French-American artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), one of the most prominent and influential artists of the 20th century, left behind a body of work rare in its material diversity and emotional intensity, created over nearly seven decades. She produced a rich symbolic and figurative language, transposing the human body with architecture, animals, objects, and plants. All of Bourgeois’s images and forms articulate a range of universal human emotions, including desire, anxiety, loneliness, pain, and anger.

In 1982, Deborah Wye curated Bourgeois’s first retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The first retrospective in Europe, at Frankfurter Kunstverein, Germany, followed in 1989. Since then, large-scale solo exhibitions of her work have been staged in numerous museums the world over, and she participated in major international art events, including Documenta in Kassel (1992, 2002) and the Venice Biennale (1993, 1999), where she was awarded the Golden Lion for a living master of contemporary art. In 2000, at the onset of the new millennium, Bourgeois’s site-specific installation I Do, I Undo, I Redo was created as a special commission for the Turbine Hall. This monumental work, along with her 30-foot spider sculpture, Maman (1999), inaugurated the opening of Tate Modern, London.

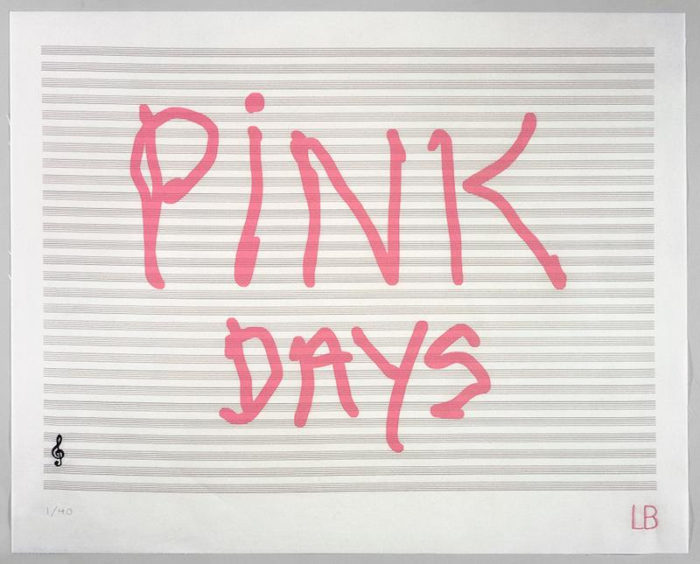

The exhibition at Gordon Gallery focuses on Bourgeois’s prints, mainly those created in the last decade of her life. They reveal, for the first time in Israel, the umbilical, Gordian knot between Bourgeois’s art and the medium of print. The title of the exhibition, “Pink Days / Blue Days,” is taken from a sculpture of the same name, created in 1997: variously-sized garments from Bourgeois’s wardrobe hang off of hangers attached to the “arms” of a central steel pole, such as a pink baby gown hanging from a bone. Addressing time and memory, among other themes, the sculpture preceded Bourgeois’s use of clothes and pieces of fabric in her late prints (on view in the show), in which she often embroidered her signature. The title also alludes to the expression “pink days,” written in pink over the pages of a music notebook, which Bourgeois made in 2008. For Bourgeois, the color pink represented femininity and happiness, while blue was symbolic of melancholy and depression. Blue could also represent the sky, which in turn expressed feelings of escape and of being overwhelmed.

The exhibition at Gordon Gallery is presented concurrently with Bourgeois’s solo show “Twosome” at Tel Aviv Museum of Art (curators: Jerry Gorovoy and Suzanne Landau).

Path to the Fundamental Problems

The Interrelations between Printmaking and Psychoanalysis in Louise Bourgeois’s Work

By Osnat Zukerman Rechter

Throughout the extraordinarily fertile artistic career of Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), one of the most prominent and influential artists of the 20th century, printmaking was a mainstay of her oeuvre. From 1938, the year in which she made her first print—a small lithograph entitled St. Germain—to final works created close to her death, prints were a testimony of her creative process and various mindsets. From the 1940s, Bourgeois kept a small press at home, which enabled her to make prints independently, alongside her collaborations with print workshops in the United States and Europe. Though primarily focused on intaglio, she ultimately worked in several different printmaking techniques (including lithography, screenprint, and digital prints). Printmaking, drawing, and their reciprocity formed the frame on which Bourgeois’s well-known sculptural works evolved, as well as the Cell installations she created later in life.

In the last decade of her life, following the incorporation of her own clothes in sculptures and installations since 1996, Bourgeois began using old handkerchiefs, bedding, and clothing as grounds for her prints. Subsequently, she created printed fabric books made from pieces of cloth, worn and characterized by their domestic use. Bourgeois’s late practice of working with and printing on fabric was connected to her first childhood experiences of art. As a young woman, she helped out in her family’s business—a tapestry weaving and restoration workshop—where she was often required to draw in the faded, blurred, or damaged elements of antique tapestries.

