A sculptor, a painter, a seamstress, a printmaker, Louise Bourgeois was not wedded to any particular medium. She was far more interested in the release of emotions. Her pieces emerge from an ongoing fluctuation between feelings of containment and liberation, compression and amplification, the urge to stitch things together and break things apart.

In 1982, when Bourgeois was 70, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a retrospective of her work. It was the first of its size that the museum had devoted to a female artist, and it was accompanied by a slideshow—along with a photo essay published in Artforum—that granted viewers a candid look into the life of an artist who had long kept quiet about herself. Titled “Child Abuse”, the photo essay revealed to the public the story of her father’s affair with her young governess, which left Louise feeling angry and betrayed by the adults in her life.

Following the death of her father in 1951, Bourgeois entered into Freudian analysis, which she remained in for the next thirty years or so. Fittingly, childhood memories were hugely significant to Bourgeois’ work. Memories of her mother, in particular, as a tapestry weaver and protector, led to a series of large, now iconic spider sculptures.

However, fundamental to the process that brought Bourgeois’ art to fruition was the general anxiety she lived with on a daily basis. The condition plagued and infuriated her and was the stressor that regularly compelled her to seek relief by creating art. In a 2016 interview with The Guardian, Bourgeois’ long-time assistant, Jerry Gorovoy, was quoted as saying, “If she worked, she was OK. If she didn’t, she became anxious. . . and when she was anxious she would attack. She would smash things, destroy her work.”

Gorovoy was actually tasked with removing completed pieces from Bourgeois’ studio before she had the opportunity to destroy them. As he remarked In a 2014 interview with Vulture, “Louise was exclusively interested in the piece that she was working on. She felt that once a piece was completed, it had served its purpose, and she wanted to move on. . . she was more interested in expressing the intensity of the moment, the anxiety of that particular moment.”

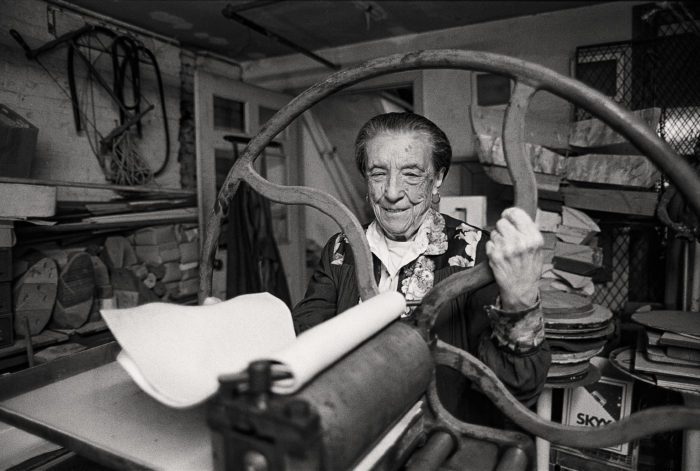

In 1938, following her marriage to art historian Robert Goldwater, Bourgeois moved from her hometown of Paris to New York. While still in Paris, she had been dubbed a sculptor by the multimedia artist Fernand Léger. However, although she would go on sculpting, Bourgeois’ spent her early days in the city working on a smaller scale. And at the Art Student League and Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17, she refined her printmaking skills, an expertise she would carry with her and utilize for the rest of her life.

Now on view at MoMA, Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait provides a look at her creative process through a focus on her later printed works in relationship to her larger oeuvre.

Bourgeois was taken with New York’s skyscrapers. In a 2007 interview with Richard Marshall for Whitewall Magazine, Bourgeois spoke about her first impressions of the United States and New York specifically, “I thought New York was beautiful, a cruel beauty in its blue sky, white light, and skyscrapers. I felt lonely and stimulated.”

Two etchings framed in white entitled The Sky’s the Limit (1989-2003) evoke similar emotions, while perhaps hinting at America’s most iconic patriarchal structure. Brushed with watercolor and gouache in varying degrees of red, white, and blue, each print features a lone obelisk, which looks to be under construction. The floors, rounded in shape, look similar to discs between human vertebrate.

Just around the corner from these prints, in an adjacent room, is a sculpture entitled Figure (1954) made up of small wooden squares—painted a sky blue—stacked one on top of the other and encased by long planks of wood painted in white. A larger blue square tops the piece. Here too a spine is brought to mind as the skeletal structures of architectural and human forms seem to mirror each other in Bourgeois’ work.

