13 Mar 2021 to 15 May 2021

All Images courtesy of Semiose

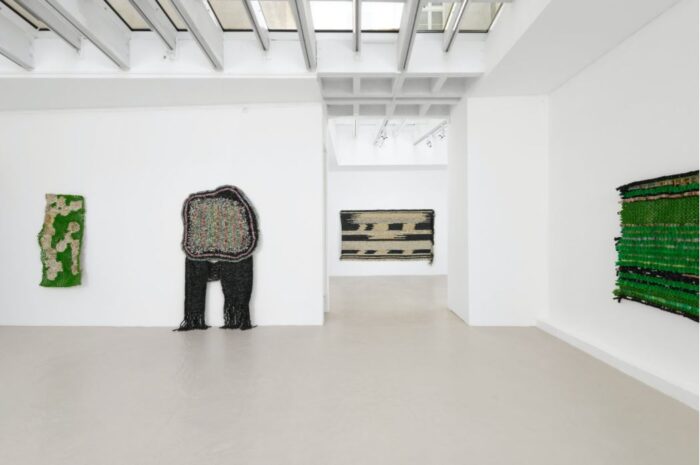

For his first Parisian solo show, Moffat Takadiwa (b. 1983 in Karoi, Zimbabwe) is presenting a number of hitherto unseen sculptural pieces at Semiose gallery. One of the most acclaimed artists on the emerging African art scene, he has enjoyed exhibitions in both galleries and institutions from London to Singapore via Johannesburg. Moffat Takadiwa is a truly global artist. His now well-recognized practice of sublimating the waste products of our capitalist economic system (hyper-globalized in its own right), has shown that it is capable of creating a buzz on almost every continent and within many cultural ecosystems.

Through the recycling of astronomical quantities of computer keyboard keys, various nozzles and caps from aerosol cans and soda bottles, or toothbrushes and toothpaste tubes, each of Takadiwa’s sculptures is intended as a sublimating act of resistance against the spread of local and global waste. Although they principally refer to the massive dumping grounds that cripple local industries in Zimbabwe, the sculptures are also evocative of Africa’s more general resilience faced with western liberal economies—and their waste.

Far from the “solidarity” and “fair trade” economics, so much in vogue in today’s marketing (in other words that have been appropriated by capitalism), the garbage dumps that Takadiwa witnessed in the early stages of his artistic career, in the mid 2000s, have come to represent as much a curse as a blessing (like oil, “black gold” on one hand and the source of great conflict on the other). In this instance, beyond Takadiwa and his sculpture, these tainted materials constitute a recyclable artistic commodity for a whole generation of local artists. Imagine huge dumping grounds seen from the sky—like the spectator’s gaze plunging into the chromatic labyrinths and whirlpools of Takadiwa’s “wall-carpets”—reveal oceans of plastic, metal and fiber waste. One can make out the wandering shadows of gatherer/collectors, some seeking to resell these ersatz raw materials for profit, crossing the paths of artists and their acolytes, who collect the booty for recycling and use in their own projects. In short, a vision of a crumbling economy trying to rebuild itself on the site of its own collapse. (1)

We are obliged to adopt a dual macro and microeconomic perspective, since this invasion of waste (this accursed share of the capitalist economy) is played out as much at the level of the raw materials managed by large industrial groups, principally from the West (although Chinese involvement is increasing rapidly), as at the level of the informal economy of the market stalls of Mbare (Zimbabwe), which are undoubtedly the most well supplied and bustling of the whole country, in terms of exchange of goods. A township located in the southern outskirts of the capital Harare, Mbare is an archetypal peripheral or suburban zone, far from the rural Tengwe region and its numerous farms where Takadiwa grew up. It is an archipelago of market stalls and street vendors that one can somehow imagine as the lung of the Sisyphean labor that is condensed in Takadiwa’s sculptures. The topographical landscapes of his more recent works however, refer more directly to the tobacco fields of his childhood that the artist continues to roam. These tobacco fields constitute a major source of wealth for the Zimbabwean economy but are equally seen as an ecological catastrophe as they have led to the removal of trees vital to the local ecosystem.