In 2012, the Museum of Modern Art, New York inaugurated a website dedicated to Bourgeois’s illustrated books and prints. Still underway, the site is intended to span some 4,000 works, most of them in the MoMA collection. This unique scholarly undertaking not only attests to the scope of Bourgeois’s print oeuvre, but also to the importance ascribed to her work in this medium by such a dominant, highly esteemed museum. The site is a natural continuation of a long collaboration between Bourgeois and Deborah Wye, Chief Curator Emerita of the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, at the Museum. In 1982, Wye curated Bourgeois’s first retrospective at the MoMA, which accelerated her acceptance and international success, as well as the first retrospective dedicated to Bourgeois’s prints in 1994. Another exhibition centered on Bourgeois’s prints is scheduled to open at MoMA in September 2017.

Due to the scope of Bourgeois’s print work, and since this medium was present in most stations of her artistic life, printmaking may be regarded as the “path to the fundamental problems” in her oeuvre, to paraphrase Nietzsche’s assertion in Beyond Good and Evil, that “psychology is once more the path to the fundamental problems,”1 in a paragraph where the philosopher emphasized psychology’s mastery over all other sciences, thereby undermining the view that science, philosophy, and ethics are founded on rationality, and stressing the unconscious facet underlying our perceptions. This paraphrase functions here as a point of departure for reflection on the unique relation in Bourgeois’s art—”the premier psychoanalytically oriented artist of modernity,” as Donald Kuspit called her—between printmaking and psychoanalysis:2 on the one hand, reference to the recurring themes in her prints—animals, figures, spiders, spirals, body parts, flowers, and architectural structures—as coding an emotional reality and its processing via psychoanalytical tools; on the other hand, the opposite—contemplation of fundamental issues pertaining to printmaking as a medium, such as artist-printer relations and the question of original and copy, in psychoanalytical terms, via Bourgeois’s work.

In 2012 an exhibition of works by Bourgeois was staged at the Freud Museum, London. The infiltration of Bourgeois’s works, with their formal symbolism and emotional intensity, into the space in which the founding father of psychoanalysis lived and worked during his final year, after he fled Vienna in 1938—a house that contains his belongings, collections and library—generated an exciting, thought-provoking dialogue and a rare encounter between the two. Thus, for example, Bourgeois’s renowned bronze cast, Janus Fleuri (1968)—a type of hybrid sexual organ, a cross between limp-male and enlarged-female genitals, duplicated and fused into one—was suspended over Freud’s famous couch. The installation of Bourgeois’s works at the Museum animated Freud’s objects and awakened them from their stasis as fixed museum exhibits.3 The show was curated by Philip Larratt-Smith, who edited the two-volume publication, Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed.4 The first volume, dedicated to images of Bourgeois’s work (mainly sculptures and installations), includes discussion of her oeuvre by various scholars and academics through the psychoanalytical prism, whereas the second volume exposed, for the first time, a selection of “psychoanalytic writings” she had written mainly between 1952–1966, years in which Bourgeois underwent therapy.5 These writings were discovered in her Chelsea home in New York City: two boxes at the beginning of 2004 and two more in early 2010. Most of them were written and scribbled on loose sheets and slips of paper, and they contain her thoughts, fragments of self-observation, descriptions of dreams, passions, aggressions, and anxieties, as well as reference to psychoanalysts whose writings she read.6 According to Larratt-Smith, “Bourgeois’s psychoanalytic writings elucidate the interconnections between her own psychoanalysis, her readings of psychoanalytical literature, her eccentric artistic output, her symbolic relationship to materials, and her formal invention.”7

Bourgeois’s prints invite contemplation of these interrelations from a different angle and with different emphases. The printer functions as a mediator between the artist’s concept, its execution on the printing plate, and the final product, so that another person, other than the artist, is involved in the process and can influence it. Much like the psychoanalyst, the printer helps extract the image from its raw (unconscious or near-conscious) state and transform it to another, processed state. Printmaking also implies work in a continuous series format. The printing processes are rife with interim states and trial proofs, good and bad, clean and dirty. In etching, in particular, the plate remembers and bears the signs and symptoms of the various work done to it, qualities which are pressed onto the surface of the paper without the artist or the printer having full control over them.

For Bourgeois, printmaking seems to have been a way of life, just as art, according to Donald Kuspit, was an autobiography for her.8 In addition to the printing press she kept at home and the prints she created in various workshops, twice in her life Bourgeois opened shops in which prints were part of her inventory. The first one, a gallery she opened in Paris in 1938, also had a crucial impact on the ensuing course of her life. It was there that she met Robert Goldwater, a Jewish-American art scholar who was in Paris conducting research for the publication of his doctorate dissertation, “Primitivism in Modern Painting.” After a brief courtship that same year, Bourgeois married him and moved to New York. Eighteen years later, in 1956, Bourgeois opened Erasmus Books and Prints in New York.

