Curated by Juliana Steiner, “Holes in Maps” looks at global political currents via geography–with a rather jaundiced eye. Seven artists are participating in the show: Aila Farid, Matej Knesevic, Adriane Martinez, Reynier Leyva Novo, Juan Obando, Regina Parra, and Sanne Vaassen. Central to the organization of the exhibition is the conceit of the rhizome–a root-like stem extending horizontally beneath the ground, from which roots push upward. The image presupposes a democratically equal growth pattern, something intimated in this very interesting show’s critique of vertically hierarchical systems. Maps with holes in them serve to contradict our need for determining space and topography in ways that enable us to control the landscape. More important, in this show the references have to do with the power behind the determination of national boundaries and the way in which people are influenced–or damaged–by changes in such boundaries.

The contiguous contours dividing one country from the next in map systems are not only a practical device; they also serve as a theoretical metaphor underscoring our need for containment and clearly divisions of space. As such, they play into our current mindset in which nations are defined as separate entities, whose lines of demarcation evidence the ways in which geography can strengthen a country’s geo-political position. The works, then, in “Holes in Maps” reminds us that art can be used to explicate, advance, or deny the impulse of being confined through borders, despite the fact that so much of the world has seemingly been permanently measured and arranged, primarily for political and economic reasons.

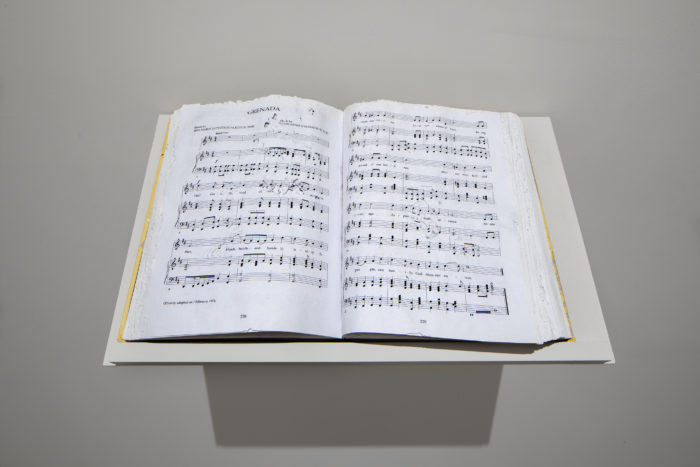

Vaassen’s piece consists of an anthology of anthems, words and scores, that was fed to snails, who ate their way through the paper. The decimated text and music can be seen as a reading for the way national identities, via cultural heritage, are now distorted, even mutilated. Interestingly, the snails are not a cultural but a natural phenomenon; their destruction of the manuscript is entirely random. So we see how the damaged cultural materials cannot be resurrected into an expression of holistic report, representing the variousness of national expression. Instead, the damage is permanent, as it seems to be culturally throughout the world. Knesivic’s Bittersweet Euro (2015), a large facsimile of the coin created by hanging circular cookies, open in the middle, from nails on the wall, reduces Europe’s basic currency to a commercial bakery good. This work addresses the economic reality people in Europe face, alluding to the difficulties resulting from a supposedly unified currency.

Colombian artist Martinez’s Tutti Frutti Market (2018), a wooden fruit stand filled with plastic fruits covered with stickers in a plastic crate, question the economy and the produce of globalism. Installed next to the door of the gallery, the fruit stand looks entirely out of place, while the plastic fruits look so artificial as to be absurd. The stickers found in the fruit remind us of visas and strict passport control. Brazilian artist Regina Para’s Metegol (2014) is a hand-painted foosball table, divided by a column in the back of the gallery space. Football, called soccer in the United States, is our world sport, while the game is found in bars all over the world. But here the context is more specific. This work was the property of the impoverished Bolivian community in Sao Paulo, who gather on the weekends to play the game. It is a way of creating community within a group given neither attention nor respect.

The three videos on view in small televisions, address the Iraqi invasion in Kuwait known as the Gulf War. Farid, originally from Kuwait but now in living and working in Puerto Rico, put together close to four hours of newscasters collected by her grandmother. It is a demonstration of the instantaneous world culture that is found in news shown all over the world. The decision of having three monitors alludes to “The Gulf War did not take place”, three short essays by the French sociologist Jean Baudrillaud, which considers the conflict in light of the reception of the general public. Another piece, a telescope, a work by Cuban artist Novo placed on a two-step platform at the back of the gallery, is called Eternamente te Esperaré (2015). The piece is based on the thousands of Cubans who leave their country and sail in real danger, attempting to arrive in Florida, many times dying in this pursuit. The telescope zeroes in on a video of a makeshift boat with the phrase, in Spanish, “I’ll forever wait for you.” Who is waiting for whom? The reference to the uncertainty of the immigrants’ lives gives the work unusual gravitas.

Museum Mixtapes (2014), by Colombian artist Obando, is a 22-minute video that combines the performances of different rappers from the southeast of the United States freestyling inside art in museums close to where they lived. Their spontaneous narratives, at once garish (even vulgar) but moving, pose an alternative view to the “high” culture on exhibit at the museum. Generally speaking, the works in “Holes in Maps” attempt a radical transformation of culture that seeks to redress the psychic anonymity of the poor, whose culture is ignored or, worse, deliberately damaged by the ubiquity of art from a higher class.

All in all, the show is a telling, highly accurate presentation of the way a global, capital-oriented economy is slowly but surely shutting down the possibility of economic, cultural, and social freedom. There is no overt violence taking place, but technology has brought about a sameness of experience, when doing so is greatly damaging to art. Much art today is talking about this situation, but it looks more and more like we are being forced to accept a living in which cultural difference is negligible. The sameness is deadening, even if US affluence remains a calling card for those who want to live a more humane life. Artists can do little but comment on this kind of thinking, and much of work we see, as happens in this show, illustrates the marginality of the poor, whose lives are reduced to a silent existence on the edge of metropolises. This show illustrates this very well. Still, it can be suggested that we need to find ways of making art that emphasizes culture, and even something so ethereal as beauty, as well as social mores. Curator Steiner has put together a telling interpretation that exists in support of people whose lives are economically and socially anonymous. Given the ubiquity of our financial restraint, this may all we can do.

HOLES IN MAPS

Curated by Juliana Steiner

Dec 1, 2018 – Feb 17, 2018

Photographs provided by 601 Artspace/ Marie Noele Guex.