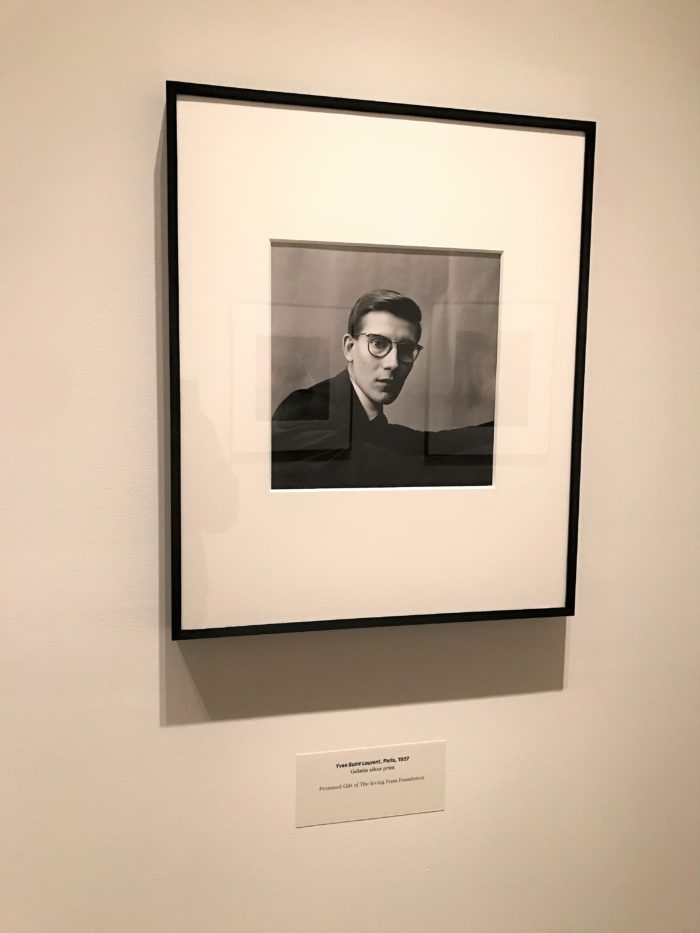

The exhibition of Irving Penn’s work currently on view at the Met spans the iconic photographer’s 40 years of work. From his early work at Vogue, in which notable names of the day including Picasso and Freud sat for their profiles, to his later exploration of indigenous cultures in Peru.

