Where do we look for the antidote to the inevitable challenges and disenchantment of living in global metropolises? At Tutu Gallery, Land Language/Bahasa Bumi offers a place of refuge rooted in Javanese landscape and opens up a world in which nature’s intimate immediacy is materialized. Both Indonesian-born and New York-based, Megan Nugroho and Samuel Alexander Forest employ an engaging visual language of sinuous whiplash lines, prismatic geometries, and serene colors. In this conversation, as they speak about their places of origin, spirituality, and sublimity, the artists reflect on their creative journeys guided by a sense of connection with nature.

JW: The title of the show is Bahasa Bumi, or Land Language. What is the relationship between language, nature, and your work? Can you tell me about a moment when nature spoke to you?

MN: Sometimes the idea of language is quite literal in my work. I incorporate Javanese Sanskrit into these nature drawings. Some of these words have magical undertones, like the glyphs meaning “underground/hell.” I recently learned these words from my mom, who grew up studying it. For me, the organic-looking forms of these scripts are really beautiful, so it is another way of connecting the human with the natural.

I come from Jakarta, the largest city of Indonesia. For a country that is well known for nature, you barely get to see it in Jakarta. You see buildings all the time. After coming to New York, which is another metropolitan city, I found it so exhausting that I wanted to take a break from here once in a while. Now I actually really miss home, and I try to channel this feeling into my art by capturing the aura, magic, and beauty apparent in the country.

SAF: Like Megan, my family are also city people. I come from the second-largest Indonesian city. But ever since I was young, I have always dreamed of landscapes and wanted to be in nature.

I think the natural world teaches us the language of silence; it is a place where you learn to listen despite occasional loudness (like volcano eruptions). During a recent train ride to Boston, I was watching fall leaves through the window, and I started thinking about how I haven’t had the chance to actually go outside and hike this season. Tears just started streaming down my cheeks. I really wanted to be out there but didn’t have the chance because of having been busy.

JW: Busy making nature-related artworks!

SAF: Yes, it’s really funny, and I have indeed been thinking about the paradox of making these works without being able to be close to nature. In the same way, while my other works center on themes of care and the people in my life, I’m in the studio a lot, which keeps me away from these actual people.

JW: Megan, something that stood out to me about your drawings was the texture created by colored pencils – how long does it take to complete these works? What drew you to this medium, and how does it affect the way you express your subject matters?

MN: The smaller drawings of genital-like flowers can be done in a few hours. When I was doing my MFA program, I made really big works, and those would take much longer. Before the pandemic, I did a lot of printmaking, which I couldn’t do in the middle of the pandemic. I kept going with colored pencils because the medium is super accessible. The colors are really special and reminded me of how I’d use colored pencils in my childhood. The precision and meditative qualities are definitely a big part of this process too. Samuel and I both make work on paper, which also connects to the idea of language/writing that constitutes part of the show’s title.

JW: Samuel, you made abstract, miniature mountains for this show. How does this manipulation of scale affect the way we perceive the natural landscape? What is the significance of bringing nature into an indoor space in this way?

SAF: I made these mountains knowing that they would be shown here in this space, so I didn’t want to overtake the gallery space. I wanted to make sure that there is enough room for people to walk around the sculpture-drawings, experience them, and see all sides of them. I think larger installations lend themselves really well to giving viewers an immersive experience, whereas here, I wanted to challenge myself with the control variable of dimension in mind: How can I make smaller objects more appreciated? How can they still have the same effects that larger pieces would have? Just like how Megan said that drawing is a meditation, I feel that for me, the mountains are also a kind of meditation. I hope to convey this spiritual experience to others via these works.

JW: How do you situate the human in your work? What does this engagement with nature reveal about our human condition?

MN: For me, while the human body isn’t in every artwork, there is a constant theme of yearning for nature because I’m trying to figure out where humans fit within nature.