The format of a print artist’s book emphasizes an often narrative sequential practice, highlighting the relationship between word and image. Moreover, it brings the visual effect typical of printmaking into sharper focus when the written word is reversed, becoming its own other. Bourgeois created her first illustrated book at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17 in New York. Titled He Disappeared into Complete Silence (1947), it contained nine plates accompanied by short, enigmatic texts which revealed, as noted by Marie-Laure Bernadac, complex feelings, such as the fear of being abandoned.9 The images are all geometric, elongated, and reminiscent of skyscrapers and ladders. According to Bourgeois, “My skyscrapers are not really about New York. Skyscrapers reflect a human condition.”10 The rectangular space resulting from the embossment of the plate—the matrix, the mother—onto the moist paper delineates the image, capturing it therein, while at the same time engulfing and guarding it; at once aggressive and protective, much like the relations between parent and child. The plate marks, which are the memory of the matrix, function as a cell or a receptacle, a dominant motif in Bourgeois’s work.

In addition to the book, Bourgeois created numerous other prints during this period, including an early, geometric version of the she-spider, Araignée (1948). It is interesting to consider the link between the geometric structure and the organic motifs in Bourgeois’s work via the term “dynamic.” In the context of late-19th-century psychoanalysis and psychiatry, dynamic was the opposite of “organic,” rather than of “static.” The idea of the “dynamic disease” involves an assumption of the unconscious and the incessant effort to keep certain psychological contents distanced, namely – repressed. Hysterical paralysis, for instance, is a traumatic condition. It results from unconscious mental activity, hence it is not organic but dynamic. Certain phenomena of memory loss are likewise dynamic, and do not originate in an organic problem. In Bourgeois’s works, the fusion between motifs, such as figure and object, as in the painting Femme Maison (1946–47) or the sculpture Femme Couteau (1969–70), or between organic and inorganic forms, releases repressed, dynamic, disconcerting contents.

French neurologist, Jean-Martin Charcot, with whom Freud learned the technique of hypnosis at La Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, was the first to discuss dynamic manifestation.11 Historical photographs from the late 19th century present Charcot demonstrating dynamic manifestations of hysteria, a condition perceived as predominantly female, to his students. One of the postures of physical distortion documented in these photos was an arching of the body backward. The arch is both an organic and a geometric-architectural motif. In 1993 Bourgeois transformed the hysterical backward arching movement into a shiny bronze casting of a headless male (rather than female) body, Arch of Hysteria. In Triptych for the Red Room (1994), comprising three large-scale prints, two figures, male and female, arch backward intermittently. The arching movement against the blue backdrop may be regarded as a sexual role playing between them. In a print she created during the last year of her life, an entire house became an organic unit, a cell, subordinated to the power of an unconscious mental activity which made it curve into a hysterical arch (The Curved House, 2010).

One of the fundamental metamorphoses of the spider image, a pivotal, iconic image in Bourgeois’s oeuvre, was from an angular to an arched-curved state. In her illustrated book Ode à Ma Mère (Ode to My Mother, 1995), which included nine plates and text, and blended French and English, like all of her writings, Bourgeois explained why she chose this metaphor to represent the mother: “parce que my best friend was my mother and she

was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat and useful as an araignée. She could also defend herself, and me, by refusing to answer ‘stupid,’ inquisitive, embarrassing personal questions.”12

Following her mother’s death from illness in 1932, the 20-year old Bourgeois attempted suicide, throwing herself into the Bièvre river—hence, maternal protection, for Bourgeois, also involved separation, abandonment, a harsh and jolting experience of loss. The mother-spider appears in all nine plates. In many of them, she seems vulnerable and fragile, in contrast to Bourgeois’s monumental sculpture Maman. It was, in fact, Bourgeois who never ceased asking herself “stupid,” embarrassing questions, and digging into the depths of her soul via psychoanalysis. Protection against these questions may be deemed, primarily, protection of herself against herself; the rebirth of herself as both daughter and mother.

