At Rachel Uffner Gallery, the two-person show A dreaming hand, wounded by thorns presents the work of Andrew Woolbright and Gitte Maria Möller. United by a shared interest in digital myth-making and art historical references, the two artists complicate notions of selfhood, memory (digital and neurological alike), and simulacra by gleaning images from a multidimensional past.

Among the most eye-catching works was Woolbright’s large-scale painting, Haruspexing the Virtual Sublime (2021-23). Using collage techniques and layered iconographies, the artist includes a conglomeration of objects sourced from personal and intellectual encounters: the hand of Sabazius, classicizing human forms, and sexual wellness products. As part of the frame, small plexiglass panels reflect or duplicate the sources of certain pictorial references. According to Woolbright during a talk at The Brooklyn Rail, as he continuously worked on the same piece over the course of three years, the artist who initiated the artwork was no longer the same as the person who finished it. In this confusion of psychedelic colors and forms, he even introduced acrylic paint peels as part of this collage, evoking the language of materiality, assemblage, and the readymade. So first and foremost, it is a painting of fossilized change.

Nevertheless, cultural history savoir faire does not necessarily equate to antiquarianism. In fact, like Woolbright’s other works, this painting is reminiscent of how Jean Baudrillard’s simulacra may cast an impression on the “narcoticized and mesmerized media-saturated consciousness”—a symptom of nowness. The confounding combination of brand names, consumer products, and relics solicits not a reading but a diagnosis: information overload. In A Higher Court of Vision (2023) for instance, it is likely to be more frustrating than fruitful if one tries to interpret how the Wassily chair relates to the cheeky wordplay on “Polari(s).” One almost wants to resort to ChatGPT for a reverse outline session to understand how everything fits in one painting. As far as the human viewer is concerned, it feels somewhat debilitating to stand in front of a painting for 20 minutes, only to find another overlooked icon amid expressive paint strokes at minute 21. In other words, the artist perfectly captures how the sheer volume of information experienced by the contemporary spectator is translated into a sensibility of overwhelm. Taking a step back, the source of this feeling, ironically, is the same as the main site of contention addressed by this show: digital interface, media, and the mental habit that seeks to understand the present in juxtaposition with the past.