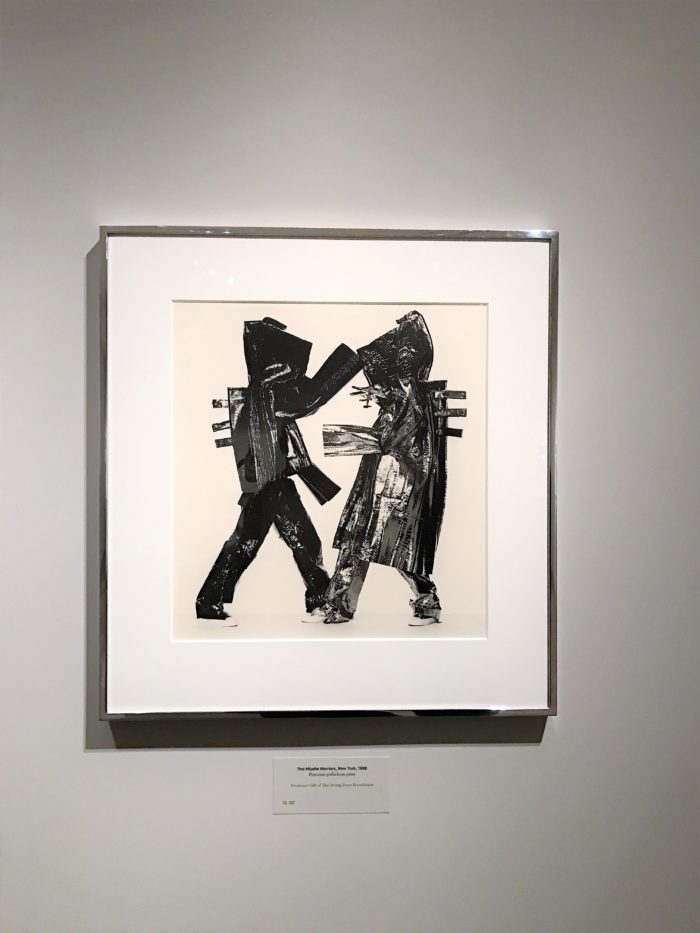

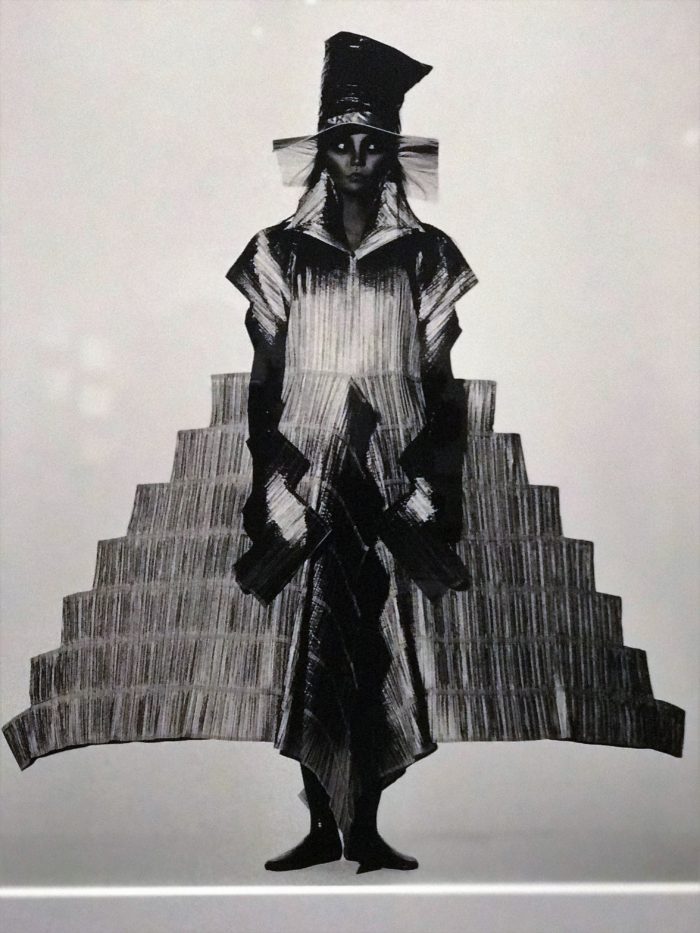

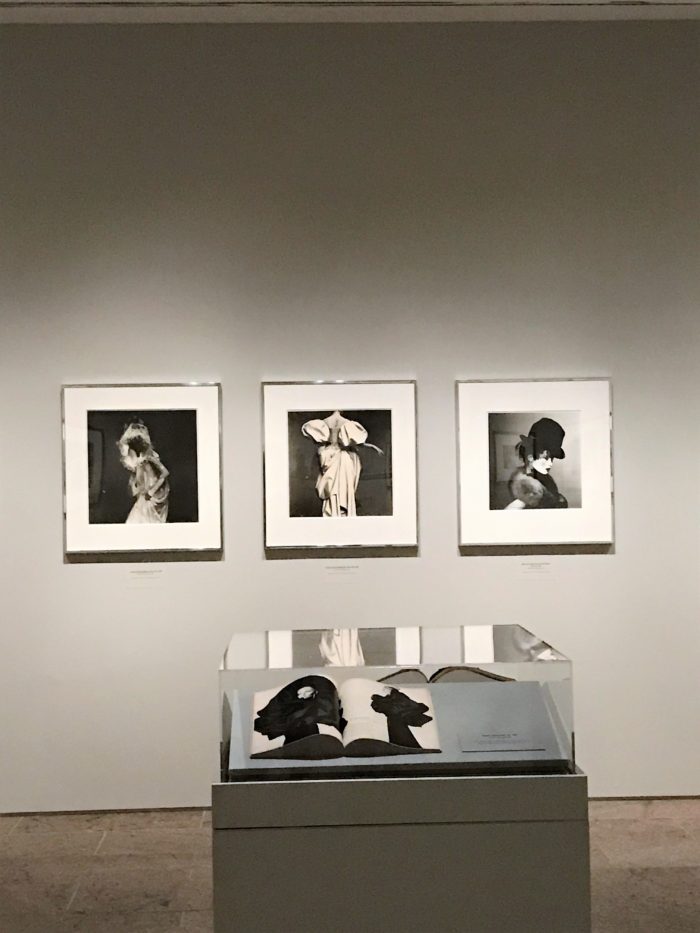

The exhibition is masterfully arranged by juxtaposed rooms each from a period of his development. Both large-scale photograph prints and books of Penn’s work display his wonderfully obsessive attention to the most minute of details. The juxtaposed work allows for an in-depth analysis of his techniques. Of particular note regarding his techniques are his use of the corner as a motif to magnify and foreshorten his sitter’s proportions. This became one of his most well known signatures. Of other note was his use of rough industrial carpet over crates to both frame the composition and position his subjects. Lesser known of Penn’s process is his exploration of the medium of photography itself. Using film processing he explored the negative images and exposure time of analog film. His subjects and an entire room are devoted to the body’s forms, most of which were female. The enlarged focus on breasts, stomachs, and thighs transformed the body into an almost unrecognizable albeit beautiful shapes.

Once he had established himself as a photographer of repute, he used his lens to explore the art historical subject of the still life. His beautiful, lush and immediate capture of fruits, seeds, bowls, glasses ignited his palette and at once shown and hid the grandeur of the simple objects in composition. The element of dynamism is apparent in his living and still subjects alike. What Irving Penn mastered and what the exhibit at the met captures is Penn’s knack for finding the sublime coexistence between stillness, sharpness, and movement.

His photographs transform the human body into landscapes, beautiful undulating terrains of light, shadow, mass and depth. His photographs to use the art term make wonderful use of chiaroscuro and a commanding gravitas which the exhibition demonstrates to magnificent effect. The show even has on display one of Penn’s first camera devices and one of his sloping backdrops.

What is particularly great about the exhibition is that it not only displays his fashion work for which he is well known but his lesser known explorations of culture, film process, and object in almost equal measures. And like all great art the collection of Penn’s prolific work allows for a time jump to a bygone era. As a colleague noticed, except to show the ceremonial dress of indigenous peoples, there is a noticeable lack of people of color. Far from a direct critique of the work itself, it serves to create a framework of the time in which Penn worked and to draw a line to contemporary racial politics of the today. As well as the road we have travelled and still have left to go.

Irving Penn: Centennial at The MET

April 24–July 30, 2017

by Daniel Ashley