On a chilly winter evening, while at his studio at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, LMCC, Zac and I were once again in conversation: overlapping thoughts, ideas, and history. Ultimately as a foundation of storytelling –where this interview shares perspective and process. From self to work, at first through sculpture, a long time medium, followed by sound, simultaneously enveloping the audience. We dive further into “Beyond the Pale” and the undeniable links between borders that construct sovereign nations, delineate warfare, and continue to separate families to this day.

ZH: Zac Hacmon (b. Holon, Israel) is an artist based in New York. He was awarded the Foundation for Contemporary Art Emergency Grant 2020, Santo Foundation Individual Artist Award 2019 and the Cafe Royal Cultural Foundation Visual Project Exhibition Grant 2019. Hacmon received an MFA from Hunter College and a BFA from Bezalel Academy of Art (Israel).

EMD Eva Mayhabal Davis (b. Toluca, Mexico) is an independent curator, based in New York City, she collaborates with artists and creatives in the production of exhibitions, texts, and events. She is a founding member of El Salón, a meetup for cultural producers based.

EMD: Can you speak more about sculpture as your medium, as form and your goal with objects in space as interacting with audiences and beyond?

ZH: My father used to work with marble. He built memorial stones in Israel. And I used to work with him as a child, I was four years old and we would work in the cemetery. It was kind of surreal for me as a child to be surrounded by so many ׳people’ and yet it was so quiet. Of course, I wasn’t really doing anything because I was too young. But my father always taught me how to handle the marble, it’s principle and the secrets of working with matter that’s what I remember and it’s something that I take with me. In my sculptures you see it in the geometry, scale, and weight as they form themselves almost as a monolith.

I also studied industrial design, it’s had a huge impact on how I perceive the object. I went to study industrial design because I wanted to know where products come from. I remember one day, I was looking around realizing I was surrounded by products! The VHS, TV, computer keyboard and all the stuff that are part of who I am but I had no clue about how detailed and complex objects came to be. When I found out I left school, in the fourth year they asked me to design a remote control and a cellular phone. I refused. I didn’t want to be part of that industry which is responsible for a lot of the problems we have today. I didn’t want to make another mess produced object. I wanted to make one of the kind objects.

I was always fascinated by objects. They are a way to analyze society, you can learn about a place by its objects, it’s a kind of anthropology by observing the surroundings.

EMD: How do you want the audience to interact with your pieces?

ZH: I see myself as a sculptor but even more as an installation artist. For me the definition of installation includes the viewer. In Israel, I created an installation of a refugee bar called: ‘Aliyah Market’. The refugee crisis was happening in Israel and the questions on how and what we could provide as a government was very similar to the American: no status, no entry, close the borders.

By the time they closed the border there were already around 50,000 people in Tel Aviv and they had no status, their passports were taken away. They created their own communities and they set up their own bars. I did a year of research, going and sitting in these bars, I learned about what it represents to them. I did interviews too. I ended up creating this immersive installation of an Eritrean refugee bar. A typical Israeli person would never go there and would even be afraid to go there. In creating this installation, I relocated an environment so that the viewer confronted a lot of questions and basically, ask them to go beyond the pale.

EMD: Can you elaborate on the political positioning of the interactions that your work demands from the audience?