The suburban (and rural) dimension of Takadiwa’s aesthetics does not only have a sociological focus. While Takadiwa is clearly a suburban artist shaped within a hybrid economy that is both rural and urban, the suburban dimension also manifests itself in the allegorical power of the works themselves: these fabrics made of plastic and junk reveal hubs of activity and road intersections through sets of spirals, mosaics and other criss-cross patterns, as if displayed on a (sub) urban map—like a vast mise en abyme, on the edge of entropy, between the oeuvre and the ecosystem that generated it. The shapes and colors of these sculptures, apparently predetermined yet random in nature, like algorithms, seem to be made up of intertwining networks, like pockets of informal economy. The fishing net used in these works to anchor the diverse bits of rubbish together, serves as a metaphor of the suburban and rural experiences which far from any smooth, free-flowing and ordered environments, is played out in striated, chaotic and saturated spaces, full of twists and turns. (2) So we come back to Mbare and its multiple ramifications, the agricultural produce market (Mbare Musika), the cheap clothing market (Mupedza Nhamo), the metal objects and container market (Magaba)—so precious for Takadiwa’s sculptures—as well as the market for “traditional” works of art (The Curio Market). Takadiwa’s suburban, post-industrial fabrics are like great barges or giant conches, that collect and sublimate these accursed vestiges, the residues of capitalism, which very early on in the political stance taken by the artist were identified as colonial residues.

This non-recyclable “shameful” share left as an inheritance or still dumped in the lands of the most disadvantaged by their former colonial rulers, puts Africa in danger. It creates a scorched earth of industrial waste and decaying merchandise. And it is this that Takadiwa subverts with a touch of grace and all the radicality it deserves.

Takadiwa is moving increasingly towards a quasi-industrial process of collection and production, but still retains a more informal aspect to his work. He has gathered together six or seven studio assistants to assemble his pieces, and above all around thirty collaborators, who scour the various public dumps, collecting the commodities so highly prized by the artist.

Given all the workers, transporters, buyers and sellers the town attracts, Mbare has become a melting pot for the local population, often from remote rural areas, and people from Mozambique, Malawi and Zambia, territories to which Zimbabwe is linked through its late nineteenth century colonial history. Its leader at the time was Cecil Rhodes, the owner of vast mining interests and head of the British South Africa Company, and who embodied the planned expansion from South African soil into present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe, which when annexed in 1895 came to constitute “Southern Rhodesia” (named after the aforementioned Cecil Rhodes). In 2017, Takadiwa produced one of his most important works, probably the most “political” of all his oeuvres, which he named The Falling of Rhodes/ia. With its monstrous and grotesque features, the wall sculpture mimics the statue of Cecil Rhodes, a monument to the British colonization of Southern Africa. Through this act of historical subversion, which constituted a fundamental turning point in his own poetic-political journey, Takadiwa linked his destiny with that of the militant movement Rhodes Must Fall. (3)

The town of Mbare, through its cultivation of strong connections with other ex-colonial territories, represents much more than a frenetic urban and mercantile allegory: the localized violence of a globalization imposed without regulation and at the lowest cost, exploiting the populations through which it spreads. Beyond their obvious aesthetic qualities, Takadiwa’s works reveal the profound historical and economic issues hidden behind the noise and chaos of Mbare’s labyrinthine and polycentric marketplaces, of which they are a subtle metaphor. The town’s (neo)colonial subconscious resurfaces all the more violently, as the decolonization of Zimbabwe was a painful process achieved through a bloody struggle for independence (especially from the 1960s onwards) and in a very tardive manner. Zimbabwe was almost the last African country to gain independence (April 8, 1980). Moreover the smell of smoldering ashes is never far away, even for Takadiwa’s generation born in post-independence Zimbabwe or as is often said “born free.” It is undoubtedly up to them, in the present day, to take charge of this slice of memory, of this subaltern subjectivity, largely maintained in silence, far from school textbooks and official monuments, etc.

