The salient dialogue pertaining to the relationship between social politics and biology is vital with the expeditious increase of scientific innovations catalyzed by the prevalence and prominence of technology. With such rapidity in advances, it’s indispensable to take the time to confront and scrutinize the multi-faceted perspectives that question its humanity. Utilizing art as a means to create this imperative analysis, Cured, Radiator Gallery’s most recent exhibition presents works by five motley artists who share the commonality of revealing their relative lens and stance in order to efficaciously evoke these necessary discourses.

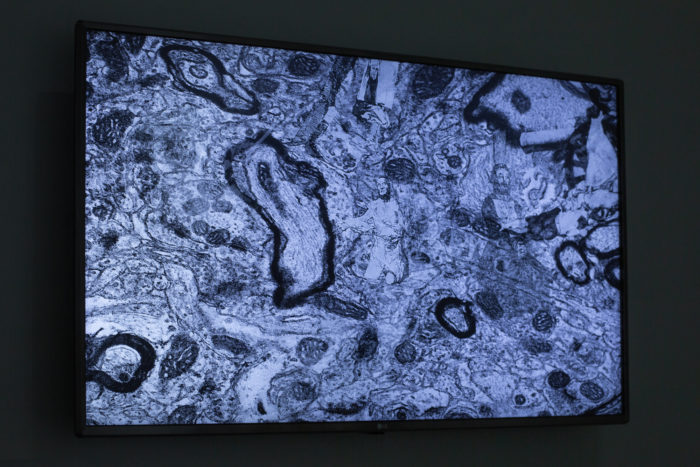

Upon entering the space, the viewer is first introduced to an adjoining room on the right with a video piece and a diptych of framed sculptural episodes by the artist Pablo Garcia Lopez. On one side of the wall, is a one-minute video—The Coming Age of Military Neuroscience—that projects dramatic audio with visuals of microscopic images of brain cells accompanied by ephemeral, superimposed fragments of Goya’s Black Paintings. The demanding, sensorial excess is balanced and contrasted by Brainvolution I and II, an intricate manipulation of natural silk that deftly forms into an arrangement of figures and objects. Garcia establishes an erudite study and exploration of the interconnection between neuroscience, history and religion.

Walking into the main compartment of the gallery, Anh Thuy Nguyen’s sculpture, Carry on From Both Sides, stands at 5’3”: a metal frame with a curtain of vibrant, scarlet fabric and on the opposite side a fleshy, silicone skin. Bolstered by a metal structure that’s connected to the frame are shoulder pads with a similar palette of hues mimicking the grounded rectangular structure. Nguyen informs me of how the pads were shaped to fit her own shoulders and that when one situates themselves into the position of it being worn and buckled, they are forced into a crouching position—insinuating that they are to be carrying the weight of the frame. She further speaks to me about her struggles concerning preassigned identities fabricated by society and the oppression and hefty burden that this creates. Using the shoulder pads and frame symbolically, she filters her contemplations into a physical sculpture that initiates a conversation that is very much pertinent to the present political climate.

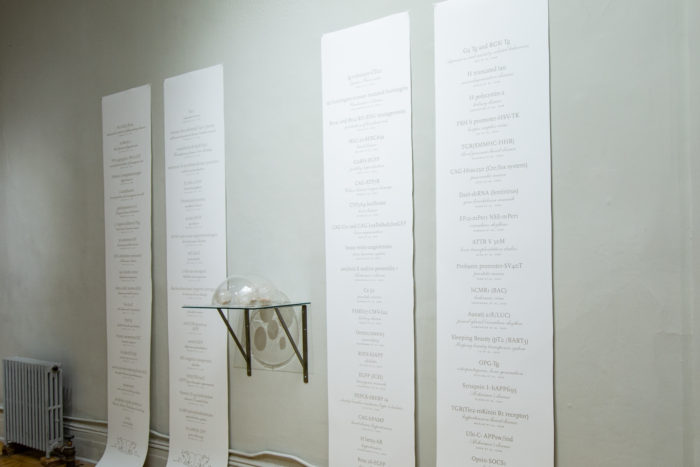

Following Nguyen’s piece, is Kathy High’s, Rat Models Banners, four digital prints that chronologically list the appellation for the transgenic lab rat (model code), their disease type, the scientific team and the year. Centrally located within the installation is the piece Burial Globes: Rat Models—five glass globes. Referencing the form of white blood cells, the lucid globes have a raised, coarse surface and are filled with the cremated ashes of five separate HLA-B27 transgenic rats. High notes how her installation acts as a memorial and serves the purpose to criticize the inhumanity of experimenting and creating life solely for the purpose to infest the beings with a disease: a predetermined life of sickness. The irony of finding medical cures for humans whilst treating rats cruelly evidence the hierarchy established and the superiority that we’ve bestowed upon our species. High’s reverent homage evokes a visceral brew of emotions as one ponders the normalcy of animal brutality veiled by a coat of human progress.

Across the memorial are twenty inkjet prints of cells precisely assembled into one large form of varying organic whites against a frame of stark blackness. Stem Cells, by Suzanne Anker, examines the “ethics of research involving the development, use, and destruction of human embryos.” Without knowledge of the prints representing magnified images of stem cells, one may find the shapes to be abstract ambiguities, but even with such information, there still maintains a cryptic tone to the representations. The pattern of disparate forms in repetition creates a pleasurable encounter to the eye and gifts the viewer with compelling and peculiar visual textures.

Across the memorial are twenty inkjet prints of cells precisely assembled into one large form of varying organic whites against a frame of stark blackness. Stem Cells, by Suzanne Anker, examines the “ethics of research involving the development, use, and destruction of human embryos.” Without knowledge of the prints representing magnified images of stem cells, one may find the shapes to be abstract ambiguities, but even with such information, there still maintains a cryptic tone to the representations. The pattern of disparate forms in repetition creates a pleasurable encounter to the eye and gifts the viewer with compelling and peculiar visual textures.

The exhibition concludes with Eva Petric’s MINDing the Collagen, a diaphanous veil of lace casting a shadow of a mesmerizing web against the floor. Tree of Life, her sculpture grounded by a plinth, is placed right below the opening of the suspended, encapsulating textile—establishing a narrative and cohesive composition. A positive of a real human heart, preserved in formalin, sits on a crystal block and both are then contained by a crystal dome. The transparent structures have engraved whimsical forms that mirror the fragile patterns found in the heart and lace. Using the metaphor of a tree as a reference to the human heart, Petric ponders the concept of a heart having the capability to exist outside of a body; she questions how life can grow out of this and what life means in its purest form. Petric also mentions that the installation was supposed to be supplemented with recorded audio of blood in a human heart, but this, I wasn’t able to experience as the crowd of people were either too loud or it was not playing (I wasn’t able to discern whichever was the case). Nevertheless, her immersive installation is enjoyable and would be quite magnificent to experience on a larger scale or in a more expansive space.

With art acting as a purveyor of rumination, Cured provokes alternative viewpoints of scientific developments and the effects or ramifications that may ensue from stated growth. Despite the slightly tight space, Tansy Xiao (the curator) successfully arranges the pieces so that they all work symbiotically with one another whilst still maintaining a sense of individuality. If you have yet to see the exhibition, I suggest you pop into LIC and into Radiator Gallery (the show will run until the 11th of August).

Writing by Ilsy Jeon

Photographs courtesy of Radiator Gallery