Walking down the broad, half shaded sidewalk of East 43rd my feet have led me to the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice. The Midtown East location is off the art-goers beaten path but the lure of the current exhibition, Perilous Bodies curated by Jaishri Abichandani and Natasha Becker, is a convincing draw. The gallery space, situated on the second floor, is the newest addition to the Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice and came into existence after a two-year renovation to the building. Under the vision of Director Lisa Kim, the contemporary art space aims to cultivate social justice by facilitating individual leadership within international communities. For Kim, the inaugural show Perilous Bodies, “explores the inhumanity and injustice created by divisions of gender, race, class, and ethnicity”. The curatorial duo Abichandani and Becker set the tone for future programming as they weave together the perspectives of nineteen artists from around the world.

To access the gallery one must traverse a multi-tiered garden atrium and walk down a corridor past two works from the Ford Foundation’s permanent collection, Kehinde Wiley’s painting, Wanda Crichlow (Portrait of Catharina Both van der Eem) and Hank Willis Thomas’, I Am a Man. The exhibition begins at the end of the corridor just outside the entrance to the gallery with Barthélémy Toguo’s piece, Road to Exile. The installation incorporates a wooden boat piled high with bundles of patterned fabric and surrounded by a collection of overturned green glass bottles. The materials collectively evoke thoughts of displacement, transience, and provisional ingenuity.

Upon passing through a set of glass doors the viewer is immediately confronted with a hail of four hundred and eighteen miniature black missiles, cascading from the ceiling down towards the entryway, each missile a signifier of life lost. Mahwish Chishty’s piece Hellfire II named after the ballistic weapon, represents statistical symbolism and the persistent threat of mass violence within a community. Much of the work in the front room similarly addresses the topics of war, generational trauma, and societal policing. Curators Abichandani and Becker negotiate a balance between complex subjects and formal aesthetics in order to demonstrate examples of systemic racism, sexism, and oppression.

A series of loud strikes crack the placid murmur of the gallery and I turn the corner to investigate the source. I find a larger brightly lit space containing a multidisciplinary collection of photography, video, sculpture, painting, and fiber work. Each piece enjoys ample margins of empty space on either side which allow viewers a moment to pause and reflect. The element of respite is somewhat amiss in the front room, where Tiffany Chung’s wall-mounted text or Dineo Seshee Bopape’s video installation, Untitled (Winnie re-enactment) have the potential to be overlooked.

Three black billy clubs on mechanized hinges rap upon a wooden surface in Dread Scott’s installation, The Blue Wall of Violence to produce timed clusters of penetrating sound. The installation contains a row of six identical silhouetted shooting targets differentiated by date plaques above and the contents clasped in their outstretched mannequin hands. November 6, 1997, offers a Three Musketeers bar, February 4, 1999 hands over a wallet, December 25, 1997, presents a set of keys, mundane objects and a familiar gesture which presumably provoked the death of an individual. While processing the installation’s components I become aware that the wooden surface perpetually absorbing the emotionless impact of the billy clubs is, in fact, a pine funeral casket. The gravity of work sets in; a poignant elucidation of the value of black lives and systemic racism within American society.

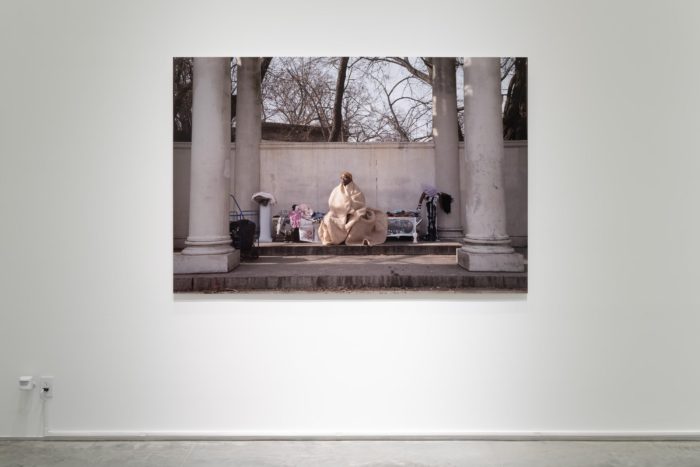

The works included in the exhibition intend to restore humanity to the homeless population, individuals who have experienced sexual abuse, civilians navigating wartimes, and members of society who systematically remain nameless or devalued. A record of handwritten accounts has magnitude in Jasmeen Patheja’s multipanel piece, Meet To Sleep. I Never ‘Ask For It’. In collaboration with Blank Noise, an organization Patheja founded and directs, the work exemplifies an artists’ ability to incite change and mobilize community through social activism. From David Antonio Cruz’s painting, inmysleeplesssolitudetonight, portrait of the florida girls to Nona Faustine’s photograph, Demeter’s Morning, justice lies within the dignified representation of their subjects.

I took a minute to collect my thoughts and process the exhibition on a black leather couch located outside of the gallery in front of the Kehinde Wiley portrait. Two women en route to a conference meeting stopped to admire the sizeable painting and as they turned to walk away one boasts, “that’s the same artist who painted Michelle Obama’s portrait”. My mind began to turn over the effectiveness of increasing the visibility of black, brown, queer, trans, disabled, and marginalized bodies in the public eye. At times change is painfully slow, a generational marathon which chips away at the cultural psyche. Perilous Bodies displays a continuity with the Ford Foundation’s mission to address the reality of social justice globally and opens up the gallery as a public space to meet, discuss, and learn. The exhibition will be on view at 320 East 43rd Street until May 11th, 2019. A public conversation with artists Nona Faustine, Thenmozhi Soundararajan, and Sara Rahbar about their work featured in Perilous Bodies will be held on Friday, April 12th from 6 – 8 pm. A curator-led tour will take place on Friday, May 10th in the gallery from 4 – 5 pm.