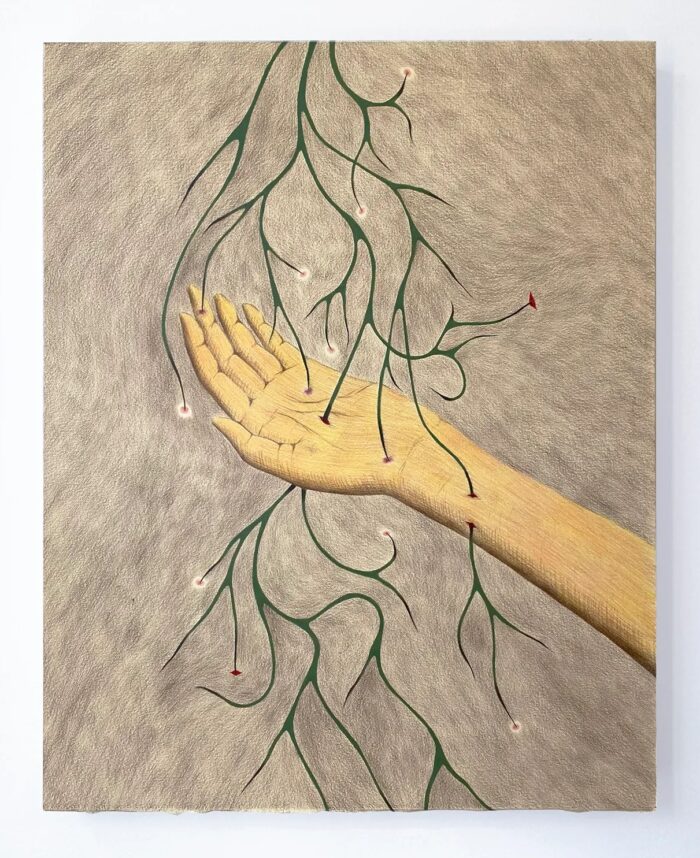

It is not always easy to mediate between plants and the human body. In Where roots turn into thorns, I am trying to combine thorns with a human hand, which results in the awkward-looking interpenetration of forms. But it is also a realistic depiction of the dynamics between us and nature: the wilderness is a precarious place where you can get hurt. When I first came to New York, I immediately noticed how amazing the parks are; even if you go hiking upstate, the hiking paths are great and–for the most part–safe, leaving people with the impression that nature is safe. But back home, nature isn’t as developed the way it is here and tends to be a little scarier. There are many stories and cautionary tales about supernatural forces or taboos.

For instance, in my work, I use a lot of green because in Indonesian mythology, the goddess of the sea wears the color green all the time, which is also the color of nature. Her spirit is in Java everywhere: She is known to rule over the South Sea, and people would associate her power with incidents of people going missing at the beach. She is known to be very attractive and beautiful, so she is able to infiltrate the powerful figures of the country through marriage. She is also associated with fertility. She is sometimes seen as a scary force and is very haunting. If you ever go to Java, you would see a lot of greens in hotels and in people’s homes as tributes to her power. Therefore, the relationship between human and nature is a complicated mixture of respect, protection, threat, and reverence, which I think also relates to Samuel’s work.

SAF: Yes, the danger that lies within the natural landscape reminds me of the fragility of the human condition. For instance, Krakatau is a representation of the 1883 volcanic eruption, which was one of the largest volcano eruptions in world history. It produced the loudest sound ever recorded and turned the sky orange in Europe. It was possibly the inspiration behind Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893). The mountain also dissolved with its own eruption and sank into the sea. Similarly, my lake crater sculptures entail looming danger because they are daytime and nighttime representations of the most acidic lake in the world–Kawah Ijen Crater Lake. Despite the alluring colors, I cannot imagine what would happen to the human body had they come into contact with the water.

But more importantly, the through line in all of my works is care, and I think of art-making as a practice of spirituality. In my practice, I had made replicas of rocks that I would come across on my hiking and climbing trips. The rocks that called to me are like journals through which I kept track of time, place, and the people whom I was with.