Joe Terrill: Once Upon A Time: Paintings, 1981–2015, NYC

September 10 – October 23, 2021

All images courtesy of Ortuzar Projects

Ortuzar Projects is pleased to present Once Upon A Time: Paintings, 1981–2015, the first solo exhibition of artist Joey Terrill in New York in forty years. A second-generation Los Angeles native, Terrill has critiqued Chicanismo and explored its cultural relationship to homosexuality over a four decade career—in paintings, drawings, zines, and collage. Particularly since testing positive for HIV in 1989, Terrill has directly addressed his status as a queer Chicano both in his art and his professional work as an HIV advocate.

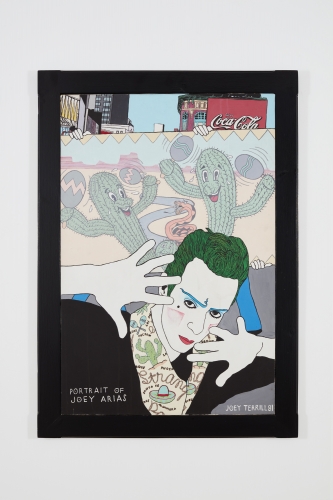

Engaged in the nascent Chicano Power and Gay Liberation movements since the early 1970s, Terrill was also exposed to diverse, overlapping creative scenes in California from a young age. Drawn to Sister Corita Kent’s visual language—which radically merged progressive Catholicism and Pop Art—Terrill attended Immaculate Heart College, where the art department was staffed by her former students. At the same time, he participated in the burgeoning Chicano avant-garde, absorbing influences ranging from ASCO’s guerrilla performances to Luis Valdez’s political El Teatro Campesino, and he exchanged “mail art” through Ray Johnson’s Correspondence School. His early style references Mexican retablos, Pop art, fotonovelas, and twentieth-century comics, while his later, more technical paintings trace contemporaneous developments in photorealism and Conceptual art.

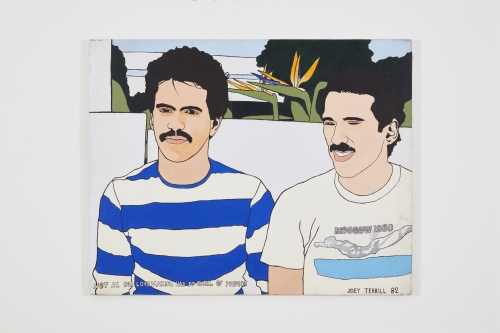

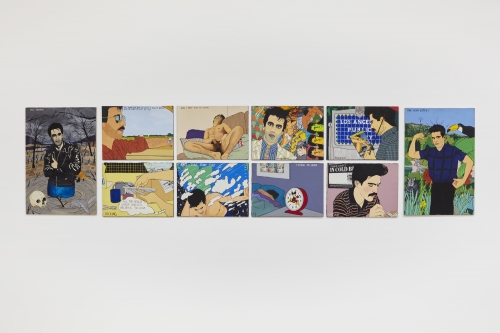

The exhibition features a selection of eleven acrylic-on-canvas works—including multi-panel pieces—drawn from two distinct bodies of work. The major three-part series Chicanos Invade New York, 1981, shows Terrill in the company of fellow Angelenos navigating New York City in the wintertime: preparing tortillas from scratch in a Soho loft, and seeking nourishment after a visit to the Guggenheim. The paintings were originally presented at Windows on White Street, in the storefront of Julius Blumberg, Inc.

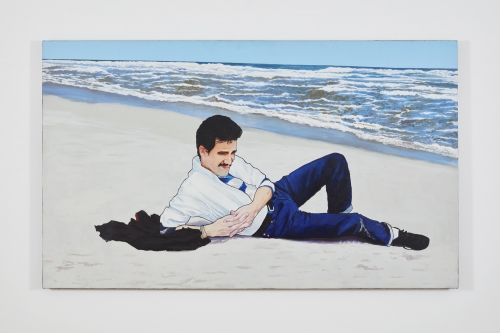

Terrill’s early work captures intimacies between friends and lovers at the start of the AIDS crisis, in episodic, droll, and confessional images that expand barrio culture’s heternormative notion of La Familia through the particular development of maricónography—a term coined by scholar Robb Hernández, meaning the distinct visualization of a queer or gay Chicano identity. In the torturous series Breaking Up / Breaking Down, 1984–85, or the small solo canvas Not All Our Lovemaking Had to Smell of Poppers, 1982, Terrill casts himself as the protagonist of an absurd, tragicomic telenovela. Following his own HIV-positive diagnosis—shortly after the FDA’s approval of azidothymidine (AZT)—Terrill’s painting technique shifts away from his characteristically flat style, approaching a kind of magical realism. The shadow and greater depth in Remembrance, 1989, a stylized portrait of Terrill and then-boyfriend Robert Ward gathering birds of paradise flowers among thorned agave and succulents, comprise a memento mori melding portraiture, landscape, and still life. Remembrance commemorates the anticipated death of the artist, his lover, and their many companions, mentors, and peers.

After 1990, Terrill’s paintings carefully reproduce images that document scenes of daily life in his community, as in the suite of works derived from the decadent Halloween costume parties thrown at his Los Angeles home between 1989 and 1993. In Jeff, Victor, Luiz and George, 1992–93, two statuesque partygoers crowned in flowers—dressed as the Frida Kahlo double self-portrait, Las Dos Fridas (1939)—gaze plaintively out of the picture plane, partially sandwiched by a Fellini-esque pair in open-mouthed laughter. By working retroactively from his own 35mm photographs—sometimes after those depicted have passed—Terrill bridges the tension between the facticity of the archive’s evidence and sensual, embodied experience. Through a kind of memory-memorial painting, or indeed storytelling, Terrill revitalizes a personal history strongly colored by loss and long threatened by erasure. His recent paintings picture a world after survival—where the possibility for humor, even joy, unexpectedly remains.

Joey Terrill (b. 1955) lives and works in Los Angeles, California, where he is Director of Global Advocacy & Partnerships for the AIDS Healthcare Foundation. As a high school volunteer for “La Huelga”— the farmworkers’ unionization movement, led by Cesar Chavez—Terrill learned the grassroots activism and skills he used a decade later as AIDS ravaged Los Angeles. Through his involvement with the Metropolitan Community Church, the Gay Community Center, and the “Gay-In’s” at Griffith Park in the 1970s, he befriended fellow queer Chicanx artists Mundo Meza, Gronk, Teddy Sandoval, Robert “Cyclona” Legoretta, Jef Huereque, Victor Durazo, Jack Vargas, Diane Gamboa, and Pattsi Valdez, among others. His solo exhibitions include Just What is it That Makes Today’s Homos So Different, So Appealing?, ONE Gallery, West Hollywood (2013); Worlds of Art (with Theresa Rojas), Ohio Union, Ohio State University, Columbus (2013); Chico Moderno, Norris Fine Art Gallery, Los Angeles (1993); Gronk & Joey, Score Bar, Los Angeles (1984); and Chicanos Invade New York, Windows on White Street, New York (1981). His work has featured in the institutional surveys ESTAMOS BIEN–La Trienal 20/21, El Museo Del Barrio, New York (2020–21); Touching History: Stonewall 50, Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs (2019); Through Positive Eyes, Fowler Museum, University of California, Los Angeles (2019); Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., Museum of Contemporary Art at Pacific Design Center and ONE Gallery, Los Angeles; and ASCO: Elite of the Obscure, A Retrospective, 1972–1987, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2011).