This post-colonial subjectivity is inextricably entwined with the English language, which Takadiwa enjoys mistreating in his vortices of keyboard keys (QWERTY as a battlefield), with Zimbabwe’s love / hate relationship with the Commonwealth and more recently with the current extension of the “silk road,” increasingly promoted by China, whose investments in Africa are sometimes toxic and at others remedial.

Subaltern: the rich vein of memory in Takadiwa’s sculptures is even more complex as it is also linked to the violent events of June 2005 when Mbare’s trading area and its multiple markets found themselves the target of a vast operation of destruction and eviction carried out by the authoritarian Mugabe regime. Using the pretext of dismantling the black market, Mugabe attacked what he considered to be a nest of opponents. By razing kilometers of informal settlements, shops and businesses, he rapidly created tens of thousands of unemployed and hundreds of thousands of homeless across Mbare province. (4) The name given to this operation was “Murambatsvina” a Shona term meaning “Out with the garbage!”, clearly demonstrating the ruling state’s downgrading and marginalization of certain populations (more or less comparing them with waste), involved in an alternative economy. Their very existence is being played out in an alternative history of Zimbabwe.

Somewhat ironically, the artist’s surname Takadiwa, meaning “we have been loved” in Shona, seems to respond to the interior racism of the scornful “Murambatsvina” as a sign of the reintegration of those who were marginalized or literally driven out during the most serious socio-economic crisis of the post-independence period (2006-2008). The cruelty of a government ready to decimate entire sections of its population, found its pretext in the very ability of he latter to develop an alternative economy and an autonomous way of life, with no direct ties to state structures (or desperately needed foreign currency). This developing autonomy is sublimely epitomized by the works of Moffat Takadiwa as spaces of repopulation.

Morad Montazami

1 Nathalie Etoke, Melancholia Africana, Paris, Cygne Press, 2010, p. 30

2 Echos of these psycho-geographical issues, with regard to the informal economy and urban development can by found in the analyses carried out in Kinshasa in Suturing the City. Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds, F. de Boek and S. Baloji, London, Autograph ABP, 2016, p. 130-131.

3 By securing the removal in 2015 of the Rhodes statue from the forecourt of the University of Cape Town (South Africa), the Rhodes Must Fall collective initiated a major wave of cultural decolonization, particularly in the academic and museum sectors. Through its influence on the works of artists, writers and ordinary citizens, themselves born of this historical decolonization, this movement, seeking to “update” memories and the monuments that embody them, has already taken giant steps towards a change in mentalities. At present, the Rhodes Must Fall collective is waiting on the decision of Oriel College of Oxford University, which is also planning to take down its statue of Cecil Rhodes (a decision process that appears to be more laborious and tricky than at the University of Cape Town in 2015.)

4 See: https://www.nytimes.com/2005/06/11/world/africa/zimbabwes-cleanup-takes-a-vast-human-toll.html

Morad Montazami is an art historian, publisher and exhibition curator. After spending several years at the Tate Modern in London (UK) as Middle East and North African arts curator (2014-2019), he now directs the Zamân Books and Curating platform, which is dedicated to the study of Arab, African and Asian modernity. He was responsible for the exhibitions Bagdad Mon Amour, Institut des Cultures d’Islam, Paris (FR), 2018 and New Waves: Mohamed Melehi and the Casablanca Art School Archives, The Mosaic Rooms, London/MACCAL (UK), Marrakesh/Alsekal Arts Foundation, Dubai (AE), 2019-2020. He is a member of the collective Globalization, Art et Prospective, attached to INHA, Paris (FR) and regularly publishes in catalogs, collective works and various periodicals.