Philip Guston, 1969 – 1979 at Hauser & Wirth, NYC (22nd Street)

September 9 – October 30, 2021

Images and © courtesy of The Estate of Philip Guston and Hauser & Wirth.

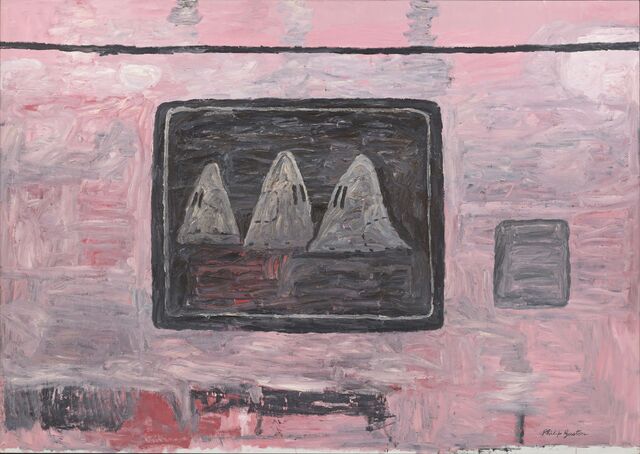

Philip Guston’s place in American art history s fully established, and this show of his late work, from 1969 to 1979, makes it clear why he has so much to say to us now. He began as a figurative, often political artist, painting the Klu Klux Klan figures that prompted the controversial delay of his show a while ago. But then he moved into abstract impressionism, in which small marks were massed onto a mostly light background. This work was thoroughly approved of, but in the late Sixties, when Guston moved into his coarse cartoon-like figurative style, the change was met with shock and harsh judgment. In this relatively small show, about a dozen paintings, we don’t come across the well-known political cartoons of figures like Nixon; instead, we see allegorical works that reflect a nearly apocalyptic reversal of his delicate abstractions in favor of troubled, troubling, rawly rendered images of the tops of garbages cans, pictures of the artist in bed, and re-viewings of figures in the Klu Klux Klan clothing–the imagery that people became so concerned about.

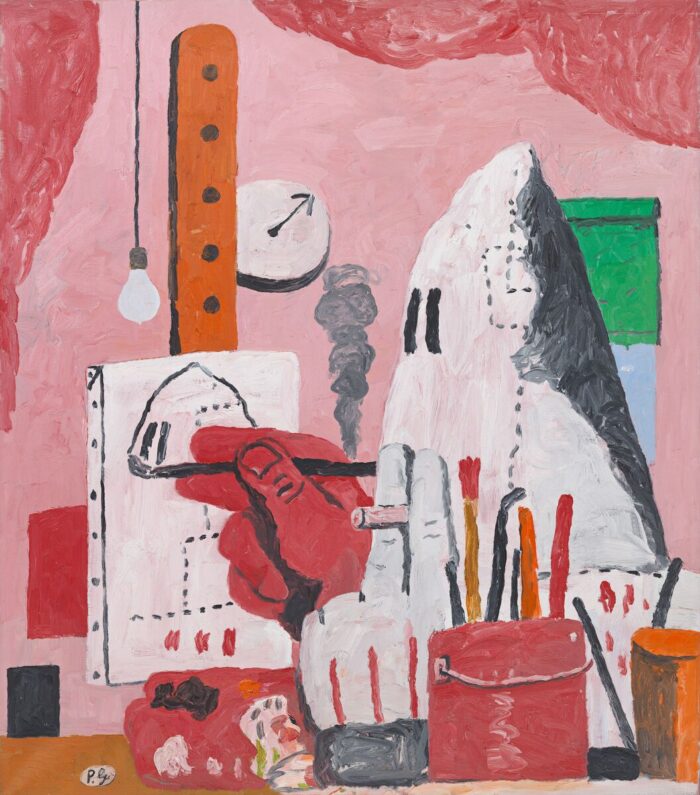

In The Studio (1969), Guston paints someone, presumably himself, in full Klu Klux Klan regalia, smoking a cigarette, its gray smoke issuing upward, as he works on a likeness of himself in the same provocative clothing. The back wall is pink with red curtains, while the foreground is taken up with the paraphernalia of his vocation: a palette, a can filled with brushes. In some ways, this is a deeply traditional work of art: a self-portrait indicating the artist in the middle of the work. But the uniform Guston is wearing politicizes the image in a contemporary fashion, given a context as he refers back to work done decades before in political anger. Today, we may be slightly bemused by the composition, whose brutal honesty, along with its slightly obscure imagery, actually speaks to a directness felt necessary by many in today’s art world.

Another politicized work, called Back View II (1978), shows a mass of mostly garbage can lids, with maybe a few shoe soles evident. It looks like the grouping of police shields that might be advancing toward demonstrators. We can see two hands and at the top of the work plus a head of black hair. This is an ungainly attempt, deliberately so, at proposing an image that is allegorical without specifying its specific meaning. Most of the paintings work like this: their import is suggestive without spelling out details.

Tears (1977) offers us a set of huge eyes with black pupils and very large eyelashes. The tears, one to each eye, seem to be falling onto a dark coverlet. A white pillow holds up the back of the painting. What is the man, again we assume it is Guston himself, weeping about? We simply don’t know, although we accept the blunt pathos of the picture. One assumes this is a self-portrait of the painter in a dark moment–a moment we all have experienced at some time. The facture of the work could not be more coarse, but by painting in this way, Guston emphasizes the emotion involved. In the long run, it becomes clear that this body of work takes private feeling and renders its public by presenting the image as unrefined, open to a brutalized reading, both public and private. Today, in a time of intense political feeling, made personal by the experience of young artists, it is feasible to see Guston as a harbinger of a style that merges personal feelings with social anger. He is an artist whose sense of doom comes through in this body of work, perhaps because of increasing age but more likely because of the violence of the time. As a result, these paintings develop a resonance with our sharply voiced concerns at present, speaking to genuinely contemporary issues.

Jonathan Goodman