Sprüth Magers, Grafton St.

London

Fri 17 Jan 2020 to Sun 19 Apr 2020

Photography: Stephen White

PR: At the centre of this exhibition is the large-format sculptural installation The Raft. The work is made entirely of polyurethane; a material Fischli Weiss first began using for their sculptures in the early 1980s. Polyurethane was originally used mostly in film productions, where it was employed as a component in props and scenery construction. This choice of material situates the installation in the realm of the workshop and labour, a subject the artists explored from the outset of their work together.

The Raft (1982/83) hasn’t always had its present form. Its predecessor, Mad Max (1982), made shortly after the film of the same name was released in 1981, consisted of a number of polyurethane parts mimicking civilisational detritus and various types of rubbish. A gloomy and mundane collection of objects, the original work was realised in a time where science fiction cinema conjured a world of destruction that could also be felt in the real world, thanks to the tense social climate of the Cold War, the threat of nuclear power, and environmental problems. However, it was during the exhibition ‘Die Sonne bricht sich in den oberen Fenstern’ (‘Sunlight breaks in the upper windows’), organised by Martin Kippenberger in Cologne in 1982, that The Raft took on its current title and present, ultimate form: the installation, which is carved entirely out of polyurethane, consists of a platform of loosely assembled planks upon which a number of mostly banal objects including canisters, barrels, and wooden crates, are piled. Crocodiles and hippos circle around.

The new title of The Raft shifted the contextualisation of the work: its gloomy symbolism transforming into a more generalised picture of hope and destruction – a place of refuge over menacing waters (though the encroaching wild animals continue to pose a danger). In contrast to Théodore Géricault’s painting The Raft of the Medusa (1819), which might be considered a compositional model for the piece here, it isn’t human lives that the raft appears to be saving, but all sorts of ordinary, commonplace things. Few of the accumulated objects would be helpful in saving passengers from attack, nor could the cannon, a worn-out tyre or an old furnace be described as objects worth salvaging on their solitary journey through the waters. Only the sow with her piglets recalls Noah’s Ark and its positive message. This merging of hopeful and apocalyptic imagery evokes the context of the time in which the work was created, whilst simultaneously lending Raft a very contemporary relevance. Then, as now, the materialism symbolised here described an odyssey through the world.

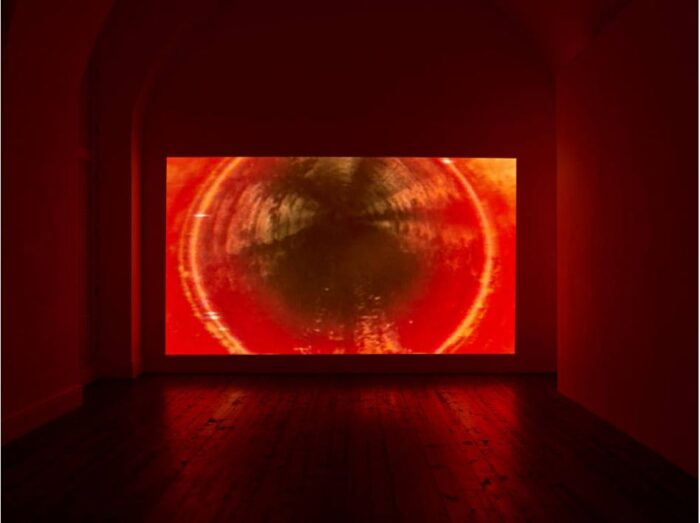

On view in the gallery’s lower level is Kanalvideo (1992), a soundless, 60-minute video of footage from a camera advancing through an empty sewer pipe. Though winding its way through the most trivial of our infrastructures, the route through which waste is disposed, the multi-coloured shots invoke something akin to a hallucinogenic state. The most humdrum aspects of everyday life are transformed into an abstract, contemplative snapshot – a stream of ever-new, mandala-like images with a maelstrom pull. Kanalvideo develops this balancing act, between unpretentious simplicity and complex effect, into a poetics of the ordinary.

This theme of overstatement of the everyday in all its facets takes bizarre, fantastic shape in the pair’s Fotografias (2005), a series of photographs shown as the third work in the exhibition. Exhibited in long rows on the walls and on tables, the 10x15cm black-and-white photographs speak to the oversaturated image culture of our time. In the spirit of Fischli Weiss’ canonical work Visible World (1987–2000) and its depiction of the commonplace and omnipresent, Fotografias (2005) draws on the world of trash culture, quoting the aesthetics of amusement parks and their promotional signage or decorated carousels. The photographs obscure the often stridently colourful, large-format iconography from these amusement industry aesthetics; they employ close-cropped compositions translated into small-format, black-and-white prints in an alienating step that causes once exuberant, wild pictures – images that normally beckon towards enjoying a moment of imaginative fancy – to become mysteriously impenetrable.

Peter Fischli (*1952 in Zürich, Switzerland) and David Weiss (*1946 in Zürich, Switzerland, died 2012 in Zürich) began working together in the mid-1970s, continuing their collaborative practice until Weiss’ death. Together they have exhibited at many international biennials, including the Venice Biennale (2013, 2003, 1988), the Venice Architecture Biennale (2012) and the Gwangju Biennale, South Korea (2010), while retrospectives have been held at Tate Modern, London (2006), Kunsthaus Zürich (2007), Deichtorhallen Hamburg (2008) and recently at Salomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York and Museo Jumex, Mexico City, MEX (2016). In 2003, they were awarded the Golden Lion at the 50th Venice Biennale for Fragenprojektion (‘”Questions,” 1981–2002). The artists showed at documenta X, 1997, and their film Der Lauf der Dinge (“The Way Things Go”, 1987) was shown at documenta VIII, 1987. In recent years, their works have been also presented in solo exhibitions at the Glenstone Collection Potomac (2012), at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan (2010) and at Sammlung Goetz, Munich (2010) as well as in numerous group exhibitions.