Bourgeois’s return to the old fabrics and their use in printmaking, which, in itself, is founded on a logic of repetition, is highly significant, calling to mind the game of disappearance and return, Fort/Da, played by Freud’s grandson, and described in his groundbreaking essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” (1920): The child had a wooden reel with a piece of string tied round it, and would throw it until it disappeared from sight in one of the corners of the room, uttering an exclamation which Freud identified as the German word “fort” (gone); he would then pull the reel again by the string while exclaiming “da” (there or here). Freud linked this repeated game to states in which the infant’s mother was away, and interpreted it as the child’s cultural achievement, as he overcame his fear of separation and allowed his mother to go out, to draw away from him. The child, Freud argued, repeated an unpleasant experience through the game and rectified it, so to speak; he compensated himself by transforming it into a game which he could control.13

Bourgeois’s mother, as well as childhood memories from the family tapestry weaving and restoration workshop associated with her, recurs in her work, often symbolized by the acts of weaving and spinning of threads or [cob]webs. Bourgeois’s illustrated books, Ode à Ma Mère and Ode à la Bièvre (2002)—a single copy entirely made of fabric (and editioned in 2007), which holds 25 compositions dominated by the color blue—both reconnect the artist to her mother through the image of the spider and the blueness of the river in whose waters she desired to sink. The books allude to the protective-pleasant “pink days” her mother imprinted on her, as well as to the blue, unpleasant ones, associated with the mother abandoning her.

The important series Hours of the Day (2006) is a song of praise to cyclicality and repetition: 25 printed, embroidered cotton panels, whose recurring motif is the music paper pattern in the background and a round 24-hour clock printed on it in red. The hands of the clock change from one print to the next, as do the sentences written by Bourgeois, added next to the clocks, partly in French, partly in English. In the essay “Freud’s Toys,” written by Bourgeois in response to the Freud collection exhibition presented in New York in 1989, she maintained that Freud lacked visual sensitivity,14 and that although he collected art objects and antique sculptures, he understood neither the language of art nor artists; they were all toys and case studies to him. The resistance to Freud, and possibly to psychoanalysis in general, may be construed as an integral part of her therapy, but in Bourgeois’s case, it seems to reflect more than that.

In the heartrending series Topiary: The Art of Improving Nature (1998), Bourgeois addressed the concept of pruning and felling the hollowed body as a therapeutic act, spurring it for budding and renewal, much like a plant. In some of the nine compositions, she drew a headless body encased in the shell of its garments with a fine drypoint line; its knee and shoulder joints are accentuated with pink stumps, which could be foci of regeneration for its missing parts. The Bourgeois family had suffered many injuries, to body and mind, as noted by Meg Harris Williams. Her elder sister had a prosthetic leg, which appears in this series as well as in other works; her young brother spent the last years of his life in a mental institution; her father was injured in World War I; and her mother, who passed away at a relatively young age, never fully recovered from a lung condition likely caused by the Spanish flu which spread through post-war Europe.15

Against nature’s forces of destruction and decomposition, Bourgeois harnessed a reverse logic, which deviates from psychoanalysis, and belongs to the very same nature. As a focal point of creation and renewal, she proposed the fundamental path: regeneration and eternal recurrence through art, yet one which may be regulated via collaboration with the other and through the fusion of word and image in print.

Notes

- Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Volume Twelve: Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Helen Zimmern (Edinburgh and London: T.N. Foulis, 1909), 34, para. 23.

- Donald Kuspit, “Louise Bourgeois in Psychoanalysis with Henry Lowenfeld,” in Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed, Philip Larratt-Smith (ed.) (London: Violette Editions, 2012), 25.

- The exhibition also underscored biographical similarities: In 1938, for instance, Bourgeois, like Freud, left her hometown Paris.

- The book was produced following an exhibition by that name curated by Philip Larratt-Smith at the Fundación PROA, Buenos Aires (March-June 2011), which later that year traveled to São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

- In late 1951 Bourgeois entered therapy with Dr. Leonard Cammer, but soon after switched to Dr. Henry Lowenfeld, whom she saw intensely from 1952–1966, and then less so until his death in 1985.

- Including Sigmund Freud, Marie Bonaparte, Melanie Klein, Anna Freud, Karen Horney, Otto Rank, Carl Jung, Bruno Bettelheim, and many others.

- Philip Larratt-Smith, “Introduction,” Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed, Volume II: Psychoanalytic Writings, 14.

- Kuspit, 18.

- Marie-Laure Bernadac, Louise Bourgeois (Paris: Flammarion, 1996), 43.

- Ibid.

- Henri Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry (New York: Basic Books, 1970).

- The full text in its original French version and in English translation is available at the MoMA website documenting Bourgeois’s illustrated books and prints.

- Sigmund Freud, Beyond the Pleasure Principle in A General Selection from the Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. John Rickman (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1980).

- The exhibition “The Sigmund Freud Antiquities: Fragments from a Buried Past” was staged at the State University of New York, Binghamton, and was accompanied by a catalogue: Sigmund Freud and Art (Binghamton and London: SUNY and Freud Museum, 1989). Bourgeois’s review was published in January 1990 in Artforum, vol. 28, no. 5, 111–13.

15. Meg Harris Williams, “The Child, the Container, and the Claustrum: the Artistic Vocation of Louise Bourgeois,” in Louise Bourgeois: The Return of