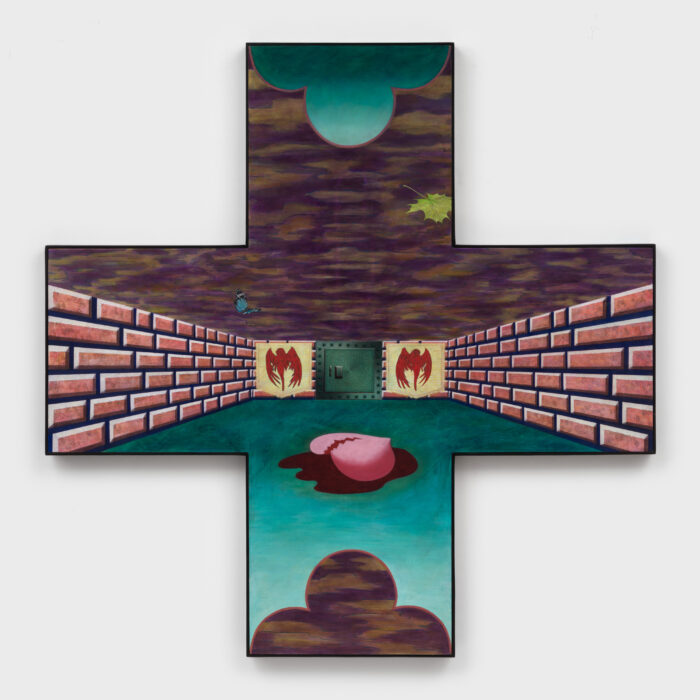

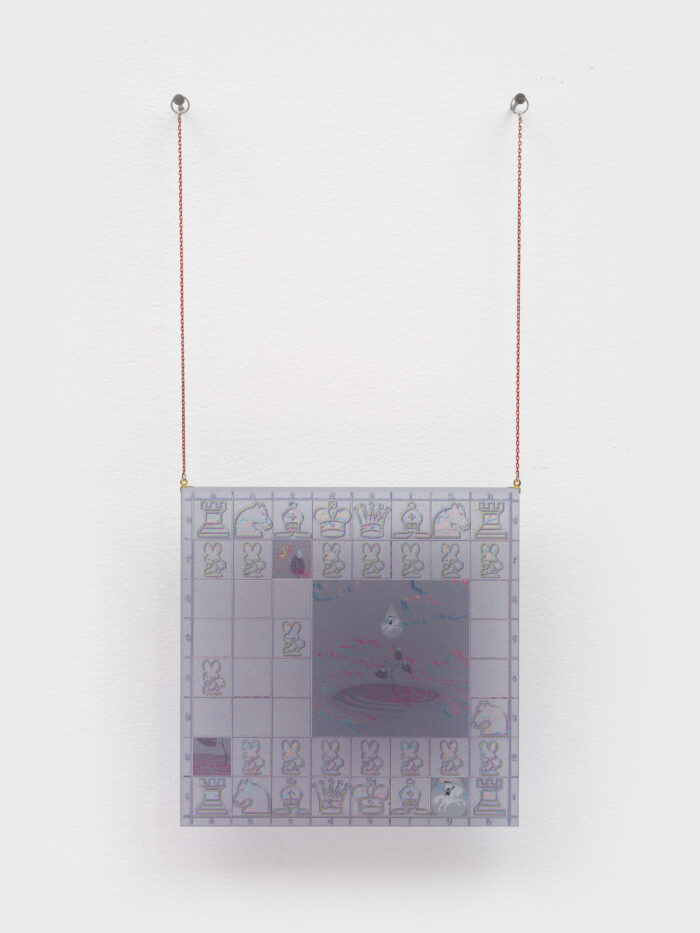

Stylistically, Möller and Woolbright are quite different. Where Woolbright is open and gestural, Möller is calculated and clean. Where Woolbright uses an all-over composition, Möller deploys symmetry and perspectival lines. With delicacy, precision, and elegance, Möller’s paintings and charms form viewing windows onto a landscape that intertwines the digital with the mythological. She makes fictional architecture out of polygon meshes, axonometric perspectives, decorative patterns, and layered “opalescent” colors. The press release also elucidates how she references the aesthetics of early video games.

In i-D’s recent interview with the artist, Paige Silveria astutely described Möller’s works as reflecting “the visual impact of a secluded Protestant upbringing in Cape Town, as well as the growing sway of popular culture.” This amalgamation of influences generates an internal heterogeneity that complicates the viewing experience. Take Pushy Passion (2018-23) for instance. One can say that we are looking at a cross-shaped panel with brick walls, a bleeding heart, two banners, clover-shaped cutouts, etc.; but as my vision bumped from a butterfly to a falling leaf, I was left with a sensation similar to scrolling through Instagram: different categories of recommended videos flash for seconds before going away, but the fragmented pieces of information leave indeterminate the possibility of constructing coherent meanings. In front of Möller’s paintings, Knights of the Round Table and Ninja turtle cassette games come to mind at the same time. Signs that used to hinge on particular contexts and meanings have now become anachronistic constituents of the postmodern identity. In this way, these works shift their focus away from storytelling, but instead present a setting or environment where signs are infinitely approaching the asymptote of meaning-making.

Questions of how art exhibitions mediate display and simulation also come into play. Some say that the loom is the first computer. I am wondering if the painting is the first tablet interface. If we could project video games on a TV monitor, why do we reproduce those visions in art? Similarly, in the top left corner of Haruspexing the Virtual Sublime and The Coral Fisher are two USB drives containing the visual inspirations behind the works. If we could store and communicate information via a USB drive, why do we blow these images up on a large canvas and then again on plexiglass attachments? When we are living in a chamber predicated on the display of information, are art forms obligated to reflect this reality or irreality?

A dreaming hand, wounded by thorns perfectly reverberates the visceral sensation of navigating digital noise, proposing a condition where visual information is overabundant and relentlessly reinvented. In a room of superimposition and becoming, Jean Baudrillard is once again proven prophetic.

A dreaming hand, wounded by thorns is on view at Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York, until January 6th, 2024.