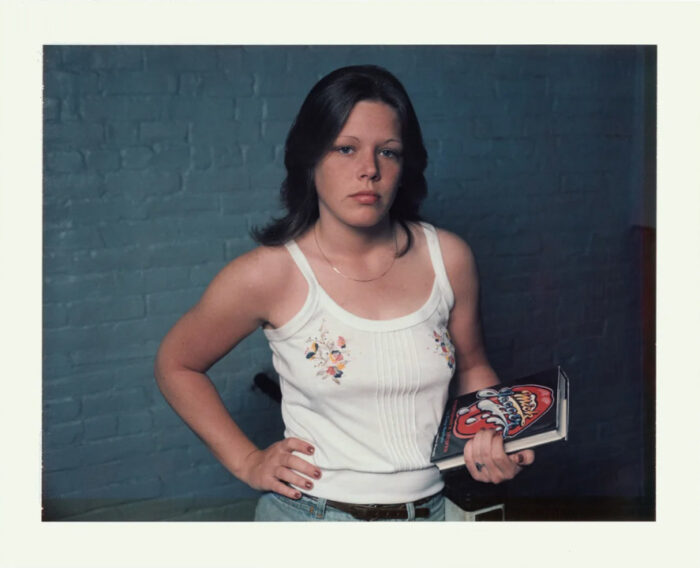

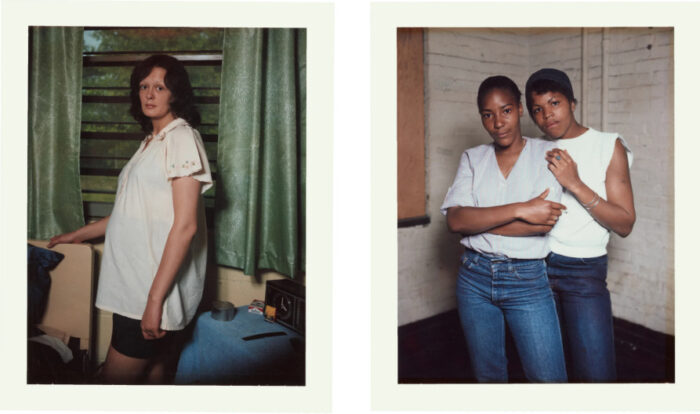

Jack Lueders-Booth’s book, “Women Prisoner Polaroids,” is distinguished by the intimacy of its 32 photographs, capturing inmates in personal, often homely settings. The women wear their own clothes, and their cells are decorated with personal items, creating a warm, college dorm-like atmosphere. This stands in stark contrast to typical prison portraits, reflecting a more humanizing approach to incarceration. Miriam Van Waters, the first superintendent at Massachusetts Correctional Institute Framingham, aimed to prevent inmates from forming their identities around their imprisonment, promoting a home-like environment by allowing domestic clothing and having un-uniformed guards.

Jack Lueders-Booth’s book, “Women Prisoner Polaroids,” is distinguished by the intimacy of its 32 photographs, capturing inmates in personal, often homely settings. The women wear their own clothes, and their cells are decorated with personal items, creating a warm, college dorm-like atmosphere. This stands in stark contrast to typical prison portraits, reflecting a more humanizing approach to incarceration. Miriam Van Waters, the first superintendent at Massachusetts Correctional Institute Framingham, aimed to prevent inmates from forming their identities around their imprisonment, promoting a home-like environment by allowing domestic clothing and having un-uniformed guards.

Founded in 1878 as a reformatory for women guilty of moral offenses, by the 1970s, the prison housed women convicted of minor crimes like shoplifting and sex work. Under Van Waters’ influence, the facility became a site for experiments in rehabilitation, aiming to reduce the psychological impact of incarceration. Jack Lueders-Booth arrived in 1977 to teach photography as part of his Harvard master’s thesis, intending to boost inmate morale and provide valuable skills. His involvement was timely, as another Harvard professor was looking for someone to lead a prison arts project at MCI-Framingham.

Lueders-Booth, with his daughter Laura, converted old cells into studios and darkrooms, teaching small groups of women to create photograms and eventually portraits. Initially, both he and the inmates were apprehensive, but trust developed quickly. Over seven years, he became a trusted figure within the prison, documenting the lives of inmates and producing photographs for various prison purposes. His work gained administrative approval and became a part of the prison’s visual culture, reinforcing his sense of contribution.

Lueders-Booth, with his daughter Laura, converted old cells into studios and darkrooms, teaching small groups of women to create photograms and eventually portraits. Initially, both he and the inmates were apprehensive, but trust developed quickly. Over seven years, he became a trusted figure within the prison, documenting the lives of inmates and producing photographs for various prison purposes. His work gained administrative approval and became a part of the prison’s visual culture, reinforcing his sense of contribution.

The book concludes with anonymous testimonies from the women, juxtaposing their vivid accounts of prison life with the serene images Lueders-Booth captured. This contrast underscores the complexity of their experiences, emphasizing that while they are prisoners, their identities encompass much more. Lueders-Booth’s photographs challenge the simplistic and often superficial labels imposed on incarcerated individuals, highlighting their humanity and the socio-economic factors influencing their lives.

The book concludes with anonymous testimonies from the women, juxtaposing their vivid accounts of prison life with the serene images Lueders-Booth captured. This contrast underscores the complexity of their experiences, emphasizing that while they are prisoners, their identities encompass much more. Lueders-Booth’s photographs challenge the simplistic and often superficial labels imposed on incarcerated individuals, highlighting their humanity and the socio-economic factors influencing their lives.