Noah Becker: Real & Imaginary at Not For Them Studio

28 Locust Street, Brooklyn, NY

February 22 – April 1st, 2024.

What does it mean to have a twin? When Gucci’s then-Creative-Director Alessandro Michele staged the “Twinsburg” show in September 2022, he wrote in the show notes: “Almost a rift in the idea of identity, and then, the revelation: the same clothes emanate different qualities on seemingly identical bodies. Fashion, after all, lives on serial multiplications that don’t hamper the most genuine expression of every possible individuality.” The runway’s soundtrack includes a voice that repeats the manifesto: “I am not a Xerox. I am not a clone, a duplicate, a copycat, a second scoop on the ice cream cone.” I wonder if we can say the same thing about portraits.

At Not For Them Studio, artist Noah Becker indulges in the loss of singularity. Through a series of recent oil paintings, most of which are double portraits of twin-like figures, Becker renders individual identity dubious. ‘Likeness’ in life and art becomes more than an instrument of duplication, eliciting the question: Is it possible to understand oneself without the representation of likeness or the likeness of representation?

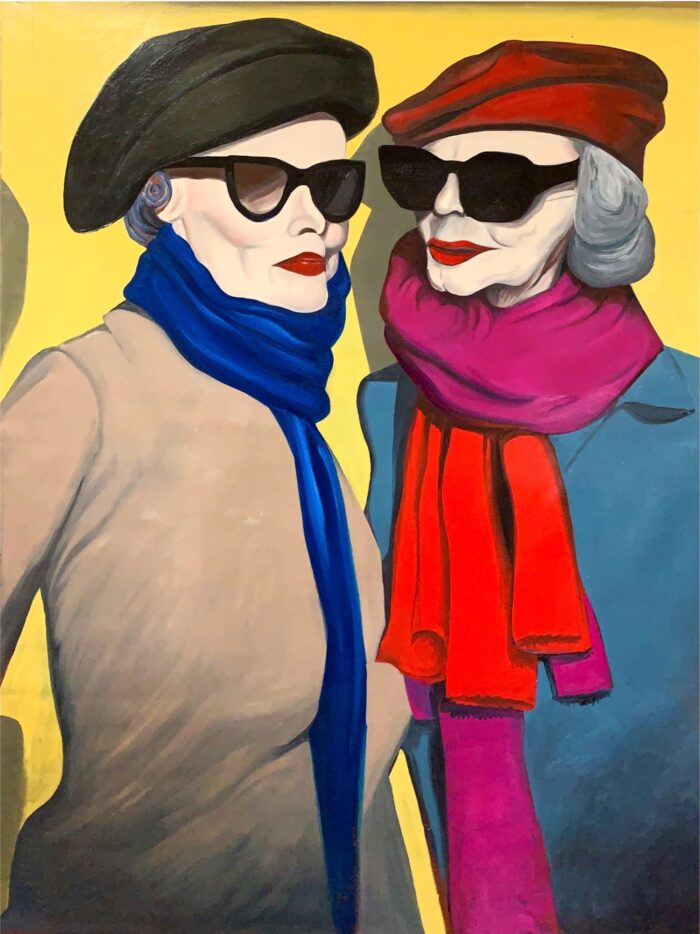

To echo the ambiance of the well-lit Brooklyn loft, all the paintings—unstretched with color-washed edges—are pinned to the wall; this mode of display imbues the portraits with the decorative, textile quality of printed silk scarves, which is especially evident in Flower Dream (2023). The striking elegance of these paintings further enhances this visual exuberance: Becker navigates the syncopation of saturated complementary colors with an incredible amount of control. The tonal waltz of purple, orange, green, and red possesses the distinct aesthetic charm of vintage magazine covers. The influence of post-impressionist, old master, and 19th-century paintings is apparent through Becker’s brushwork and the angularity and austerity of the figures’ countenances. With their reciprocal gaze obstructed by tinted sunglasses, they are simultaneously confrontational and psychologically impenetrable.

In the double portraits, the subjects share a sense of inexplicable intimacy that oscillates between friendly and familial, occasionally with a hint of fleeting eroticism as seen in Two Figures (2023), in which the stoic figure in blue is like a phantasmagoric guardian. These ‘twins’ are similar enough but never identical. In Two Figures in Scarves and Hats (2023), the figure on the left has a fuller chin and more prominent cheekbones, while her more colorful counterpart is depicted with a cleft chin and appears slightly older. In Two Figures (Yellow Sweaters), both women have a beauty mark on the left side of their face, yet the figure on the right—smirking and cheekily posed—seems to be an intentional caricature of the figure on the left. By contrast, in Double Smoker (2023), the beauty marks are mirrored, as are the berets and shirt pockets. So are these figures look-alikes or two sides of the same person? If the latter, how do we know which figure is actual? We have now encountered an interpretive dilemma regarding the relationship between representation and duality.

Said dilemma, however, is not endemic to these ‘twin portraits’ but rather manifests more generally in the genre of portrait paintings. On the one hand, portraiture’s communication of identity hinges on the notion of ‘likeness’—the formal accuracy of representation. On the other hand, portraits suffer from the conceit of duplication. In “The Changing View of Man in the Portrait,” John Berger writes: “We may still rely on likeness to identify a person, but no longer to explain or place him. To concentrate upon ‘likeness’ is to isolate falsely. It is to assume that the outermost surface contains the man or object, whereas we are highly conscious that nothing can contain itself.” One’s portrait is almost like a twin—an impressively deceiving trompe-l’oeil in form and/or spirit, but never quite a replica. Therefore, it is not that I meant to neglect the one-person portrait, Figure in Profile (2023), but that its juxtaposition with other double portraits made me realize there is room to see it as a ‘twin portrait’ as well.

Real & Imaginary is a show that invites many interpretive possibilities. It somehow made me feel that each of us living in the digital age already has a twin. Our online presence allows a digital data set version of ourselves to be created, analyzed, accessed, and weaponized. A non-human twin, whose similarity with us we are reluctant to acknowledge, exists as a factitious shadow that purports to reveal our daily routines, preferences, and intimate thoughts. This exhibition confronts the inevitable absence of singularity in art and life alike while also revealing that it is through the small cracks—like the failed cloning or the misplaced beauty mark—that individual identity is affirmed time and time again.