fiber looks a lot like torn cotton stuck together in clumps; the surface is rough and dense, giving the impression of unkempt hair or a wild, thick rug. Today we are used to this kind of work, but in Italy during the very early ‘60s, the work must have been seen as radical, prescient to a remarkable degree. Another work, from around 1960, consists of a series of cotton wool squares set next to each other; it can easily be seen as contemporary, even now, some seventy years after Manzoni made this artwork.

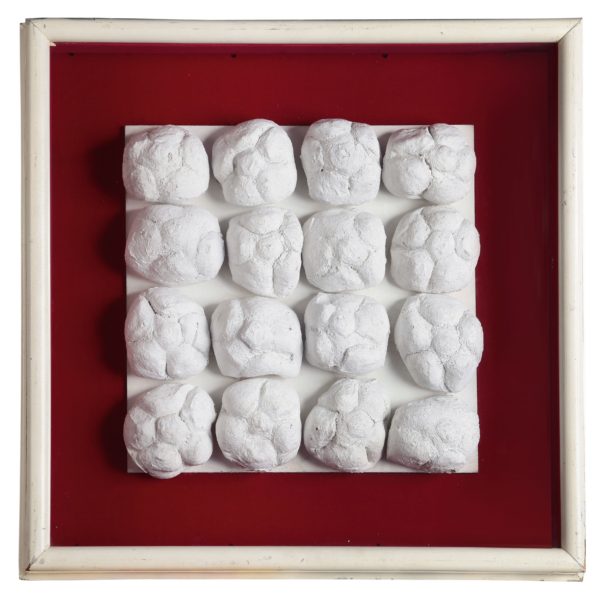

Another Achrome, made in circa 1962, consists of four rows of bread rolls covered with a slip of kaolin. The rolls, displayed with their tops visible, show the marks and slight indentations that characterize their raised surface. Here, given that the basic material is organic, the rows of rolls don’t seem to follow strict geometric rules in any fashion, although the white clay slip disguises their status as food and accentuates the objectness of them as individual items. Another Achrome, made around the same time, is composed with cobalt chloride, giving the surface the unusual hue of a mixed pink and white. Its unusual but elegant combination of colors makes the piece attractive, while the allover composition signals that there is neither a start nor end to the composition. The piece was made after the high moment of abstract expressionism, suggesting that Manzoni perhaps was looking at the American nonobjective art of the time. But this is speculation; what is clear is that Manzoni was pretty much alone at the time he was making these outstanding works of minimal abstraction. His isolation was that of someone ahead of his time.

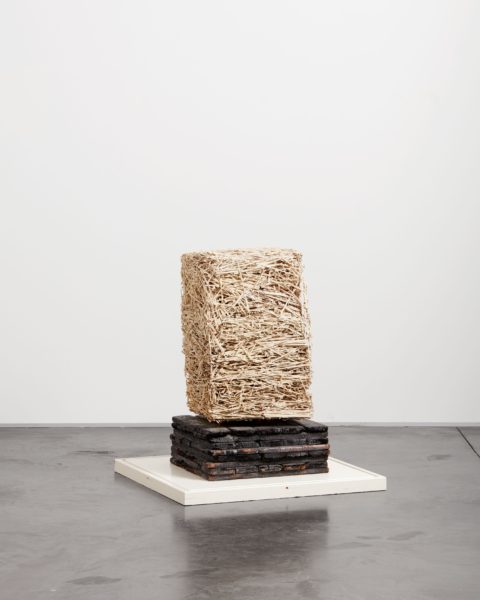

One Achrome, made in 1961, is one of the very few free-standing sculptures in the show. A rectangular mass, made from coarse straw treated with reflective powder and kaolin, rises from a burnt base set on the floor. It is a marvelous exploration of texture—the thick straw, colored an off-white by the kaolin, contrasts in a beautiful manner with the dark brown wood that supports it. While Manzoni did not belong to the Arte Povera movement, his choice of materials was poor in the extreme. Throughout the show, he made the most of the least, orienting toward a view of art that would be thought of as far-reaching in ways that may not have been understood at the time. Manzoni’s conceptual intelligence was extraordinary, but not necessarily given only to the abstract. One of the major, wonderful things we learn from this exhibition is his willingness to assume a certain idiosyncrasy in order to push ahead of the art of his time.

Piero Manzoni: Lines, Materials of His Time

At Hauser & Wirth (22nd st).

April 25 – July 26, 2019