In Technics and Civilization (1934), Lewis Mumford famously wrote: “Until we have absorbed the lessons of objectivity, impersonality, neutrality, the lessons of the mechanical realm, we cannot go further in our development toward the more richly organic, the more profoundly human.” Refusing to see machines merely through the lens of productivity optimization, Mumford suggests that technologies are symptomatic of the crises inherent within the human condition. At SHRINE New York, Craig Kucia’s solo show, machines to solve unsolvable problems, contemplates a similar set of issues. Can an automated feedback loop make hard feelings more navigable? To what degree are machines funny, emotional, pedagogical, or useless?

The show’s storytelling is notably strong. These machine paintings all possess a certain narrative or autobiographical quality, responding to questions such as “Why can’t my dog live forever? Why am I not more empathetic? How can I touch the moon?” In a machine for aging (dogs), machine hands become instruments of care, as they caress, pat, and guide the artist’s dog, Neel, “who had suffered from dementia the last few years of her life.” a machine for self-perception situates the artist’s palette as an anthropomorphic protagonist within the genre of self-portraiture, reflecting upon how artists identify with and live through their art. It also seems to explore the sources of artistic inspiration, self-critique, and self-compassion. Personally, the chaotic array of plants and drawings in a machine for social anxiety really hits home, as it perfectly encapsulates how I’d sit on a pile of books and dirty laundry in an avoidant mood when multiple deadlines are imminent. Processing anything from existential questions to innocent curiosity, these machines almost deny the fundamental logic of mechanics, i.e. calculation, as they address problems that cannot be reduced to precise science—the encounters and dreams that are fundamentally human.

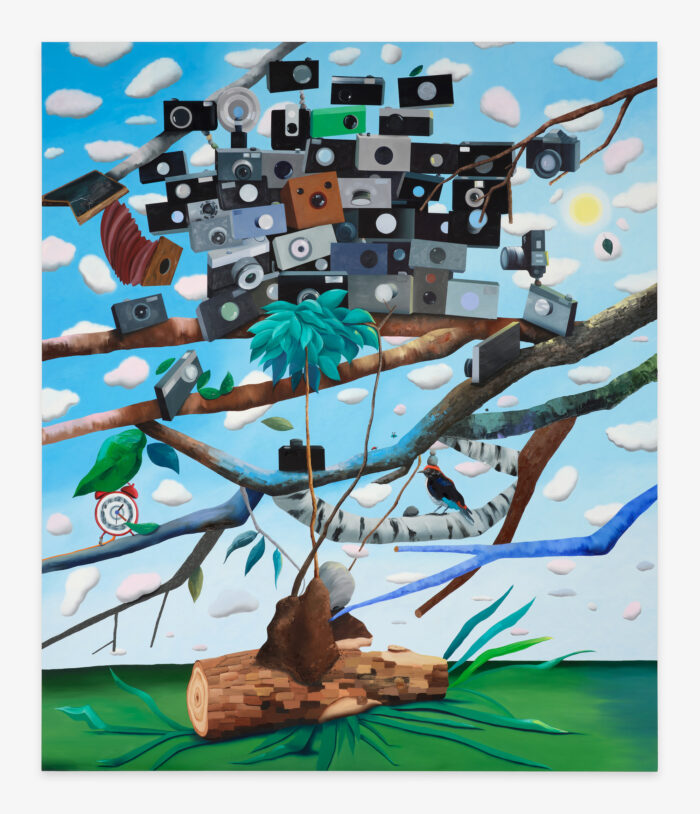

Kucia’s machines are more playful than stoic. His vibrant, Hockney-esque color palette is catchy and fresh. With cleanly defined contour lines, slippery spatial relations, and a distinctive fondness for alternative framing, these oil paintings situate a seemingly random group of animals and inanimate objects within an interconnected system that defies gravity, temporality, and geographic specificity.

Humor abounds—just intentionally downplayed. For instance, the window in a machine for empathy opens up to some bacon-like rain clouds that hover over a grassland. We’d think we are looking at the interior of a country cabin. But right below the window, a pet door in the wall frames the view of a clear sky, rendering the room virtually afloat. All of a sudden, we might as well be looking at a celestial temple like The School of Athens. In a machine for indecision, a sunflower is smashed against a galaxy poster, its pollen spilling out from the disc-like stardust onto the picture within a picture. Next to the sunflower, a cracked egg echoes the shape of the ringed Saturn in the poster—notice how the planet’s ring is paler compared to its yolk-like globe? The egg motif, once again, is echoed by the representation of another celestial body—the sun—in a machine for inattentional blindness. Through repetition and parallelism, a strategic visual seduction takes the stage, hinging on ideas of entertainment and play.

The dynamism of these paintings induces a close observation of how planar surfaces and sticker-like objects interact with one another. The recurring techniques of framing and superimposition have strong art historical implications: from René Magritte’s window paintings to Duchamp’s Tu m’ (1918) to Ellsworth Kelly’s Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris (1949). Despite this acute awareness of art historical references, the artist refuses to “make work inspired by an aesthetic” but instead seeks opportunities for re-contextualization. Therefore, Rube Goldberg machines are juxtaposed with conjunctural oddities, rendering this series of paintings a theater of problem-solving—a mechanism of thinking, an attempted action, rather than a solution.

In Giedion’s Mechanization Takes Command, machines are seen as an outcome of humans’ “rationalistic view of the world,” and questions arise as to whether mechanistic trajectories are “in any way connected with the emotional impact of the signs that appear time and again in our contemporary art.” The exhibition machines to solve unsolvable problems seems to be responding to this question. At the intersection of automation, vulnerabilities, anthropomorphism, and humor, Kucia’s painted machines draw the viewer into a haven of introspection and meditative close-looking.

Craig Kucia: machines to solve unsolvable problems is on view at SHRINE, New York, until December 9th, 2023.

INCREDIBLE SHOW that seems to be under the radar right now in NY. Never heard of the artist before and it’s some of the more interesting work I’ve seen in anwhile and am surprised he is not more well known.