Mumbai-based artist Akshita Gandhi’s first solo show in the UK is presented as a “love letter” to her home, reflecting on seventy-five years of Indian independence from British rule. In her work, the city streets of Mumbai and Udaipur are shown as electric, fluctuating scenes, with skyscrapers pasted to the sides of tenement blocks. As architectural eras fade into each other, Gandhi’s Pincode series of altered photos capture the chawls (tightly squeezed housing blocks from the 1700s) alongside British imperialist buildings and modern high-rises. Sections of the highly saturated photos are repeated like a pattern, with glimpses of people throughout.

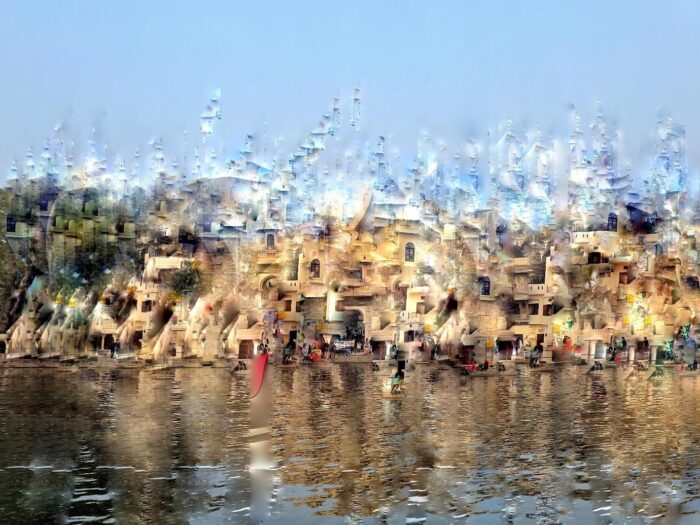

The result feels like a hot memory, with shimmering waves of distortion hovering above the roads. Lake Pichola, Bhram exemplifies this phenomenon. Heatwaves rise above a murky body of water until they appear as a new skyline cut from majestic doorways and windows. The mirage floats above the bodies gathered at street level with doors closing and windows locking as the illusion soars upwards and out of view.

A love letter to my home is presented at The Nehru Centre, the cultural hub set up in the 1990s to facilitate and deepen cultural dialogue between India and the UK through art. The building itself sits on the grand South Audley Street in Mayfair that previously housed the London Bachelor’s Club. The club was said to “admit no foreigners” and disqualify men once they married. These 1930s bachelors who were hostile to foreigners were almost certainly intertwined with the ruling classes that sat in comfortable seats in British India. In bricks and mortar, and names on walls, History has a way of making its presence known. Nearly a century later, these storied walls provide another layer of collage to Gandhi’s Pincode works. The white gloss paint catches the light, distorting the images further and reflecting the viewer back to themselves as they observe.

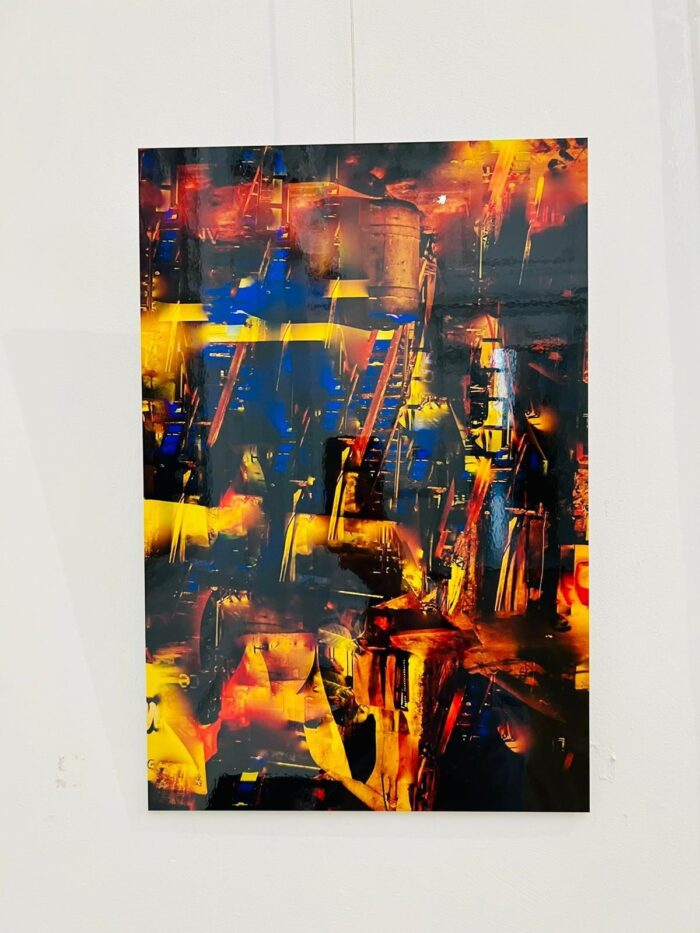

Gandhi’s series focuses on neighborhoods marked for demolition and the speed at which this occurs. In Mumbai, the “city of dreams,” there is a constant pull of redevelopment and upward mobility. It is impossible to ever remove the past fully, to raze India’s imperial history to the ground. Instead, the architecture of the city piles on top of itself in a decoupage of history. This is most evident in Gandhi’s images of Udaipur. Her lens shuns the famous Rajput palaces of tourist postcards in favor of the small houses that sit atop businesses in the bustling centre. This version of the city is a living, breathing document of how people interact with the streets and shops of memory. Layers of recollection repeat in the work Elphinstone Building — a swathe of Himalayan satin hung across the room, studded with sequins and hand embroidery — and in the Fluids series, in which splashes and scratches of paint sprawl across landmarks like the Baan Ganga Temple. Where her digital Pincode works capture the gentle buzz of night, Fluids is a vibrant dance, an unpredictable altercation with a photograph. Paint and resin roll across the canvas, obscuring historical insurance buildings and causeways alike.

On 18 July 1947, royal assent was given for Indian independence, officially granting self-government to what had been known as British India and the princely states for almost 90 years. New borders were drawn through what we now know as Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, splitting communities and cities across maps. The inclination to name and demarcate boundaries gratifies the colonial urge to conquer through categorization. Hence imperial “British India” becomes an autonomous dominion, and the decision is declared the Indian Independence Act. The reality is always murkier, as one ruler replaces another: independence from the Raj brought with it displacement and a new form of unrest as historical tensions seeped through from the previous era.

The exhibition features drawings, paintings, a video work, and a textile piece curated as Gandhi’s personal and physical Love Letter to her home country, transported to the grey skies of London. Among these works of explosive color hangs Ummeed (Hope), an initially unassuming tarpaulin sculpture that Gandhi took across Mumbai. Bearing the marks of the city, torn and weathered by the movement of rebuilding, it is draped across the clean bright white of the Nehru Centre walls. It stands as a monument to the building sites and the outdoors, to precarious entrances and exits, the ways history begins and seeps into itself.

Akshita Ghandhi: A love letter to my home is presented by Gabriel Fine Arts and on view at The Nehru Centre, London W1K 1HF, 23-27 May, 2022. It can also be viewed on Artsy.