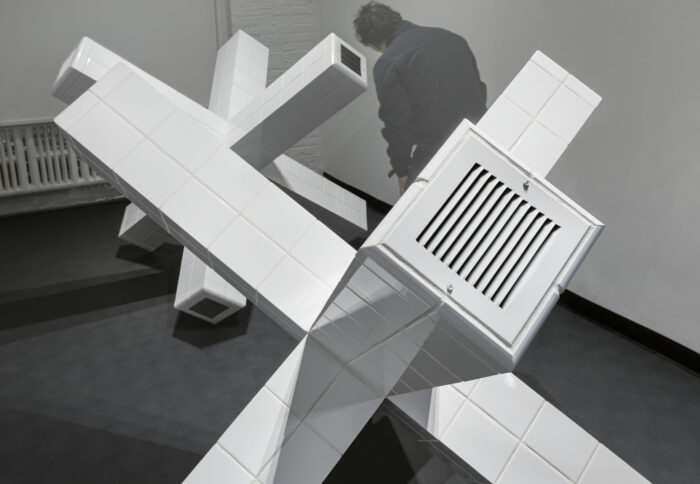

ZH: It’s about spaces, like the way the bar was set up to be familiar or welcoming while also uneasy and thought to be dangerous. For Beyond the Pale, the hedgehogs are not at all familiar but the tiles are and the sound is curious but then you have to listen.

It’s a launching off point to see and interact with barriers.

These hedgehogs are not a direct relocation of a site, they are a hybrid of sources, sites, and histories. I am fascinated with them because art is not something that I take for granted or something that I can claim to know. I am setting up a platform for people to interact: through looking at the object, observing with stillness… listening.

We are looking at the object and sometimes the object looks at us, the sculpture functions as a device rather than a passive object.

EMD: Why are you responding to the crisis that is happening along the border?

What triggered me the most was seeing the death maps by Humane Borders. The red dots along the border moved me to act. I was interested and doing research but I was a student at Hunter College for three and a half years and I couldn’t travel to the border.

My work deals with the effect of architecture and specifically border architecture. Especially coming from the Israel border the architecture there is very prominent, it’s very developed. Society lives with the borders in a way that it has evolved rapidly and it’s deeply ingrained, from a soldier standing at a checkpoint to the towers and concrete to sensors. A whole mask that makes us forget what’s beyond the pale.

I hope that the American border won’t become to be like the Israeli border.

EMD: What did you see while in Arizona?

ZH: I had this proposal to go to Arizona and record sound at the border. I devoted three months to applying for grants because I realized that’s what I needed to do.

And I think the same week I got funding from The Café Royal Cultural Foundation I booked a flight ticket to Phoenix, Arizona and scheduled to volunteer with the Humane Borders Organization.

I learned a lot joining the water runs once a week with the Humane Borders Organization and their weekly meetings. I conducted interviews with the members. Their primary mission is ‘to save desperate people from a horrible death by dehydration and exposure and to create a just and humane environment in the borderlands’.

I’ve learned to keep refreshing my memory to remember that there is no such thing as an illegal human and humanitarian aid is never a crime. I learned about how easy it is to help.

I also traveled to Tohono O’odham Reservation. I contacted the museum only with the purpose to learn. I thought a lot about the wild plant life and the desert. On how nature protects itself from predators and the absence of western society.

I had heard about how important the land is, how the Indigenous people protect it but it was only when I went there that I realized it. I don’t need to know more than that after visiting. It’s very clear to me that you can’t have a border there and we have to respect that.

That respect is really for us, as people that live on earth. They’re kind of lost values we don’t express anymore, which is very sad.

The Sonoran desert is beautiful and yet if you try to cross it’s deadly.

EMD: What was your volunteering experience like?

ZH: It was about learning more on the humanitarian crisis happening at the Arizona border with Mexico, the flow of asylum seekers from Central America, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala that flee due to crime, violence and political corruption. People that leave their home with their families and kids to find a better place and not knowing where they’re heading to. They don’t know that they’re heading into a death trap.

I volunteered at Casa Alitas Program – Aid for Migrant Families, they receive families from the detention center. Being witness to the details. For example, many families came in with shoes without shoelaces. This is due to a prison routine to prevent people from hurting themselves, Asylum seekers are not criminals, they haven’t committed any crime and still go through this. Worse still is that if they’re released back to Mexico without shoelaces they are easily singled out by gang members, putting them back in the same danger they are looking to escape.

EMD: Do you have another trip planned?

Yes, I plan to volunteer again this summer and continue developing this project. Worth mentioning the exhibit has a commitment that a percentage from any proceeds will be donated to the Casa Alitas Program – Aid for Migrant Families.