Spiral Woman (1951-1952), a white, spiral stair-like structure, made up of painted wood and steel, picks up on these themes, while also making use of the spiral, a shape that Bourgeois understood as “an attempt at controlling the chaos.” The piece may also recall Nude Descending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp, an artist with whom Bourgeois was in contact.

Beside this sculpture is an engraving entitled Spiraling Arrows (2002) featuring a series of small, left pointing arrows spiraling inward, resulting in a larger, light-red, vaginal shape. Pink leading into red colors the four corners that surround the top and bottom of the spiral.

Bourgeois assigned different emotions to the spiral depending on which way it wound. Outward motion was related to ideas of “giving” “trust” and “positive energy, while a spiral that turned inward—like that of Spiraling Arrows—related to ideas of “tightening” and “retreating.” While all are universal concepts, she has attached them to women and the female form in unique ways.

Bourgeois liked to play with gender associations. In Arch of Hysteria, a work from 1993, she gave a presumed female disorder a circular, masculine form with a hanging bronze cast of Gorovoy. The headless body arches so that the fingertips nearly touch the toes and is suspended from an attachment at the stomach. Speaking of the piece, Gorovoy recounted, “Though usually hysteria is associated with women, Louise wanted to use a male figure, and I became her model. She wanted to prove that men could be equally hysterical.”

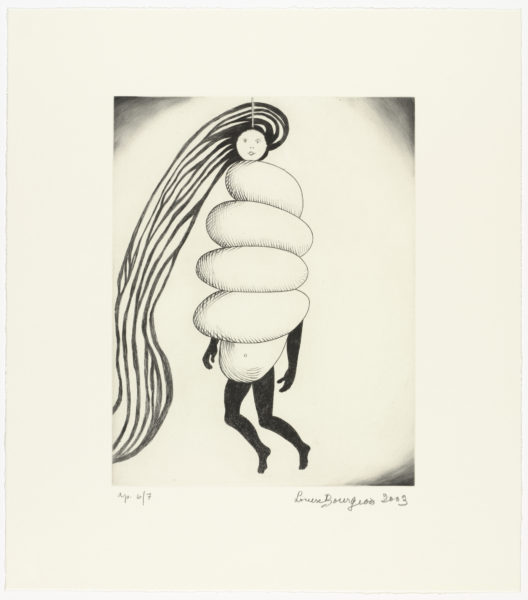

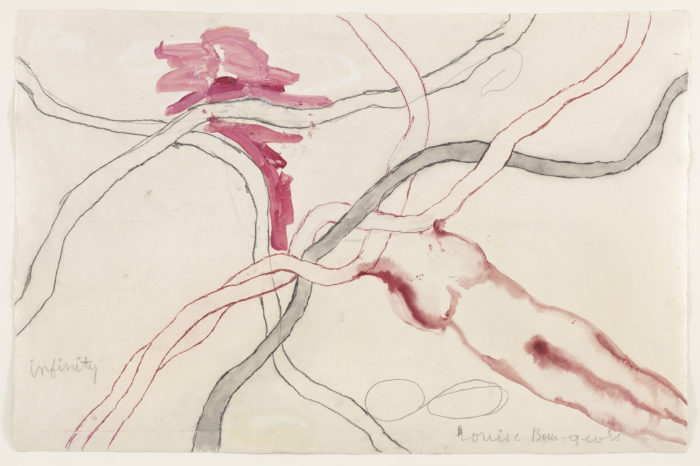

Arch of Hysteria is situated in the middle of the final room of the show, which is lined with a series of prints entitled À L’Infini (To Infinity), created in 2008. As notions of pain and gender seemed to have melted together and then frozen at the center of the space, a successive unravelling and knotting of sorts appears to be occurring around its edges.

Colored in reds, pinks, and grays, utilizing watercolor, gouache and pencil, À L’Infini feels both dreamlike and scientific. Not tautly hung or contorted, the human figures depicted along the walls fuse and float attached to loosely winding tied and untied strings, which are reminiscent of umbilical cords, chromosomes, and, of course, the threads Bourgeois’ mother used to weave together tapestries.

Led by Deborah Wye—who was instrumental in putting together Bourgeois’ 1982 retrospective—the curatorial team behind Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait has made expert use of juxtapositions. Recycled images and themes emerge with new meaning as one walks through each of the rooms and recognizes the art of Louise Bourgeois remains timeless.

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait

Through January 28, 2018

The Museum of Modern Art

11 W. 53rd Street

New York, NY 10019